Raise a Glass to Freedom

Raise a Glass to Freedom

Jewish Geography

Jewish Geography

10 min read

An ancient Jewish community that survived all odds and came home.

The history of the Jews in Yemen spans millennia, encompassing many challenging and prosperous periods. Read on to explore and unravel the captivating narrative of Yemenite Jews, tracing their journey through time, and learn about an ancient Jewish community that survived all odds and came home.

A lone Jewish person remains in Yemen, down from seven in February, according to a new United Nations report about the treatment of religious minorities in conflict zones. (Gabby Deutch, Jewish Insider March 14, 2022) In the early 20th century, Jews in Yemen numbered over 50,000; today, there is one Jew left. There are reportedly a handful of “hidden Jews” in Yemen who have converted to Islam but secretly practice Judaism.

Yemenite Jews have a unique religious tradition that separates them from Ashkenazi, Sephardi, and other Jewish groups. The roots of the Jews in Yemen—Teiman in Hebrew— can be traced back to Biblical times. Yemen is mentioned in Jewish scriptures in various places. It is noted as the place of origin of Job’s friend Eliphaz. Additionally, the famed Queen of Sheba, discussed in the Book of Kings where she visits King Solomon, is said to have heard about King Solomon from Jews in Yemen, which was located near the kingdom of Sheba.

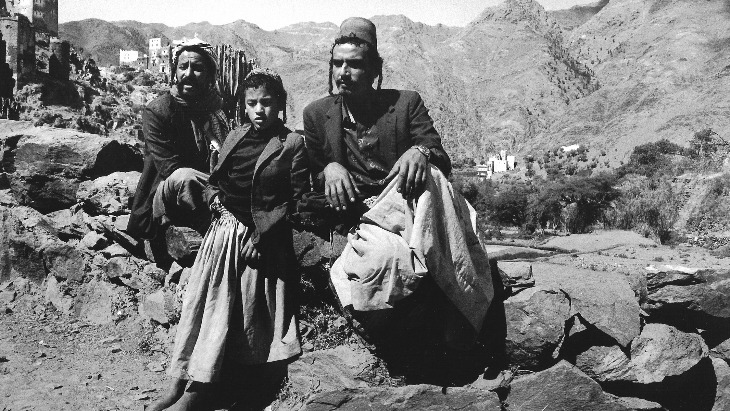

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1984, Photo: Myriam Tangi

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1984, Photo: Myriam Tangi

Although the province is not mentioned in the Mishna or the Talmud, there is an assumed reference in Josephus’s book, “The Jewish War.” Josephus states that he had informed “the remotest Arabians” regarding the destruction, and the assumption is that he is referring to the Jews of Yemen.

The immigration of the majority of Jews into Yemen appears to have taken place at the beginning of the 2nd century. In the ancient Jewish cemetery at Beth Shearim, there is an inscription in one of the rooms, describing those buried there as “people of Himyar” (the Yemenite Kingdom). The assumption is that their bodies were sent from Yemen for burial in Israel, not that they died while visiting Israel, just as many people today ask to be buried in the Land of Israel.

There are fascinating legends regarding how the Jewish community in Yemen was founded.

One local Yemenite Jewish tradition says that Jews came to the Arabian Peninsula at the time of King Solomon. Some say this was because King Solomon sent Jewish merchants to Yemen to prospect for gold and silver to use for the Temple in Jerusalem. Others say Jewish artisans were sent to the region when they were requested by the Queen of Sheba, during that same time period.

