While evaluating our BMI and considering the pros and cons of Keto or Paleo, it’s highly unlikely we ever stopped to think about the daily calorie count of women in the Bible. For Dr. Tova Dickstein, an expert on ancient and biblical foods, this is not only a subject she focuses on, but is very precise about.

A woman living in Ancient Israel ate around 1600 calories a day, Dickstein informs me during our interview at Neot Kedumim, the biblical nature reserve where she curates the botanical garden and oversees educational programs.

But how is it possible to be so sure of the quantity eaten by women 3500 years ago? In this case, Dickstein reveals, the Mishna (the Jewish oral law) is a treasure trove of information. In the rabbinical text, a reference is made to a discussion held by the family affairs committee of the Sanhedrin (the ancient Jerusalem supreme court of law) in which an exact list is given of the amount of food a man, who has deserted his wife, must provide for her over a six day week.

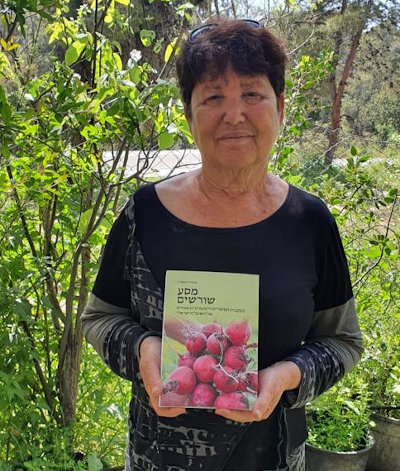

In Dickstein’s recently published book, Masa Shorashim (Roots Journey, in Hebrew only), based on her 20 year, personal journey as a food archaeologist, she details this list: “Alimony was set at no less than two kav of wheat or four kav of barley a week for her sustenance…half a kav of legumes, and half a log of oil, and a kav of dried figs or the weight of a maneh of fig cakes (Mishnah, Ketuboth 5, 8).”

The biblical diet turns out to be healthy and balanced. “You could see it as restrictive in that it only contains four products in all, wheat, lentils, oil and figs,” Dickstein says, “but on second thought, it appears that our ancestors, who knew nothing about amino acids – the building blocks of protein – still knew that a combination of whole grains with legumes was equivalent in its nutritional value to meat.” Figs, she says contain starch and calcium and with the addition of a few wild herbs that the woman could gather herself, or an egg from chickens she might have raised, this could almost meet her full nutritional needs of about 1,700 calories a day.

They were doing something right, Dickstein says with a smile, “as we can see in mosaic art and murals these women were not overweight. They didn’t even have to go to the gym. They were trim from just grinding the flour, which was almost entirely women’s work. It took an hour to grind one kilogram of flour.”

So how does a food archaeologist understand what exactly the ancient ingredients refer to, how to make them into dishes as close to the original as possible, and then write up recipes we can actually follow in our 21st century kitchens? For this, Dickstein can be considered not only an academic, but part detective and innovative chef as well. She modestly says it all started with her love of cooking and knowledge of Aramaic and the Jewish sources. It didn’t always go smoothly and she would often have to experiment over and over until she was able to achieve her aim. One of her first discoveries was understanding Ashishim, a dish written about in the Jerusalem Talmud and which she believes was eaten in King Solomon’s court and referred to in the Song of Songs. The first time she tried to make this sweet lentil and sesame seed dish it came out a charred sticky mess. In the end she realized that the lentils had to be mashed and turned into a pancake form. "It's a different taste from what we are used to. By tasting the food they ate and smelling the cooking aromas they smelt we can connect to the past". Get the recipe for Ashishim here.

Additional ways of research are more traditional: archaeological finds such as the remains of bones and plants are important elements to gaining a complete picture of what was eaten from the time of Abraham to the Talmudic period. “Some parts of the plant, such as rinds, seeds and even pollen, can be preserved under certain conditions for hundreds of thousands of years. For example, we are able to know today what people, who lived in the area of the Bnot Ya’akov Bridge in the Jordan Valley, ate as far back as 780,000 years ago. Luckily when the water level declined in that area, thousands of remnants of food were uncovered.”

These finds reveal that carp was a favorite fish, as well as tilapia in prehistoric times. Wild plants were also important to their diet and 9,000 remains of plants, bulbs, seeds and roots were found. Among them were almonds, acorns, pistachios, grapes, figs, olives, barley and an aquatic plant such as water chestnuts.

Dickstein points out that by visiting traditional kitchens of Israelis (including Samaritans, Yemenites and Ethiopians), Palestinians and the neighboring countries of Jordan, Crete and Turkey she has managed to collect a wealth of information first hand by observing food preparation methods and recipes passed down from generation to generation.

Research undertaken in Crete led her to debunking the myth of Ezekiel bread, touted by many as the healthiest bread as it is gluten free and easy going on the digestive tract. Dickstein says before dealing with the subject of Ezekiel bread, it has to be emphasized that bread in its biblical sense is not what we think it is. “Bread is not a baked item at all, but a generic term for all food, for livelihood and for life itself. And although the dish Ezekiel ate was called bread, a Bible story notes that Ezekiel ate this dish with bread, so it is obvious one does not eat bread with bread. Ezekiel bread is actually a stew.”

In Crete, Dickstein discovered palikaria, a ritual food with components identical to Ezekiel’s ‘bread’ that is still eaten today. “The meaning of the Greek name means ‘mixture’ and the dish combines seeds and wheat, barley, beans, lentils, and even millet just like that of the original Ezekiel bread. We read that it was “all added to one vessel” so it is clear it was a stew.”

Whether eating grapes and olives, drinking wine or tallying a calorie count to 1600 a day, without knowing it, “we are going back to our roots without even noticing,” says Dickstein. Her hard work will hopefully change that and connect us to our earliest culinary roots.