Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

11 min read

How was the Tanach compiled, who wrote it, what is its theological significance, and do archeological finds support its historical claims?

The Jewish Bible, called the Tanach (תנ׳ך)—a Hebrew acronym for its three main sections: Torah, Neviim (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings)—is the primary work of the Written Law. The English word, Bible, is derived from the Greek, ta biblia, or, “the books,” which, in reference to the Tanach, indicates that it is a compilation, in this case, of 24 different books.

The Torah, also known as the Five Books of Moses, makes up the first five books of Tanach. The Torah is the foundational text of Judaism, and describes the origins of the Jewish people; their covenant, as well as the nature of their relationship, with God; and provides the tools—called “commandments”—used to establish, as well as maintain, that relationship. The Torah has greater authority in Jewish law than the other books of Tanach, and the commandments and the basics of Jewish belief are derived from the Torah alone.

Neviim, or Prophets, contains eight books of prophecy, and is divided into two sections. The first section, known as the Early Prophets, chronicles the story of the Jewish people from the time they enter the land of Israel—following Moses’s death—through their conquest and settlement of biblical Israel; the establishment of a Jewish monarchy and the centrality of Jerusalem; the nation’s subsequent division, internal strife, and ultimate downfall culminating with the sack of Jerusalem and exile to Babylon.

The second section, known as the Later Prophets, is a collection of exhortatory writings imploring the Jewish people to follow the Torah’s laws, stay committed to their belief in God, and also promises a future Messianic era.

Ketuvim, or Writings, comprises 11 books, which include historical perspectives, moral and ethical instruction, allusions to a future redemption, and the emotional, inspirational poetry found in the book of Psalms.

The Tanach is a collection of prophetic, as well as divinely inspired, works. According to the Talmud,1 God dictated the Torah to Moses,2 whose credibility and authority as a prophet is derived from the national revelation of the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai (see more below); Joshua wrote his eponymous book, as well as the last eight verses in the Torah (explaining Moses’s death).

Samuel wrote the books of Judges, Ruth, and Samuel, although the sections after his death—the bulk of the book of Samuel—were written by the prophets Gad and Nathan.

David wrote the book of Psalms, and that includes both the Psalms he wrote himself, as well as those written by others.3