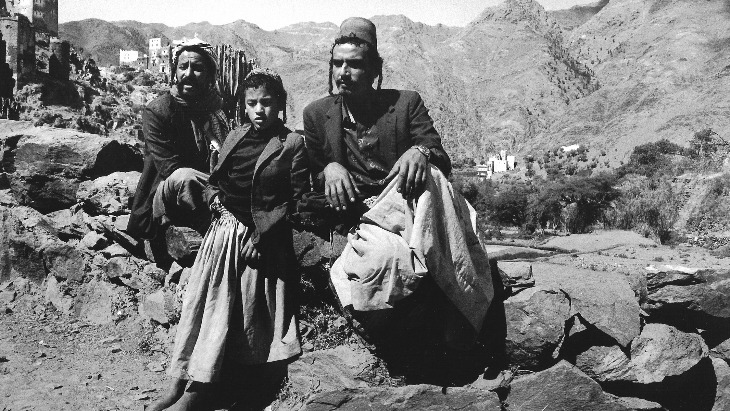

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1984, Photo: Myriam Tangi

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1984, Photo: Myriam Tangi

Another tradition, that of the Jews of Saana, states that their ancestors settled in Yemen 42 years before the destruction of the First Temple. It is also said that in the time of the prophet Jeremiah approximately 75,000 Jews, including Kohanim and Levites, traveled to Yemen.

The tradition of the Jews of Habban (southern Yemen) is that they are the descendants of the tribe of Judah that belonged to a brigade dispatched by Herod the Great to assist the Roman legions fighting in the region. The tradition is that they arrived in the area before the destruction of the Second Temple, and did not return to the Land of Israel.

Jews that lived in the Arabian Peninsula before the Roman period concentrated mainly in two areas – Yemen and Hejaz (today's Northwest Saudi Arabia).

There is a fascinating story regarding the King of Himyar and the Jews. Apparently, King Abu-Kariba Assad laid siege to Yathrib (modern-day Medina) to avenge the death of his son who had been killed by the inhabitants of the city. During the siege, the king became deathly ill and two medically knowledgeable Jews from Yathrib, Kaab, and Assad, entered the enemy camp and saved his life. After hearing the king, they pleaded with him to lift the siege and make peace with the city.

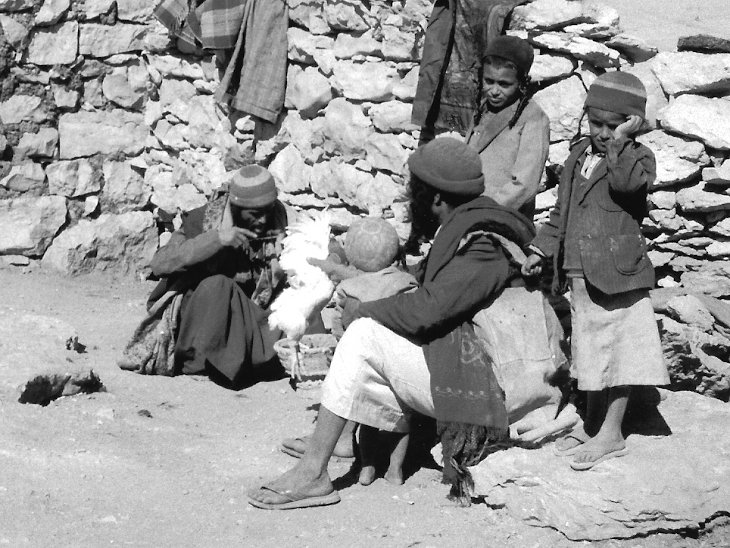

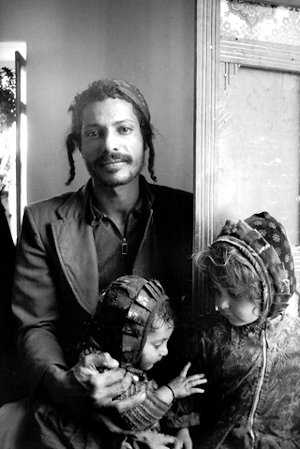

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1983. Photo: Myriam Tangi

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1983. Photo: Myriam Tangi

Not only did the king end the war, but he was also so impressed with the Jews that he embraced Judaism, along with his entire army. Upon his return home, he brought two Jews back with him to teach the populace and insisted that all his people convert to Judaism. The conversions, however, were not total, and there remained as many pagans as Jews in the land. There is also debate whether he converted out of genuine belief or out of political expedience. It is clear though that Judaism flourished in Himyar at this time, and many inscriptions with Jewish terms (“God of Israel”) are found dating to the 6th and 7th centuries.

The size of the Jewish population of Yemen for the first five centuries C.E. remained steady at about 3,000. The Jews were scattered throughout the country but carried on extensive commerce with other locations, and thus the Jews possessed many Jewish texts, and were knowledgeable of their heritage, although there were few scholars at that time.

