How Anti-Zionist Cancel Culture Silenced an Israeli Comedian

How Anti-Zionist Cancel Culture Silenced an Israeli Comedian

20 min read

An overview of the history, etymology, aspirations, and roots of the Zionist movement, as well as its many detractors.

Zionism is the idea that Jewish people should live in Israel. It’s an idea that’s integral to Jewish belief and is first mentioned in the Torah, in the book of Genesis 12:7, “God appeared to Abram and said, ‘I will give this land to you and your offspring,’” with more specific boundaries mentioned in Genesis 15:18, “On that day, God made a covenant with Abram, saying, ‘To your descendants I have given this land, from the Egyptian River as far as the great river, the Euphrates…’”1

The Jewish people lived in Israel throughout the biblical period, and numerous archeological finds confirm that fact, with the oldest mention of the name, “Israel,” being the Merneptah Stele, attributed to the Egyptian pharaoh, Merneptah, who ruled from 1213-1203 BCE. The Jewish people were also considered the land’s indigenous population during the classical era. At the time, the land was called “Judea,” and the names, “Jewish,” and “Jew,” attest to that association until today.

It was during the classical era—a period when Israel’s Jewish population was, at times, sovereign, and at others, subjected to Greek and then Roman colonial rule—that the by-then long-held Zionist ideals, like the centrality of the land to Jewish observance, and the importance of living in the land, were incorporated into the daily liturgy, along with a number of fast days, and other acts of remembrance.

Throughout the long Jewish exile and diaspora, a period that started in the first centuries of the common era, Jewish people have prayed, dreamed, and longed to return to the land of Israel. Some Jews did. Some Jews never left—Israel boasts an almost continuous Jewish presence since Roman times, which ebbed and flowed depending on the geopolitical realities of the age—even after new centers of Jewish life and scholarship were established elsewhere.

The modern Zionist movement—particularly its nationalistic, political, and cultural focus—started in the late 19th century. It played a leading role in the push for Israeli independence, which was declared in 1948 after 28 years as a British colonial project, following centuries as a corrupt, dysfunctional Ottoman backwater.

The word, Zion (ציון), is first mentioned in the book of Samuel II, 5:7, in reference to King David’s conquest of Jerusalem, “And David conquered the Fortress of Zion, which is the City of David.” The City of David, or Zion, is located to the south of the Temple Mount (Mount Moriah, which today is the location of the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque), just outside the walls of the modern-day Old City of Jerusalem (and the site of an extensive, and mind-blowing, archeological dig), and not to be confused with what is today called “Mount Zion,” which is the hill just outside the Old City’s Zion Gate.

But Zion is more than just a physical location. It is mentioned numerous times throughout the books of the Bible—particularly in the books of Isaiah and Psalms—in a poetic, or aspirational sense, and in reference to the Torah and the Temple as the focal points of Jewish spiritual life, like it says in Isaiah 2:3, “Many people will go and say, ‘Come, let us go up to the Mount of God, to the Temple of the God of Jacob, that He may teach us His ways and we may walk in His paths.’ For the Torah shall go forth from Zion, and the word of God from Jerusalem.”

Jews Praying at Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, by Johann Martin Bernatz (Ottoman Archives, 1868)

Jews Praying at Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, by Johann Martin Bernatz (Ottoman Archives, 1868)

In other words, Zion is a concept that entwines the highest ideals of Jewish belief together with Jerusalem and the land of Israel. It’s also mentioned many times in the daily Jewish prayer service, which reinforces that connection. That said, in 1880, when, in response to pogroms in Russia, a number of Jewish activists dedicated to promoting Jewish immigration to what would become the state of Israel decided to join forces, they called their new group “Lovers of Zion” (Hovevei Zion/חובבי ציון). It was the intuitive choice.

The term “Zionism” was coined in 1890 by Nathan Birnbaum,2 who was a former student activist—he co-founded the Vienna-based Jewish student organization, Kadimah, in 1883—and published, Self Emancipation! (Selbstemanzipation!), in which he wrote many of the articles (under different names), and also came up with other iterations of the term like “Zionist” and “political Zionism.”