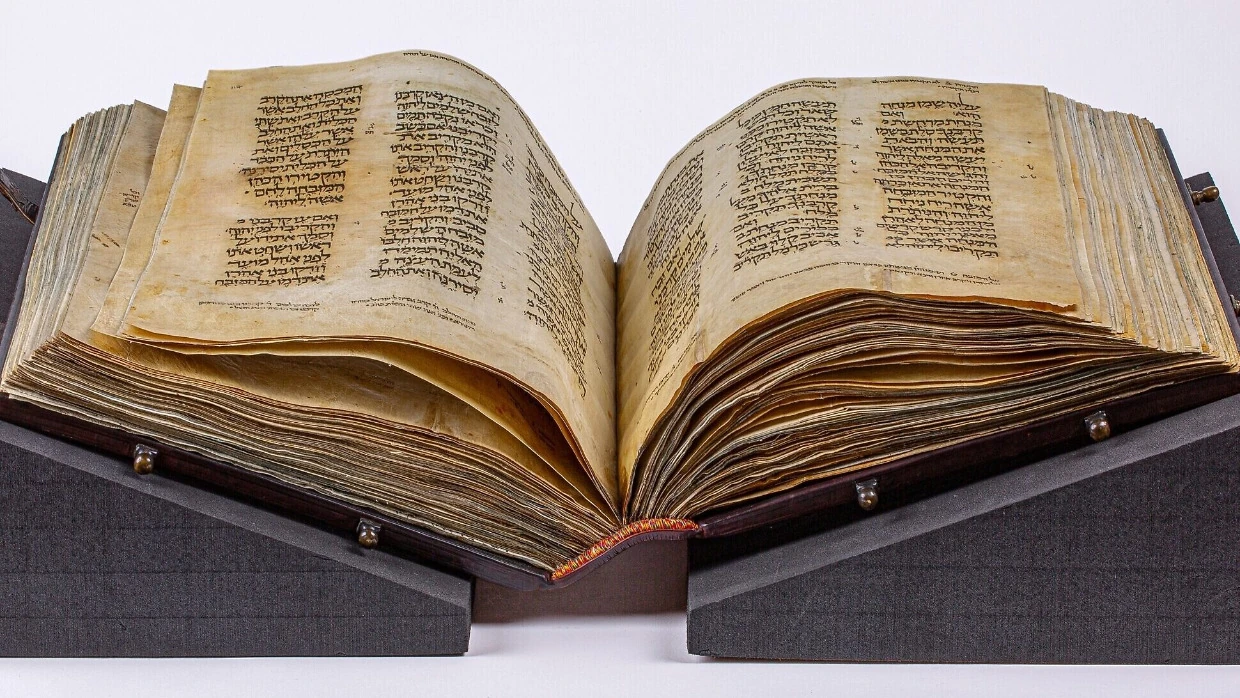

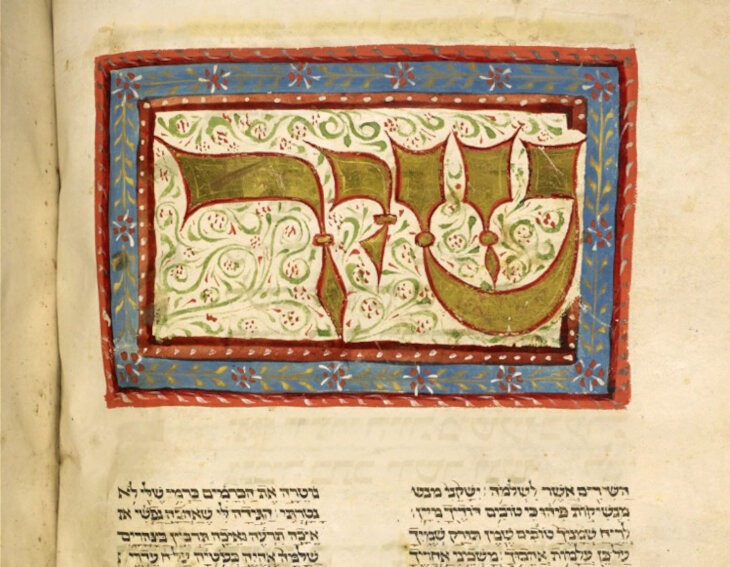

Ms. Parm. 1870 (Cod. De Rossi 510), the treasure of the Palatina Library in Parma, Italy.

Ms. Parm. 1870 (Cod. De Rossi 510), the treasure of the Palatina Library in Parma, Italy.

Jeremiah wrote his book, as well as the books of Kings and Lamentations.

The Talmud clarifies that Hezekiah and his colleagues compiled the book of Isaiah,4 as well as Proverbs, the Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes—which come from Solomon—based on Proverbs 25:1: “These are also the Proverbs of Solomon which the men of Hezekiah, king of Judah, transcribed.”5

The Great Assembly compiled the books of Ezekiel, the Twelve Minor Prophets, Daniel, and Esther; and Ezra wrote both the book of Ezra, as well as the genealogy in Chronicles up until his death, which was finished by Nehemiah.

Throughout the biblical period, the manuscripts that make up the Prophets and Writings—aside from the Torah, which the Jewish people had in its complete, final form from the time of Moses’s death in 1272 BCE—were compiled, edited, redacted, and finally canonized by the Great Assembly in the fourth century BCE.

