Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

6 min read

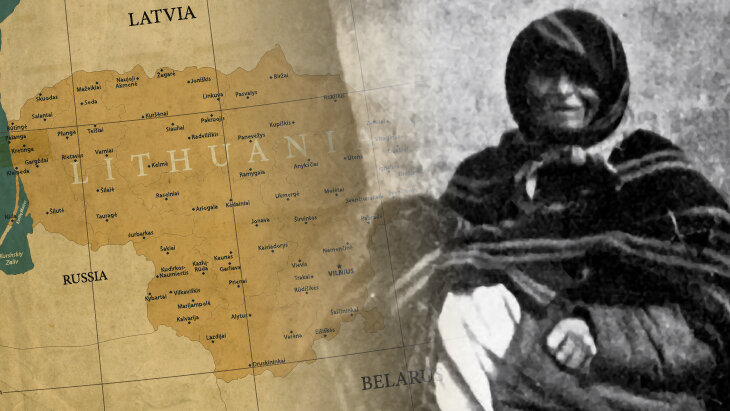

One of the largest single expulsions of Jews since Roman times occurred in May, 1915.

The First World War was a time of tragedy, trial and tribulation for world Jewry. In May 1915, during the holiday of Shavuot, one of the largest single expulsions of Jews since Roman times was executed. Over 200,000 Jews in Lithuania and Courland (Latvia) were abruptly forced from their homes into dire circumstances.

With the advance of the German army on the Eastern front in the spring of 1915, retreating Russian forces vented their fury against the Jews and blamed them for their defeats. They leveled spurious accusations of treason and spying for the enemy and sought to prevent contact between Jews and German forces by expelling Jews near the war front. Throughout the provinces of Poland multitudes of Jews were expelled. Many also fled from their homes in fear of pogroms.

By late March, German forces approached Lithuania as Russian forces continued their retreat. On May 11, at the town of Kuzhi, the local Jews were accused of hiding German troops in their homes prior to a German attack in that town. Proofs were brought following an investigation by three members of the Duma (Russian Parliament) that the charges were absurd and false. But the accusations had already spread throughout Russia via newspaper reports and became another pretext to persecute Russian Jewry. The mass expulsion from Lithuania soon commenced.

While preparing for the upcoming Shavuot holiday, notices appeared calling for the Jews living in areas closer to the war front to leave their homes over the next two days. Many notices gave them 24 hours or less.

Lithuanian Jewry, whose legacy goes back of hundreds of years, made a hasty exit in just a few days.

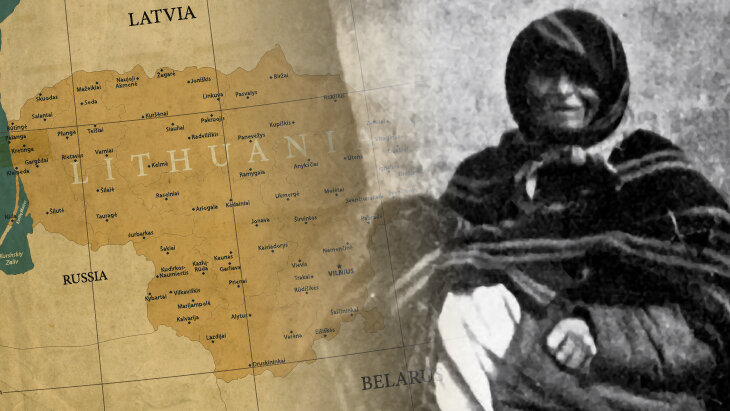

Ordered to move eastward, Lithuanian Jewry, whose legacy goes back of hundreds of years, made a hasty exit in just a few days. Even the sick and the infirmed were included in the decree. Those who did not comply faced execution.

With the evening of Shavuot, May 18th, approaching, multitudes of Jews headed out into an environment of unknown perils in a desperate search for refuge. Out in the open fields and roads facing numerous dangers, they recited Kiddush over wine and organized minyanim (quorums) for the holiday prayers.

In Courland, Jews faced a similar fate, although the expulsion was enforced a day or two later.