The Zionist movement, depending on who you asked, was either a political, cultural, religious, or national movement—or, most likely, a combination of those ideals—that captured the popular imagination with the publication of Theodor Herzl’s, the Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), in 1896. It became a political force the following year with the First Zionist Congress, organized by Herzl, in Basel, Switzerland.

The modern Zionist movement is not monolithic—different Zionist groups emphasize different issues they deem important, be they national, religious, or otherwise—but their common denominator is the importance and centrality of living in Israel.

The roots of Zionism as a modern nationalist movement were first outlined in the pamphlet, Auto-Emancipation (Selbstemanzipation), published by Polish-born physician and activist, Leon Pinsker, in 1882. Pinsker had advocated for enlightenment values and equal rights for much of his life (he was born in 1821), but in the 1880s, after successive waves of violent anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia, became convinced that antisemitism was too great a force to overcome, and that Jewish self-rule was the only alternative. That idea caught on, and became an animating Zionist ideal.

The revival of Hebrew as a spoken language was another important aspect of early Zionism. Throughout the centuries, Hebrew had been kept alive as a language of scholarship and prayer, but few people spoke it, and its pronunciation varied depending on the community. Eliezer Ben Yehuda, a Lithuanian-born linguist and journalist, led the effort to standardize pronunciation, started a group that created new Hebrew terms for modern words, and began work on a Hebrew-language dictionary that his wife completed and published after his death.

Other important streams in Zionist thought include religious Zionism, which emphasizes the theological basis for the Jewish return to Israel; cultural Zionism, which sees Israel as the spiritual center of a global Jewish cultural revival; and various socialist movements that led to the establishment of communal settlements, or kibbutzim.

As mentioned above, the Jewish people lived in Israel in biblical times. After years of conquest and strife, which included the destruction of Jerusalem—as described in the biblical book of Kings—many of those Jews were resettled in Babylon, in what is today Iraq. Babylon itself fell to the Persian Empire about 50 years later, and soon, some Jews made their way back to Israel. It was also around this time that the names “Jewish” and “Jew,” meaning “the people from the land of Judea”—the area that is today Israel—were first applied to the Jewish people as a whole.3

That first return to Israel, led by Ezra—and as described in the book of Ezra, chapter 8—is known as the “Return to Zion,” which is taken from Psalms 126, “When God returns the returners to Zion (שיבת ציון), we will be like dreamers.”

That idea, that the Jewish people are not a homeless religious community, but a nation with a specific, and particular homeland, is integral to Jewish identity and belief. It is a defining characteristic of Jewish spiritual life, and, in addition to a continuous Jewish presence in Israel since Roman times, many diaspora Jews made the effort to return and establish communities in Israel over the years, with varying degrees of success.

Contrary to the simplistic way Jewish history is often taught, the Jewish people were not exiled from Israel following the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple in the year 70. Jewish life continued in Israel for centuries after that event, although most of that era’s leaders and scholars were based in northern Israel, in the Galilee. The last major revolt against Roman rule was the Bar Kochba Rebellion (in the years 132-136), which the Romans crushed. As a result, and in an effort to show Roman dominance, the Romans renamed Judea “Syria Palestina,” and that name was used, with modifications, throughout the remainder of Roman rule (the emperor, Hadrian, had already changed Jerusalem’s name to “Aelia Capitolina” in around the year 130).

Despite those hardships, Jewish intellectual life in Israel thrived in the first centuries of the common era. The Mishna, the six-volume foundational work of Jewish law, was compiled and redacted in the Galilee in around the year 200. The first iteration of the Talmud, the Jerusalem Talmud, was compiled in the year 350, in that same region. Many other important rabbinical texts were composed in Israel in that period as well. However, life under the Romans was difficult, and by the fifth century the center of gravity of Jewish life had shifted to what is today Iraq, with major academies in cities along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Although, even with those changes, major scholars still lived in the Galilee and Golan, and, as is often noted in the Babylonian Talmud (compiled and redacted in the fifth century), visited the academies in Iraq, and brought them news of life—as well as the opinions of the leading scholars—in Israel.

