Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

6 min read

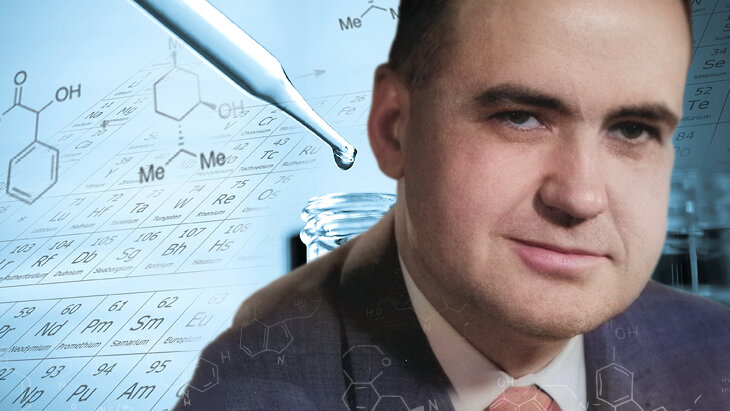

The amazing story of Dr. Maurice Hilleman, the father of modern vaccines.

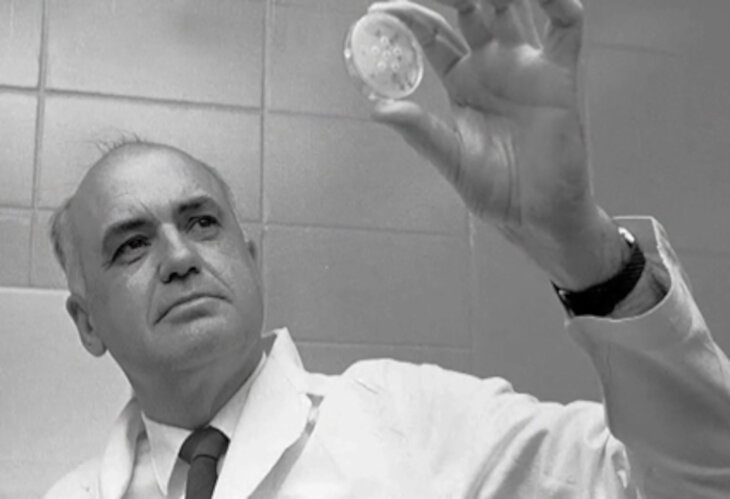

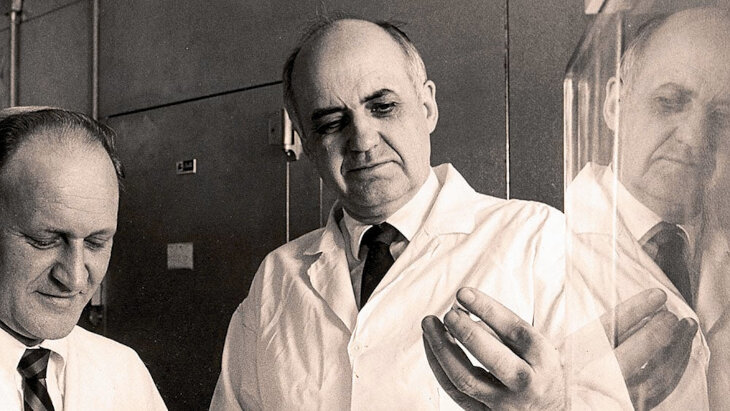

Microbe hunter, pioneering virologist, and the 20th century's leading vaccinologist, Dr. Hilleman is considered the father of modern vaccines. His mission was to save children, which he did in the millions by eradicating common childhood diseases. He was responsible for developing more than 40 vaccines, including those for measles, mumps, hepatitis B, meningitis, pneumonia, Haemophilus influenzae bacteria, and rubella. The measles vaccine alone has prevented approximately one million deaths.

By the end of his career, Dr. Hilleman had prevented pandemic flu, combined the measles-mumps-rubella vaccines (MMR), developed the first vaccine against a type of human cancer. Among other accomplishments, he succeeded in isolating many viruses, including the hepatitis A vaccine. Hilleman worked with many collaborators in academic centers, in industrial management, with which he led his research and development team to produce world-changing achievements. Through his work he has perhaps saved more lives than any other scientist in history.

Unlike Jonas Salk, Hilleman has been largely unknown to the public. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NAID) said Hilleman had “little use for self-credit” and his contributions were “the best kept secret among the lay public. If you look at the whole field of vaccinology, nobody was more influential.”

