Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

10 min read

Though Israel and the United States don’t always see eye to eye, America remains Israel’s greatest ally. For that, we can thank two unlikely heroes: Rabbi Isaac Leeser and John Nelson Darby.

It was 1896 and a handful of unlikely people were about to change the course of Jewish history.

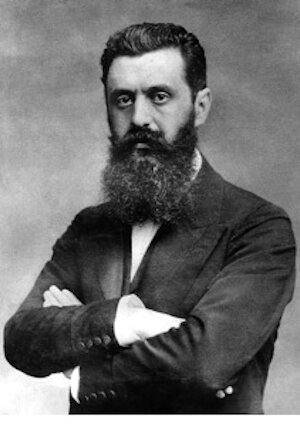

While working as the Paris correspondent for the Austrian newspaper Neue Freie Presse, Theodor Herzl reported on the 1894 trial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army who was accused of selling military secrets to Germany. Covering the trial, Herzl was shocked that French authorities made the Jewish officer a scapegoat for France’s military defeats and was deeply distressed by the antisemitic riots that soon broke out in France.

Cries of “death to the Jews” were heard throughout France, the birthplace of the Enlightenment and the nation that had first opened the doors of Jewish ghettos throughout Europe. If even the French could descend into this kind of brute antisemitism, “what are we to expect from other peoples, which have not even attained the level France attained a hundred years ago?”

Together with renewed antisemitism in his native Vienna, the Dreyfus affair convinced Herzl that the only solution to antisemitism was for the Jewish people to build a state of their own in Israel, their ancient homeland. Within weeks of witnessing the antisemitic Parisian mobs, he feverishly wrote a 65-page pamphlet, The Jewish State (Der Judenstaat), and threw himself into his newfound mission to secure a charter for a Jewish State in the land of Israel - a mission that would soon launch the modern Zionist movement.

A short time after the publication of his groundbreaking book, Herzl heard a knock at the door of his home in Vienna. Opening the door, he found a non-Jewish man he had never seen before. “Here I am,” said William Hechler.

“That I can see,” said Herzl, “but who are you?”

Hechler explained: “Many years ago I predicted your arrival… now I am going to help you.”

William Hechler would indeed help Theodor Herzl in his quest to establish a Jewish state, far more than Herzl could have imagined. Unbeknownst to Herzl, Hechler was part of a Christian Zionist movement that long predated Herzl’s Zionist awakening. Twelve years earlier, Hechler authored a pamphlet entitled The Restoration of the Jews to Palestine According to the Prophets, in which he predicted the imminent return of the Jews to their homeland. Hechler would go on to play a critical role in the new Zionist movement, using his political connections to arrange a meeting for Herzl with the German Kaiser, a meeting that afforded Herzl and his new movement immediate legitimacy.

Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl

Herzl was the first Jew to successfully launch a political Zionist movement, but he was hardly the first to call for the return of the Jewish people to Zion. More than half a century before Herzl published The Jewish State, there were stirrings of Zionism among both Jews and Christians in unlikely places, preparing the way for Herzl’s Zionist revolution. Proto-Zionist thinkers could even be found thousands of miles away from the major Jewish communities of Europe, in the tiny, backwater Jewish community of the United States of America.

Before the large scale of immigration of German Jews in the mid-1800s, the American Jewish community was almost unimaginably small, with a total population of about 4,000 Jews in 1830. In its early years, the community lacked strong Rabbinic leadership, a problem soon remedied by the arrival of Rabbi Isaac Leeser, 19th century America’s greatest traditional Rabbi.

Rabbi Isaac Leeser

Rabbi Isaac Leeser

Born in Westphalia, Germany in 1806, he immigrated to the United States at the age of 18 with a strong background in both Jewish and secular studies. When an attack on the Jews appeared in the London Quarterly and was then reprinted in American newspapers, Leeser responded with a passionate defense of his people in the pages of the Richmond Whig. His articles soon circulated throughout America’s small Jewish community, quickly establishing his reputation and launching his career as a cantor and Rabbi. Over the next 40 years until his death in 1868, Leeser was a veritable “Jewish renaissance man,” writing, translating and publishing a flood of sermons and theological works while serving as a Rabbi and editor of The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, a monthly periodical devoted to the diffusion of Jewish literature and religion.

Rabbi Leeser argued that a return to the land of our fathers was not merely a messianic dream, but a concrete possibility.

Though Leeser’s pivotal role in the American Jewish community is broadly acknowledged, his surprising advocacy for a Jewish state in the land of Israel has received little attention. As other American Jews focused single mindedly on acclimating into American society, Rabbi Leeser argued that a return to the land of our fathers was not merely a messianic dream, but a concrete possibility. “God redeemed us before from the slavery of Egypt… Why he should not be enabled to do the same deed again is beyond the power of my imagination to ascertain. The unwillingness of the scattered Israelites themselves is the greatest difficulty; but in His good providence, He will devise the means” (Isaac Leeser, Discourses Argumentative and Devotional on the Subject of the Jewish Religion, vol. IX, 120).