Next Year in Jerusalem, from the Barcelona Haggadah

Next Year in Jerusalem, from the Barcelona Haggadah

It was in these works as well that many of the tools designed to remember the land of Israel were encoded into Jewish law. Some of these include: four annual fast days, the most important being in the summer, on the ninth of the Hebrew month of Av; daily prayers for the rebuilding of Jerusalem and an ingathering of the exiles; ending every Passover Seder with the call, “Next year in Jerusalem;” breaking a glass at the end of every wedding as remembrance of Jerusalem; and many others.

Jews persisted in their connection to Israel, not only in prayer, but with their physical presence as well. They were in the land during the seventh century Arab conquest, which included the lifting of a ban against Jews entering Jerusalem. They were slaughtered when the Christian Crusader armies captured Jerusalem in 1099. They were living in Israel in the 13th century, including in coastal cities like Acco, when the Spanish sage, Nachmonides—after being exiled from Spain—arrived in 1267. They fled to Israel in the late 15th century, when it was then under Ottoman rule, following the Spanish Inquisition and expulsion. It was even in Israel, in Gaza, in the mid-17th century, where the false messianic movement led by Shabbatai Tzvi began to pick up steam.

Israel is a focus of Jewish life, and Jews have always made an effort to live there.

For many, the modern return to Zion starts in 1777 when Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, an early Hasidic leader and disciple of the Maggid of Mezritch—himself a close student of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of the Hasidic movement—emigrated to Israel, along with 300 followers, and settled in the northern city of Tiberius. In 1812, a group of about 500 followers of the great Lithuanian sage, known as the Vilna Gaon (the genius of Vilna), settled (eventually, after a few fits and starts) in Jerusalem, and laid the foundations for a number of Jewish legal practices that are still followed in Israel today.

But it was the assassination of Tzar Alexander II in Russia in 1881 that led to a significant uptick in anti-Jewish violence and riots, and a mass exodus of Russian Jewry—with an estimated 2.5 million Jews immigrating to the United States—which was also the impetus behind the modern Zionist movement, or the idea that only Jewish self-rule could provide an escape from the seemingly never-ending cycle of antisemitic violence.

Some early Zionist thinkers and leaders from that period include Leon Pinsker, who was onboard with the official charter of Hovevei Zion in 1884; Nathan Birnbaum, who coined the term Zionism in 1890; Asher Hersch Ginsberg, who wrote under the pseudonym, Ahad Ha’am (one of the people), and who was an important intellectual leader; Eliezer Ben Yehuda, considered the father of modern Hebrew; important philanthropists like Baron Edmond James de Rothschild and Sir Moses Montefiore; and many others. However, the watershed moment for the Zionist cause was the publication of Theodor Herzl’s the Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), in 1896, which, more than anything else, galvanized popular support for a Jewish state.

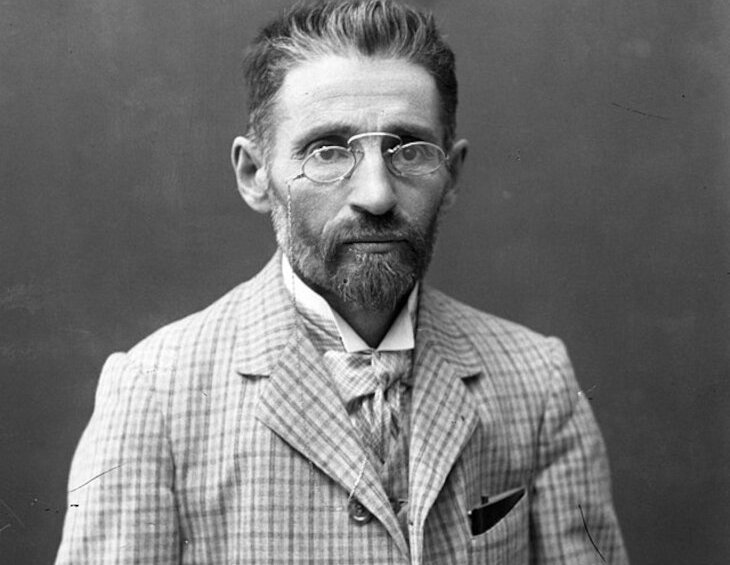

Eliezer Ben Yehuda

Eliezer Ben Yehuda

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were also a time of significant Jewish immigration to Israel. Despite hardships and Ottoman reluctance, successive waves of Jews made their way to the land. The First Aliyah (as in “going up,” or “ascent”) brought about 30,000 Jews to Israel between 1882 and 1891. The next wave, called the Second Aliyah, which followed a brutal pogrom in Kishinev (in modern Moldova) in 1903, brought another 40,000 Jews to Israel between 1904 and 1914. Additional waves followed—albeit curtailed at times by both Ottoman and British authorities—through the founding of the state in 1948.