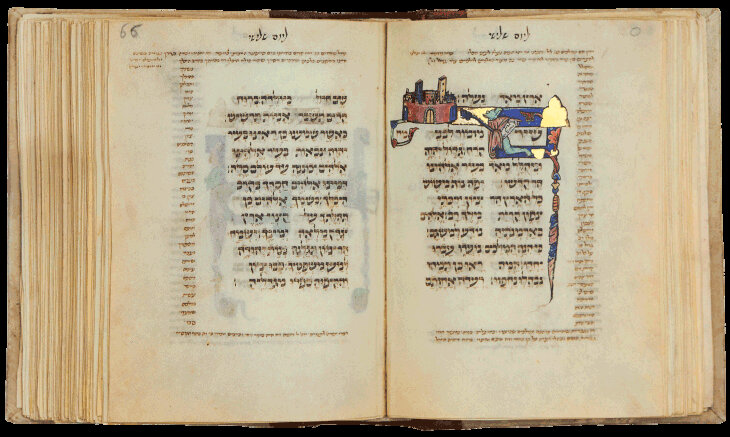

In the fourth century BCE, that era’s Jewish leaders—those returning to Israel from exile in what is today Iraq—expanded the Jewish high court, called the Sanhedrin, to 120 members. That governing body, known as the Great Assembly, did a number of things in order to standardize, as well as strengthen, Jewish practice and observance.

The Great Assembly composed the daily prayer service, along with other short prayers and supplications. They helped arrange the Oral Law into a more standardized system to preserve its integrity and accurate transmission. They enacted a number of laws and decrees. And they canonized the Tanach.

Canonizing the Tanach included focusing on basic philology: clarifying pronunciation, vowelization, and spelling for the different word forms and alternate readings; fixing the cantillation markings for how words are to be inflected and sung; and establishing the correct arrangement of verses, breaks, and chapter separations.

It also meant determining what texts would be included amongst Tanach’s 24 books. According to the Talmud,6 although the Great Assembly had thousands of recorded prophecies to choose from, “only prophecies considered necessary for later generations were [incorporated into the Tanach], the others, deemed unnecessary, were not.”

The Jewish Bible consists of 24 books, which are divided into three sections: Torah (the Five Books of Moses), Neviim (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings).

The Five Books of Moses are the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

The Prophets include the Early Prophets, which are the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings; as well as the Later Prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the 12 Minor Prophets (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zachariah, and Malachi). In most Bibles, the books of Samuel and Kings are divided into two books called Samuel I and Samuel II, and Kings I and King II. The compilers of the Septuagint, or Greek translation of the Bible, split the books into two, and that was incorporated into Christian Latin-language Bibles in the fourth century, and eventually Jewish Bibles in the 16th century.