In 628 CE, some of non-Jewish Yemenite leaders and tribes converted to Islam. Shortly afterward, Mohammed sent his cousin Ali to Sana'a to create a strong Islamic central authority in Yemen.

During this period of Muslim rule, the Jews were designated as Ahl al-Kitab, protected People of the Book. They were granted freedom of religion conditional on their paying Jizya, a poll tax. Active Muslim persecution of the Jews began in full force under the Shiite-Zaydi clan (the sect currently followed by the fanatical anti-Semitic Houthis in Yemen), when they seized power from the more tolerant Sunni Muslims early in the 10th century.

Under the Zaydi rule, which lasted nearly 1,000 years, Jews were treated as second-class citizens and were oppressed by the rulers and population. They were considered impure, and could not touch a Muslim’s food, had to walk on a Muslim’s left side, could not build houses higher than a Muslim's or ride a camel or horse, and when riding on a mule or a donkey, they had to sit sideways. Upon entering the Muslim quarter, a Jew had to take off his footgear and walk barefoot. If attacked with stones or fists by Islamic youth, a Jew was not allowed to defend himself.

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1983. Photo: Myriam Tangi

Al Ajar, Haïdan, 1983. Photo: Myriam Tangi

The Orphan’s Decree was a law that if a father died, his children were to be taken by the state and forcibly converted to Islam. Although this law was largely ignored during Ottoman rule, during the period of Imam Yahya (1918–1948) in 1922, the cruel law was enforced with strictness. Orphaned Jews were abducted from the community, and neither pleas nor bribes were accepted to release them. The community and relatives of the orphans searched for ways to save the children from this tragedy, and at times were able to prevent the forced conversion by marrying off the children quickly, as a married person was considered an adult and not able to be taken by the state. Sometimes the children were able to be moved to a large city and hidden with a Jewish family and other times they were taken out of the country.

In the late 12th Century, a false prophet arose in Yemen and proclaimed that Judaism and Islam were now one and the same. He used quotes from the Torah to prove his claim, and since the majority of the population was not that learned, he was very influential. The greatest Torah scholar of Yemen, Yaakov ben Natanel al-Fayyumi, wrote to the Rambam (Maimonides) in 1172 to ask for his response. The Rambam responded with the soon-to-be-famous Iggeret Teiman, Letter to Yemen, elaborating on the answer and clarifying the foundations of Jewish belief. This letter made such an impression on the Jews of Yemen that they included the name of Rambam in the Ḳaddish prayer, praying that he live a long life and his name be blessed.

Following his Letter to Yemen, the rabbis of Yemen would send letters to the Rambam, and he would teach through the letters he sent. He also sent them a copy of his Mishneh Torah the codified Jewish law, and this magnum opus was copied meticulously in Yemen. In the Geniza in Cairo, many letters from the 12th century and onward were found, demonstrating the close connection between the Cairo community and the rabbis in Yemen that began with the Rambam.

Despite their geographic isolation, the Yemenite Jews maintained contact with important Jewish centers, particularly with Egypt and Babylonia. Throughout their history, they had great scholars.

In the 14th century, Rabbi Nathanael ben Isaiah wrote an Arabic commentary on the Bible. In the second half of the 15th century, Rabbi Saadia ben David al-Adani was the author of a commentary on the Bible, and Rabbi Abraham ben Solomon wrote on the Prophets.