Jewish immigration to Israel created a conundrum for Arab and Ottoman landowners, many of whom were absentee. The new Jewish settlers bought the land they settled, which the local land holders couldn’t resist selling at exorbitant prices (and the Jews paid those prices). Yet, simultaneously, couldn’t tolerate the idea of dhimmi Jews gaining the perceived upper hand. That problem was compounded when local fellahin, or Arab peasants, flocked to the areas of Jewish settlement. Those Arabs came for new jobs, higher wages, and an end to the cycle of poverty, indentured servitude, corruption, and abuse that absentee Ottoman landlords inflicted upon the region for centuries. Unfortunately, those Arab workers—many of whom were new immigrants to the region themselves—also harbored similar prejudices against what they considered dhimmi Jews.4

That paradox, which both depended upon Jewish immigration (and concomitant Jewish money and jobs), yet also despised Jewish immigration, in many ways set the stage for more than a century of subsequent bloodshed and violence.

Theodor Herzl was not the first modern Zionist, but it was the publication of his book, the Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), in 1896 that set the Jewish world ablaze. Herzl was raised as an assimilated Jew and considered enlightenment values the solution to centuries of animosity against Jews. But as a reporter covering the infamous Dreyfus Affair in 1894—the trial against a French Jewish officer accused of being a spy, which turned out to be false—was shocked to hear calls of “Death to the Jews” in what he considered modern, civilized, enlightened France. That turned him into an activist, and ardent Zionist.

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl

Publishing the Jewish State was just the beginning. Herzl was well-connected, well-educated, wealthy, charismatic, and a gifted leader and organizer. He organized the First Zionist Congress in 1897 in Basel, Switzerland, which brought together many of the leading Zionist thinkers, and resulted in an official Zionist platform, the founding of the Zionist Organization, starting a process that led to the establishment various Zionist financial institutions (including a bank and the Jewish National Fund), the creation of Israel’s flag, and more. He also met with world leaders, visited Israel, traveled and gave speeches, and presided over additional Zionist gatherings before dying an early death in 1904 at the age of 44.

Herzl wrote in his diary following the First Zionist Congress, “At Basel I founded the Jewish State. Perhaps in five years but certainly in 50 everyone will know it.” (He was off by nine months).

Following Herzl’s death, Chaim Weizmann, a Russian-born chemist, became the movement’s next leader. In 1917, at the height of the First World War, he convinced the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, to promise support for a Jewish National Home following the inevitable collapse of the Ottoman Empire after the war. That support became known as the Balfour Declaration, which was formally approved by the League of Nations in 1922. The original territory designated as the “future home for the Jewish people” included all of modern-day Israel and Jordan, but in 1921, the British created Transjordan out of about 77 percent of the territory, or all of the land east of the Jordan River. That land was gifted to the Hashemite dynasty, an absolute monarchy that still rules the area today.