As the exodus commenced from the town of Keidan, according to one eye-witness, “People bid farewell. On their last night in Keidan, they slept on their bundles as cannon fire shook the walls or their homes.” Thirty carts filled with men, women, and children headed towards the city of Homel. From there they would be forced further East.1

A street in the Jewish Quarter of Vilna. Yad Vashem Photo Archive

A street in the Jewish Quarter of Vilna. Yad Vashem Photo Archive

A Jewish military physician watched as hundreds of Jews of the town of Keidan hastily gathered their belongings. In shock and despair, he asked them why they were being expelled. They responded, “Because we are Jews!” With tears in his eyes he replied. “I risk my head for them and they exile my brothers.” Such was the case for so many Russian Jews who valiantly served in the Tsar’s army while their families faced persecution. 2

The historian, Simon Dubnow, presented numerous accounts of the expulsion in the 1918 edition of the Russian Jewish journal Yevreiskaya Starina. In the town of Ponevezh, “There was real pandemonium. Household goods, hurriedly bundled into bags, tablecloths, baskets, trunks - everything was jumbled together. Children lost their parents, who frantically raced around, searching for them; the wails of children, the groans of the sick, wailing, shouting. They had brought the residents of the alms-house. Blind old men with shaking hands, stricken by paralysis, old women with knapsacks... The fatally ill were laid on pitiful rags at the very roadbed.” The Ponevezh alms-house had been home to 43 elderly people. The youngest of them was 67, the oldest 97. 3

Jews at a railway station, 1915

Jews at a railway station, 1915

Jewish communities aided refugees arriving at their towns, giving food, lodging, and sometimes employment. The Yekapo organization, an abbreviation for the “Jewish Community Relief War Victims” would wait at train stations and other locations to offer aid. Sometimes, the very communities assisting the refugees would soon become refugees themselves, forced out by the same decree.

Some exiles went to Vilna, where there was no expulsion. One rabbi described the reaction of the Vilna community to their arrival, "It was the first day of Shavuot and the Jews of Vilna went to synagogue not knowing that the first train with all those expelled had already arrived. Notwithstanding that it was a holy day, meeting places where quickly organized and each Jewish family of Vilna was required to bring something edible… In the course of two hours, thousands of kilograms of bread, sugar, meat, cheese, eggs, boiled meat and herring were collected."4

The expulsion decree did not last. Soon after, commander in chief of the Russian armies, Nikolai Nikolayevich, told his commanders to stop the mass expulsions of Jews. The local economy had been damaged and the image of Russia had suffered as well. He proposed that Jews should be expelled only from one specific place at a time in “unusual cases”. 5

Jewish life in Russia would never be the same.

The long-term impact of the expulsion was significant. With the dismantling of Jewish communities, the religious life of Russian Jewry markedly declined. The religious institutions that are the lifeline of the community – the cheder (Jewish school), the mikveh, the synagogue and the yeshiva – were diminished by the massive sudden dislodging of Lithuanian Jewry. Jewish life in Russia would never be the same.

Jewish burial near the Galician theater of war, 1915 (Public domain)

Jewish burial near the Galician theater of war, 1915 (Public domain)

Due to the severity of the expulsions, the Pale Settlement which forcibly confined Russia’s Jews since the end of the 18th century officially ended with a decree in August 1915, allowing Jews to move to Eastern Russia. The intention was not to free the Jews from the confinement of the Pale but to keep them out of the proximity of the war front due to irrational suspicions of Jewish disloyalty.

In one small vacant Lithuanian synagogue on the first day of Shavuot, Jewish refugees had gathered to pray. According to an eye-witness account of the expulsion, as recorded in the book, Milchomo Shtoib (War Dust), the Rabbi of the town of Shavel, the eminent Rabi Meir Atlas, arose and stood before the shocked and traumatized group and offered the following consoling words: “Children, it will pass. Thousands of years of pain and suffering have already passed. This is the will of God. And now, let us say Hallel (the holiday prayer offering praises to God).”6

May the memories of the righteous who endured and suffered on Shavuot 1915 be for a blessing.

My late grandmother used to cry bitterly about the expultion at a young age.she told about reaching a place that was extemely cold that your hand stuck to any metal.

I heard that the scattering of the community saved many from the murders in the holocast