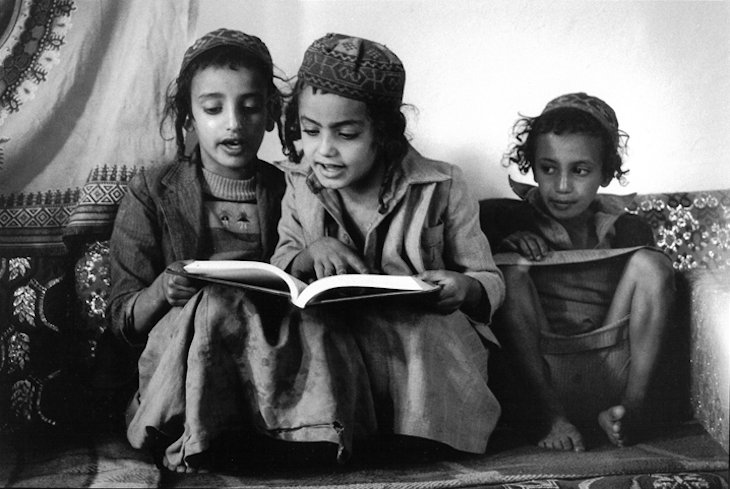

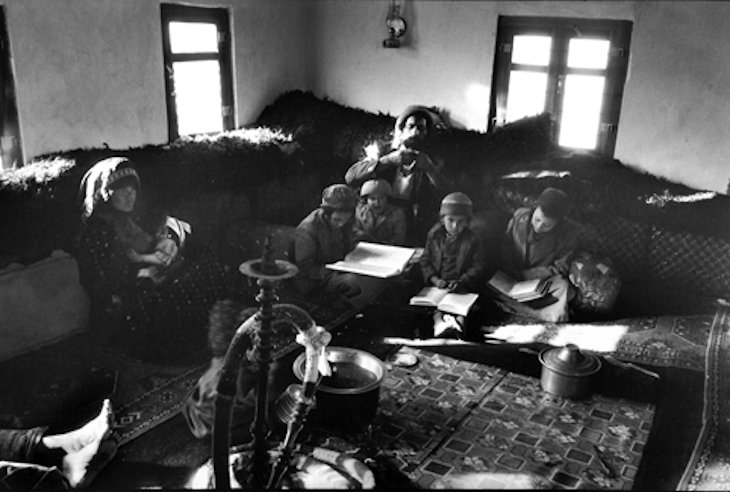

Study in the mufredj while the father is making tsitsit, Beit Sinan, Arhab, 1986. Photo: Myriam Tangi

Study in the mufredj while the father is making tsitsit, Beit Sinan, Arhab, 1986. Photo: Myriam Tangi

Rabbi Shlomo Adani (born 1567) was also a native of Yemen and is considered one of the greatest commentators on the Mishna. He was born in Sana'a, Yemen to Rabbi Yeshua Adani, a leading rabbi of the city. The family immigrated to the land of Israel in 1571, where he completed his book entitled Melechet Shlomo in 1624. His work is considered a classic and is partially printed in most of the editions of the Mishna with commentaries. There are also streets in Jerusalem, Beersheba, and other Israeli cities named after Rabbi Shlomo Adani.

Rabbi Shalom Sharabi, born in Yemen in 1720, is considered the father of all contemporary Sephardic kabbalists. After he was miraculously saved from a difficult situation, he fulfilled his vow to go to the Holy Land of Israel and to live in Jerusalem.

When travel became easier with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Jews began to emigrate from Yemen to then-Palestine. Many of the Jews that moved during this time, which was approximately 10 percent of the population, settled in Jerusalem, Jaffa, or in agricultural settlements.

In 1922, when the government of Yemen began to harshly enforce the Orphan's Decree, as discussed in this article, even more Jews sought to immigrate.

Following the partition vote of 1947 in which the UN voted to split then-Palestine and give a country to Jews, Arab Muslims in Yemen, assisted by the local police force, began rioting and murdering, killing 82 Jews in Aden and destroying hundreds of Jewish homes. This paralyzed the Jewish community financially and frightened the Jews regarding their future in Yemen.

This increasingly perilous situation led to the emigration of virtually the entire Yemenite Jewish community between June 1949 and September 1950 in Operation Magic Carpet. During this period, over 50,000 Jews emigrated to Israel.

A more minor, continuous migration was allowed to continue until 1962 when a civil war put an abrupt halt to any further Jewish exodus.

Today the overwhelming majority of the half a million Jews worldwide of Yemenite descent live in Israel. They are the legacy of 2,000 years of Yemenite Jewry.

With thanks to the photographer Myriam Tangi for granting permission to use her photos (www.myriamtangi.com). Click here to read her article about Yemenite Jews.

Learn more about the global Jewish population with our article: 'How many Jews are there in the world?'.

In March 2022 the United Nations reported there is just one Jew in Yemen (Levi Salem Marhabi who has been imprisoned for helping smuggle a Torah scroll out of Yemen