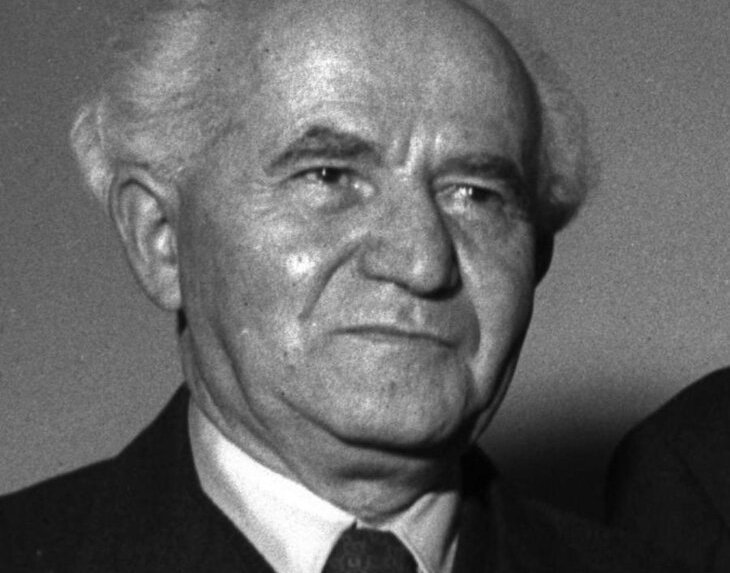

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion

On the ground in Israel, the most significant Zionist leader was David Ben-Gurion. Originally from Poland, Ben-Gurion moved to Israel in 1906 where he worked as a farmer and socialist activist. The Turkish exiled him, and he spent a number of years in New York. He returned to Israel in 1919, where he was a leader of the Labor Zionist movement. In 1935, he took over as head of the Jewish Agency, which was the leading Zionist organization that the British recognized as representing Jewish interests. In 1948, he became Israel’s first Prime Minister.

The original anti-Zionists were religious Jews who lived in the Jerusalem area under Ottoman rule. They built some of the first neighborhoods outside Jerusalem’s Old City, including Meah Shearim, where some still live today. Calling themselves the Neturei Karta (the Guardians of the Gates), they rejected the secular Zionists immigrating to Israel, and claimed that the establishment of a Jewish state was a feature of the messianic era, which was not yet underway. Prior to World War II, they had a lot of support throughout the religious Jewish world. However, with the establishment of the state in 1948, much of the Haredi world changed its views, and today participates in Israeli society, votes in elections, and sends representatives to the Knesset. The last holdouts, who still use the name, Neturei Karta, are considered an extremist fringe group, and not representative of the religious Jewish world.

Modern, Western anti-Zionism is a left leaning ideology that attempts to obfuscate its antisemitism by using language that emphasizes Israel and Zionism in place of Judaism or Jews. Anti-Zionism is an Orwellian theory where Jews are “Nazis,” and Arabs are “Jews.” Anti-Zionists present their positions as critical of Israeli government policies, but in reality they demonize Jews—regardless of where those Jews live or what they believe—and fall back on age-old tropes, libels, and accusations; condone vandalism and violence; rationalize terrorist attacks, hostage taking, and downplay evidence of rape and other horrors; and pressure businesses, universities, entertainers, and governments to support a Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction (BDS) campaign against Israel. Those types of wild, often unhinged accusations cross a line. They’re not valid, reasonable criticism of Israeli government policies, but antisemitism.

Zionism is the belief that Jewish people should live in Israel. For millennia, and especially since Roman times, Jews have settled in Israel, purchased land, built communities, maintained a small but vibrant presence, and struggled to keep that dream alive. In the modern era, Jews organized, and leveraged significant financial and political capital to establish an independent Jewish state in Israel. That effort, which led to the founding of the state of Israel in 1948, brought significant resources, innovation, investment, and advancement to the region. It made Israel a first world nation, and improved the lot of its inhabitants, including the many Arabs who flocked to the region in the early days of the Zionist project, and their myriad descendents.

In other words, despite much opposition, and many bumps along the way, Zionism is good.

What’s bad is the reaction to Zionism. The intolerance of Jewish sovereignty, the inability to accept dhimmi Jews as equals or fully human, the mischaracterizations and misinformation manufactured against Israel, the demonization of Jews as illegitimate colonial occupiers, as well as the lazy antisemitic tropes hurled at Jews, Israel, and the Zionist project, are the actual problem.

More than that, those libels only bolster the case for the necessity of an independent Jewish state, and strengthen Jewish resolve.