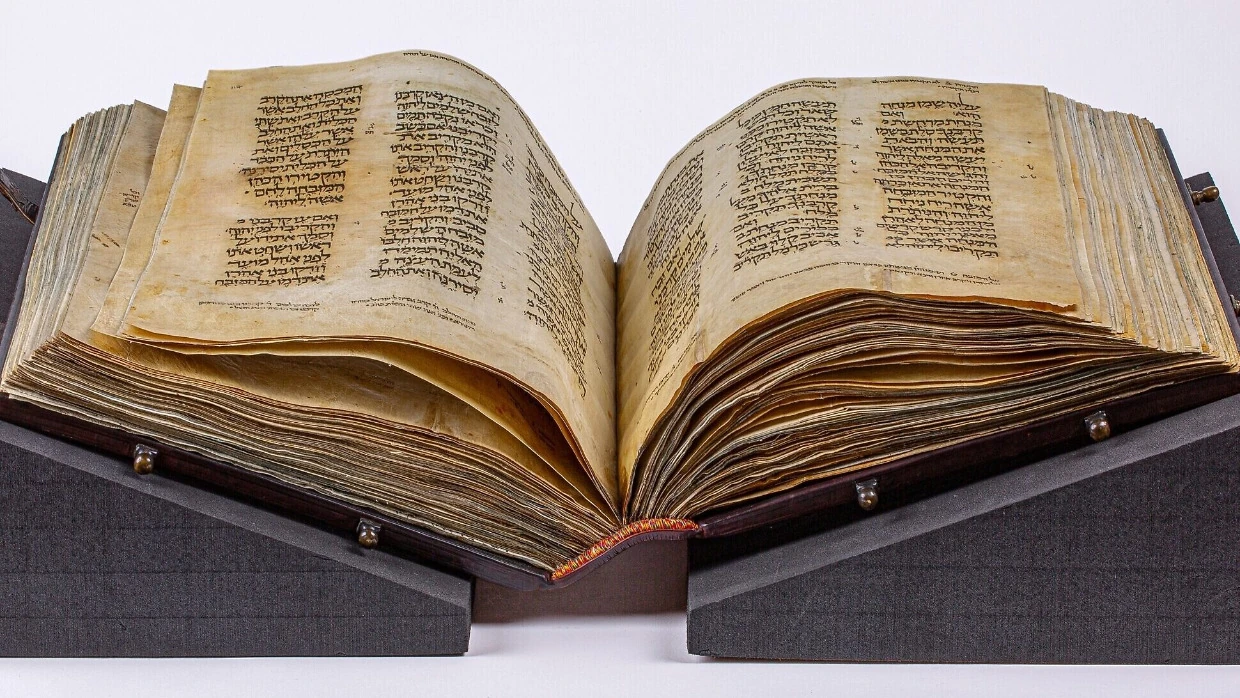

Song of Songs in a 14th c. manuscript of the Pentateuch and Five Scrolls, MS 19776, f.117v. British Library

Song of Songs in a 14th c. manuscript of the Pentateuch and Five Scrolls, MS 19776, f.117v. British Library

The Writings are the books of Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles. Similar to the books of Samuel and Kings, Chronicles was also divided into two books in the Septuagint, and eventually into Jewish Bibles as well.

The Torah’s authority derives from the Revelation at Mount Sinai (1312 BCE)—as chronicled in Exodus, chapters 19 and 20—when the entire Jewish nation, en masse, experienced a prophetic revelation of the Ten Commandments. That event obligated the Jewish people in Torah observance, and also distinguished the Torah—or, more specifically, Moses’s credibility as a prophet—from the other parts of Tanach, which don’t have the same force in Jewish practice and law. That authority is also recognized throughout the rest of Tanach, which makes numerous references to the “Torah of Moses”—as well as its language and content—and exhorts the Jewish people to adhere to its message and laws.

Contrary to the views of the minimalist school of archaeology, which claims that the “narratives of the Torah, along with the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and even the beginning of the book of Kings, have almost no historical basis,”7 the evidence seems to suggest otherwise.