Hilleman's interest in microbiology and science had its roots in his childhood. Born in 1919, he grew up during the Great Depression on a farm in Miles City, Montana. Tragically, his mother died two days after his birth and Hilleman was raised by his uncle while his father struggled to cope with raising his eight children under harsh circumstances on their family farm.

Young Hilleman in Montana

Young Hilleman in Montana

Hilleman graduated from high school in 1937 in the midst of the Great Depression. As a poor farm boy without prospects or means, he took jobs in local stores and despite working hard he had little opportunity to advance his education. Ultimately, Hilleman applied for, and won, a full scholarship to Montana State University where he graduated first in his class at the age of 21 with a joint degree in chemistry and microbiology. He was offered scholarships at 10 universities and chose the University of Chicago for graduate studies in microbiology where, despite scholarships, he lived under squalid conditions. He received his PhD in 1944 with an award-winning dissertation on chlamydia.

Despite pressure from academics to join them, the tough-minded, impatient genius was committed to creating something useful and converting it to clinical use.

After graduating, Hilleman elected to work in the pharmaceutical industry. He took a position in E.R. Squibb & Sons and immediately started researching vaccine development. He developed a vaccine against Japanese B encephalitis, which was urgently needed to immunize troops at the Pacific front of during World War II.

In 1948, Hilleman joined the Walter Reed Army Medical Center as chief of the Department of Respiratory Diseases, where he was assigned to study respiratory illnesses which had military significance, and to devise a science and strategy for dealing with influenza. Hilleman led the development of the Asian flu vaccine in 1957. The life-threatening flu was spreading across China with reports of 20,000 cases in Hong Kong. Still a microbiologist at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Hilleman suspected this could become a pandemic threat and coined the term Asian flu. He determined that most people lacked antibody protection for this new virus.

He initiated vaccine production by sending virus samples to manufacturers and urging them to develop a vaccine within four months, producing 40 million doses of vaccine and thereby reducing the US epidemic, which caused an estimated 70,000 deaths in the United States. World-wide, from 1957 to 1958, some two million people died from Asian flu.

In 1957, at age 38, Hilleman was recruited by the pharmaceutical company Merck & Company at West Point, Pennsylvania, to lead its virus and vaccination research programs for the next 47 years, continuing to direct the Merck Institute for Vaccinology for another 20 years—after compulsory retirement from Merck Research Labs in 1984 at age 65. It was here, from the 1950s to the 1990s, that Hilleman and his team created more than 40 experimental and licensed human and animal vaccines, including protection against measles, mumps, chickenpox, rubella, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis, pandemic influenza, and chlamydia.

Despite and perhaps because of early personal tragedy and poverty, he developed his passion and followed his extraordinary destiny: saving children.

In 1968, Hilleman was active in developing a vaccine for the Hong Kong influenza pandemic. Because of the continuing threat of annual flu epidemics, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed new pandemic guidelines in 2005 to upgrade pandemic-preparedness plans in cooperation with vaccine manufacturers and national public health agencies, especially addressing the need for quicker development and distribution of influenza vaccines.

During much of his 60-year career he was involved in all pharmaceutical facets from research to the marketplace. Hilleman felt that scientists had a responsibility to provide a return on knowledge gained in the laboratory. He was a fighter who tangled with industry and government bureaucracies. He argued that it was politics, not science, that determined which breakthroughs were brought to the marketplace.

Hilleman's style of working was iconoclastic. In 1963, when his daughter had the classic symptoms of the mumps, he swabbed the back of his daughter's throat, brought it to the lab to culture, and by 1967, there was a vaccine. Today's regulations would preclude that from happening.

After Dr. Hilleman’s retirement from Merck in 1984, he served as a consultant and mentor to those working to stop infectious diseases around the world. In 1988, President Ronald Regan awarded him the National Medal of Science, the highest science award given in the U.S. Hilleman received many other honors, including a special lifetime achievement award from the WHO.

Dr. Hilleman’s work is estimated to save about eight million lives every year.

Colleagues note that Dr. Hilleman was always more concerned with preventing disease than being recognized for his efforts. Many people are unfamiliar with Dr. Hilleman’s name, despite the fact that his work has directly impacted their lives. His work is estimated to save about eight million lives every year.

Despite and perhaps because of early personal tragedy and poverty, he developed his passion and followed his extraordinary destiny: saving children.

Dr. Hilleman died from cancer at 85 in 2005. The next time your doctor gives your child a vaccine to protect him from mumps or measles, remember the name Dr. Maurice Hilleman.

Next week we take an up-close look at Dr. Samuel Katz, an Albert B. Sabin Gold Medal winner and world-renowned advocate of life-saving vaccines.