Zionism is the idea that Jewish people should live in Israel. It’s an idea that’s as old as Judaism, and is first mentioned in the book of Genesis 12:7 when God promised the land to Abraham and his descendants. Archeological finds confirm Jews were living in Israel in the 13th century BCE, and in Roman times, Jews were considered the land’s ancient, indigenous people. Over the centuries, the center of gravity of Jewish life has shifted to other communities, but Jews have always maintained a presence in Israel, and today it is again the focal point of Jewish life, with about half the world’s Jews living in the modern state of Israel. The modern Zionist movement began in the late 1800s, with the First Zionist Congress being held in 1897, and a sovereign Jewish state being declared in Israel in 1948. In recent times, antisemites have attempted to use Zionism as a way to obfuscate their hatred against Jews, yet despite the bad press and hardships, Israel, along with the Zionist project, has been a net good for the world.

Zionism is the belief that Jewish people should live in Israel, which is a foundational Jewish idea. The Torah, the central Jewish text, contains 613 commandments, 342 of which can only be performed in the land of Israel (as they relate to agriculture, agricultural cycles, establishing the calendar, and the various services that are only performed in the Temple in Jerusalem). Indeed, the names “Jewish” and “Jews” derive from the name “Judea,” which was the name Israel was called in late biblical times and throughout the classical era, and indicates the centrality of the land to Jewish worship and belief. Judaism is not a universal religious system, but a national one that’s linked to a specific geographical location.

Although the word “Zion” refers to a specific location in the Jerusalem area, its use—particularly in the books of Isaiah and Psalms—is aspirational and poetic, and entwines the highest ideals of Jewish belief together with Jerusalem and the land of Israel. In modern usage, it refers to the belief—be it political, religious, cultural, or otherwise—that Jewish people should live in Israel.

The modern Zionist movement began in the late 1800s, but became a political force following the publication of Theodor Herzl’s the Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), in 1896, and the First Zionist Congress a year later.

Featured Art Work Above, Kidron Wind, by Yoram Raanan. Visit his site at https://www.yoramraanan.com/

It was well past time that an in-gathering of a significant number of the scattered chosen people returned and gathered in the land given to them by God for them to dwell within. The presence of a worldwide malignant spirit which hated them for nothing other than their election being so strong and ubiquitous makes it seem to be simple wisdom now.

Structuring the modern homeland according to the pattern of most other nations steeped in biblical ethics and morality was the only way to go for numerous reasons.

Experiencing internal political divisions, variants of the methods of governance comes with the dignity of the individual and the practice of rule by elected representatives.

For an actual eye opening and precise definition and history of Zionism through the words of actual Zionists, look up R' Ashi Stenge who is in the middle of an incredible (and accurate) series on the topic.

"However, with the establishment of the state in 1948, much of the Haredi world changed its views, and today participates in Israeli society, votes in elections, and sends representatives to the Knesset."

According to this faulty logic, one cannot be opposed to Zionism and vote in Israeli elections - so what about the Arabs who live here and vote and send representatives to the Knesset - are they also pro-Zionist?

I looked to me like an observation of current affairs in clarifying unfolding actual events

What a great piece!

My name is Devorah Fastag and I have written a book on women's status in Judaism called The Moon's Lost Light, which slightly discusses Zionism, as the two are connected. (To find out how, read the book.) I also wrote a booklet on Zionism called Whatever Happened to the Aschalta Degeula. I would like to send it to you via email. Is there a way to do so? Would you read it?

"[Leon Pinsker] ...became convinced that antisemitism was too great a force to overcome..."

No force is too great with the help of HaShem.

Without the Zionist movement, it’s very possible that Israel would not exist today. Zionism is good, anyway you look at it.

at the end , everything that has happened or will happen in the future, is will of G’d.

I enjoyed reading very well documented history of our people.

thank you for taking your time to educate us.

may G’d bless Israel!!!

The article states: "...despite much opposition, and many bumps along the way, Zionism is good."

You'll likely cancel this comment but I'll post it anyway: Zionism is good to the extent that it aligns with Torah-based Judaism. To the extent that it doesn't align with Torah-based Judaism, Zionism is bad.

very good piece, very well-researched and well written. However, the author and readers should realize and understand and research further that modern-day Jewish anti-Zionism is not just Neturei Karta. You can start with the book The Empty Wagon by Rabbi Yaakov Shapiro

Please explain further. In simple layman terms.