The Revolutions of 1848, a series of republican revolts against European monarchies, convinced Leeser that the restoration of a Jewish state in the land of Israel was a real and practical possibility. “If ancient Germany again becomes a nation, if Poland throws off successfully the chains of mighty oppressors, if fair Italy takes a rank as one people… if it is truly said ‘a man may die, but a nation never,’ why should not the patriotic Hebrew also look forward to the time when he may again proudly boast of his own country, of the beneficent sway of his own laws, of the bravery of Judah’s sons, of the virtue of Israel’s daughters? Where is the heart that would not swell with a mighty sensation could he once more see our fair land restored to its former beauty, when the wilderness is to bloom as the rose, and the waste cities shall be built up again and the son of David rule in righteousness among his equals?” (Occident, vol. VI, May 1848).

Rabbi Leeser’s final years coincided with the tense years of the Civil War, which brought a sharp rise in antisemitism in both the north and south and culminated in General Grant’s infamous Order Eleven, banishing Jews from Tennessee. The takeaway, wrote Leeser in one of his last essays, was clear: “There is no hope for Israel’s tranquility save in their own land, and we cannot expect to avoid annoyance and molestation from zealots under any form of alien government” (Discourses, vol. VI, 332). Isaac Leeser understood what Herzl would discover 30 years later: that the Jewish people would never find safety and tranquility without a country of their own.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Leeser’s views were explicitly rejected by most Jews in the late 19th century, who feared that Zionism would endanger their status as loyal American citizens. Isaac Mayer Wise, a prominent Reform Rabbi, was strongly opposed to Zionism, as were almost all Reform Rabbis of the time. Two years after Herzl published The Jewish State, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations proclaimed: “We are unalterably opposed to political Zionism. The Jews are not a nation, but a religious community. Zion was a precious possession of the past, the early home of our faith… As such it is a holy memory, but it is not our hope of the future. America is our Zion…”

Leeser’s views were explicitly rejected by most Jews in the late 19th century, who feared that Zionism would endanger their status as loyal American citizens.

For several decades after his death, Rabbi Leeser’s Zionist views gained little traction in the broader community, yet strengthened those Jews who refused to give up on the Zionist dream. But the tide would soon turn in his favor through the emergence of Herzl’s political Zionist movement and another, even more unlikely development: the rise of Christian Zionism.

If Rabbi Leeser’s emergence as a proto-Zionist in 19th century Philadelphia is surprising, John Nelson Darby’s theological rebellion and evangelism for Christian Zionism is almost inconceivable. Darby was a founding member of the Plymouth Brethren, a group of devout Protestants who, disenchanted from the Anglican church, began meeting for prayer and Bible study in Dublin in 1827. Seriously injured in a horseback riding accident, Darby used his long convalescence to closely study the Bible without any preconceived notions. By the time he was healed, Darby was ready to promote a new theology that would radically alter the way millions of Christians view the Jewish people.

John Nelson Darby

John Nelson Darby

Darby read the Bible literally; when the Bible referred to “Israel” or “the descendants of Abraham,” he understood these references as referring to the literal, biological descendants of Abraham - the Jewish people. Therefore, Darby believed that all the promises God made to the children of Israel in the Hebrew Scriptures would be fulfilled, literally, through the Jews. Just as the prophets predicted, the Jewish people were living as a persecuted minority in exile, scattered all throughout the world. If the punishment of exile was fulfilled through the Jews, Darby reasoned, the promise of return to the land of Israel must also be fulfilled through the Jews! God’s relationship with the Jewish people is eternal: “Israel is always the people of God [and] cannot cease to be the people of God.”

Darby’s simple and rational reading of the Bible was revolutionary. For 1,500 years, most Christians believed in replacement theology, asserting Christians had replaced the Jewish people as the chosen nation. Darby’s new Christian theology, in which both Jews and Christians were destined to play key roles in history, planted the seeds for what would later become a powerful political movement: Christian Zionism.

Though his views were adopted by the Plymouth Brethren, Darby seemed unlikely to make a broader impact in the Christian world. Darby, however, was deeply committed to teaching his theology to others, and made the fateful decision to travel across the ocean and bring his new theology to America.

Beginning in 1862, at the very same time that Isaac Leeser was advocating for a Jewish state, Darby spent seven years in America, developing relationships with influential Evangelicals and preaching his new understanding of God’s divine plan. In the final years of his life, Darby developed a following of talented evangelical preachers who embraced his views on Israel and the Jews, carrying his message farther than he ever imagined possible.

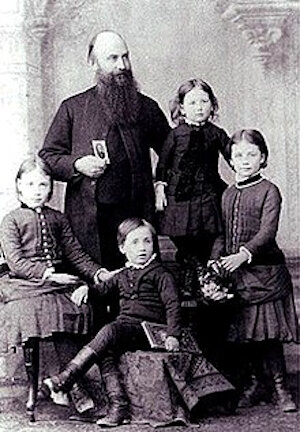

William Hechler and family

William Hechler and family

Over the next 50 years, Darby’s views were popularized by his American student Dwight L. Moody, a preacher who held massive revival campaigns in cities across America. Darby’s views were spread even further by the publication of the Scofield Reference Bible in 1909, which soon became the most popular Bible used by evangelicals in the United States, and which rejected the replacement theology that had once dominated American Christian theology.

Darby’s theology, recognizing the Jews as the rightful heirs of the land of Israel, would later bring William Hechler to Theodor Herzl’s door and would ultimately lead tens of millions of American evangelicals into the Zionist camp, making the United States the most pro-Israel country in the world. Though Israel and the United States don’t always see eye to eye, America remains Israel’s greatest ally. For that, we can thank two unlikely heroes: Rabbi Isaac Leeser and John Nelson Darby.