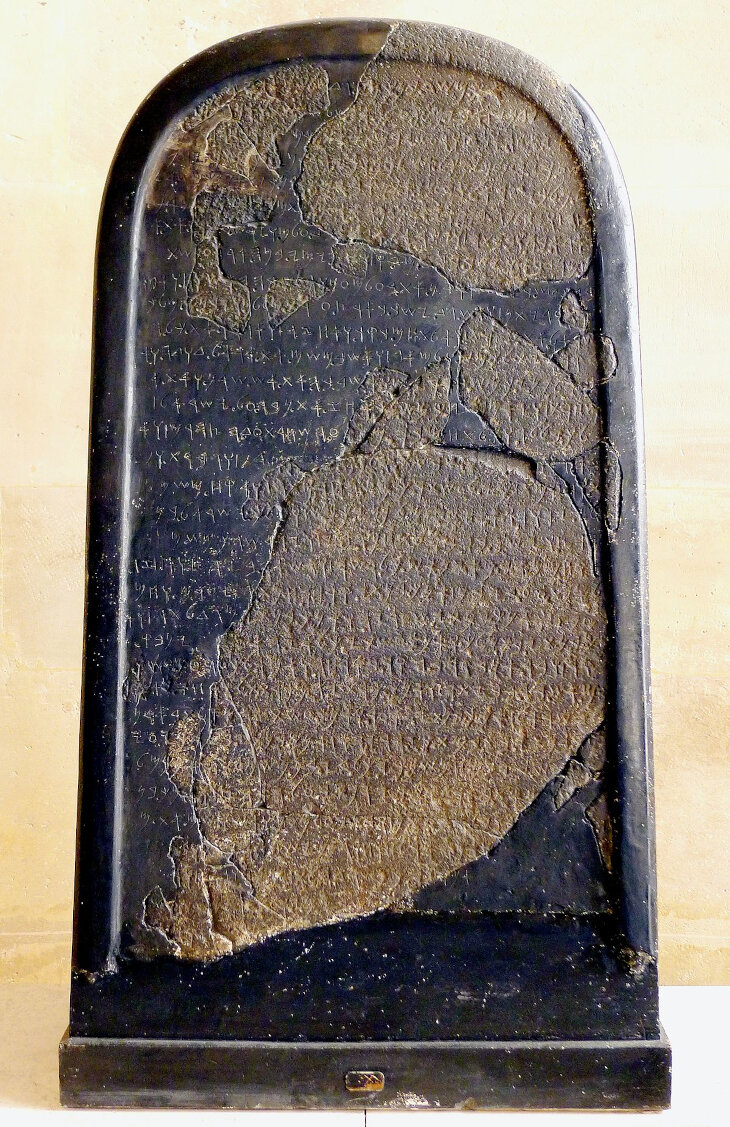

A number of examples, found in Israel and elsewhere, indicate that most of the book of Kings is well-documented. For example, the Israelite king, Ahab, is mentioned, by name, on the Mesha Stele—which is significant since the Moabite king, Mesha, is also mentioned in the book of Kings—as well as on the Kurkh Monolith found in Turkey. The Tel Dan stele, found in northern Israel, mentions his son, Jehoram, as well as the “House of David.” The earliest known reference to “Israel” is the Merneptah Stele, which dates to the 13th century BCE.

The Mesha Stele at the Louvre: The brown fragments are pieces of the original stele, whereas the smoother black material is Ganneau's reconstruction from the 1870s.

The Mesha Stele at the Louvre: The brown fragments are pieces of the original stele, whereas the smoother black material is Ganneau's reconstruction from the 1870s.

Other examples include the Ketef Hinnom scrolls, which have been dated to the seventh century BCE, and include the Priestly Blessing from Numbers 6:24-26. A number of names mentioned in the book of Genesis—including the Akkadians, Sumerians, and Elamites who lived along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the centuries before the Babylonians—were lost to history until libraries of cuneiform tablets were uncovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in what is today Iraq. Many other examples, including findings that seem to support events like the exodus from Egypt, the conquest of Joshua, and the reigns of David and Solomon exist as well.8

The Jewish Bible, called the Tanach (תנ׳ך), is comprised of three works: the Torah, Neviim (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). It is a collection of prophetic, as well as divinely inspired, works, and it was redacted and compiled into its current form by the Great Assembly in the fourth century BCE. It contains 24 books, although the most consequential sections—in terms of its authority as a legal work—is the Torah. Much archeological evidence has been discovered, both in Israel as well as around the ancient near east, that corroborates some of its narrative sections.

The term, “Old Testament,” is Christian in origin, and Jews do not use it. “Testament” is derived from the Latin word testari meaning “to be a witness.” Christians call the Hebrew Bible the Old Testament because they believe God canceled the covenant he made with the Jews, and made a new covenant, or a “New Testament,” with the followers of Jesus. Jews deny that claim—God doesn’t “change His mind”—and the Jewish people are His eternal people. For Jews, the term “Old Testament” is considered a pejorative.9

Apocryphal works are texts that were not included amongst the 24 books of the Jewish Bible. Many of these books were written during the Second Temple Period (from the third century BCE until the year 70 of the common era). Some are well-known, and mentioned in the Talmud, but for various reasons were not preserved by the Jewish people. Ironically, some of them were incorporated into the Christian Bible, which some Christian denominations accept, and the details of a few significant Jewish events—like parts of the Hanukkah story—are known primarily from Christian sources.

The Jewish, or Hebrew, Bible is called the Tanach (תנ׳ך)—also sometimes spelled, “Tanakh”—which is a Hebrew acronym of its three main sections: Torah (תורה), Neviim (נביאים), and Ketuvim (כתובים).

The Torah, also known as the Five Books of Moses, is the foundational text of Jewish law, practice, and belief.

Neviim, or Prophets, contains eight books of prophecy, and is divided into two sections: the Early and Later Prophets. The Early Prophets tells the story of the Jewish people from the time they enter the land of Israel until the Babylonian conquest and destruction of Jerusalem. The Later Prophets is a collection of exhortatory writings imploring the Jewish people to follow the Torah’s laws, and to be steadfast in their belief in God.

Ketuvim, or Writings, comprises 11 books, which include historical perspectives, moral and ethical instruction, allusions to a future redemption, and emotional, inspirational poetry and prayer.

Sehr gut erklärt

Toda raba

Excellent. I finally understand.