Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

The building of the Colosseum was made possible by Rome’s destruction of Jerusalem 2,000 years ago.

Visitors to the ancient Colosseum in Rome are awed by its sheer size. Measuring 620 by 512 feet, it’s a massive structure; six and a half football fields could fit inside its space, with room to spare. Rising four stories into the sky, the Colosseum has 80 entrances and used to hold more than 50,000 spectators who flocked to this landmark to watch games during the height of the Roman Empire.

But few guidebooks mention why the Colosseum was built or how its sponsors could afford to build what was the largest amphitheater in the ancient world. The Colosseum was built to commemorate the sacking and destruction of Jerusalem, and was funded by loot stolen from the ancient Jewish Temple in Jerusalem.

A Jewish Temple stood in Jerusalem – barring a 73-year interruption – for nearly a millennium. King Solomon erected the First Temple in 827 BCE. It was a magnificently beautiful building, filled with gold and silver ornaments, including the Ark of the Covenant and the Menorah, a seven-branched candelabra formed out of one piece of solid gold. The First Temple stood for 404 years, forming the center of Jewish identity and worship.

Babylonia’s fearsome King Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple in 423 BCE. A generation later, in 350 BCE, the Second Temple was dedicated, nearly as beautiful as the First Temple. The Ark of the Covenant had been lost, looted by the Nebuchadnezzar’s troops, but many of the gold and silver vessels, as well as the golden Menorah, were restored. The Temple was enhanced further in 19 BCE, when the Roman-appointed, non-Jewish King Herod, seeking to shore up his popularity, rebuilt the Temple, enlarging it significantly and increasing its grandeur and beauty.

In the year 63 BCE, the expanding Roman empire captured Jerusalem. Hopelessly riven by internal divisions, Judea (the ancient Jewish homeland in present-day Israel) fell under an often brutal Roman occupation. For the next 113 years, the Jews were oppressed and harassed. Rather than coming together to fight their Roman overlords, Jews formed endless factions, each advocating a different course of action. Finally, in the year 66 CE, matters came to a head.

Rome’s Emperor Nero is remembered in popular imagination as “fiddling while Rome burned” during a massive conflagration that destroyed much of the city in the year 64. Two years later, he appointed a violent sadist, Gessius Florus, as procurator over Judah. Florus publicly humiliated the Jewish population. When Jewish children heckled him during a public appearance in Jerusalem, Florus ordered his troops to kill local Jews, slaughtering over 3,600 in one day. He then ordered the Jewish community leaders of the city to be publicly whipped and then crucified. That sparked a popular uprising that lasted for four years and is known as Rome’s “Jewish War.” For four long years, Jewish forces battled Roman troops, and were slowly crushed, first in the country’s north, then in other major population centers, and finally, in the year 70 CE, in Jerusalem.

For much of the Jewish Wars, the general in charge of regaining control of Judea was a man from relatively humble beginnings named Vespasian. After re-conquering most of Judea for Rome, he led four divisions of Rome’s fearsome army against Jerusalem, laying siege to the city and blocking the city’s thousands of Jewish residents from escaping.

Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by Francesco Hayez. Oil on canvas, 1867.

Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by Francesco Hayez. Oil on canvas, 1867.

The Talmud documents some of Vespasian’s deeds and interactions with the beleaguered Jews. One day, the great Jewish sage Rabbi Yochanan had himself smuggled out of Jerusalem in a coffin, ostensibly to be buried outside the city walls. Rabbi Yochanan was discovered, and brought to Vespasian for questioning. When Rabbi Yochanan saw the fearsome general Vespasian, he greeted him as king. Vespasian protested that he was not king; Rabbi Yochanan replied, “In truth, you are a king; if not now, then in the future” (Gittin 56b). While Vespasian and Rabbi Yochanan conversed, a messenger arrived, informing Vespasian that the emperor had died and he was to be Rome’s next supreme leader.

Vespasian explained to Rabbi Yochanan that he would send another general to take over the siege of Jerusalem, but asked if there was anything he could do for this great Jewish sage who had predicted his political rise. Rabbi Yochanan asked that one city in Judea, Yavneh, be spared total destruction, and that Vespasian spare the lives of some of the Jewish sages. Vespasian agreed.

The general Vespasian sent to take over besieging Jerusalem was Titus. Titus tried attacking the defensive walls surrounding Jerusalem, and eventually concluded that his easiest route to victory was to starve out the Jews barricaded inside. Jews who tried to escape the starving city were tortured; the Jewish historian Josephus describes Roman troops disemboweling Jews who tried to leave.

Emperor Titus

Emperor Titus

Just after Passover in the year 70 CE, Titus gave the order to attack Jerusalem’s city walls. Troops catapulted boulders into the city and attacked the walls with battering rams. Titus offered prizes to the first soldiers who could battle their way into the center of the city and scale the walls of the Jewish Temple within. After months of hand to hand combat, in high summer, Titus prevailed. His troops set fire to the Temple and Titus ordered the wholesale destruction of the entire city of Jerusalem. Nothing was to remain. Titus’ troops plundered the many priceless gold and silver vessels and decorations of the Temple, taking them as spoils of war.

To celebrate his victory, Titus distributed spoils to his soldiers and ordered a three-day party for his troops. He forced many of the captured Jews to fight wild animals in gruesome gladiatorial battles to entertain his troops. Afterwards, Titus returned home to Rome with about 50,000 Jewish captives as slaves. Among them were two Jewish military leaders, Yochanan ben Levi (also known as John of Giscala) and Simeon ben Giora, who’d fought valiantly, and whose capture was a particular feather in Titus’ cap.

The highlight of every Roman military victory was the vast triumphal procession back home in Rome afterwards. Cambridge University classics professor Dr. Mary Beard explains that successful generals led triumphal processions in the heart of Rome, in which they displayed the many slaves, prisoners of war, and booty they’d looted in foreign conflicts. These parades were a centerpiece of Roman imperial identity.

“The triumphal processions of victorious generals offered one of the most impressive windows onto the outside (world). When the Roman crowds lined the streets to welcome home their conquering armies, which paraded through the city with their profits and plunder on display, it was not only the astounding wealth that impressed them…it was also the dazzling display of foreign lands and customs that captured the popular imagination” (quoted in SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard: 2015).

Titus’ triumphal procession was an especially awe-inspiring event. Some processes took several days to display all the looted materials, wealth, and slaves taken from far-away lands. It seems that Titus’ procession celebrating his victory over Jerusalem was one of the more dazzling spectacles the city had ever seen. It was so memorable that Titus commissioned a massive triumphal arch erected in the Forum, the heart of ancient Rome, decorated with friezes (carvings) illustrating his victory parade, complete with Jewish slaves, captives, and looted goods including the Temple’s golden Menorah. The arch reminded Romans of their empire’s triumph in the Jewish War, and has stood for nearly 2,000 years, dazzling visitors to this day.

A relief in The Arch of Titus depicting the exile of the Jews

A relief in The Arch of Titus depicting the exile of the Jews

Building the Colosseum

Titus became emperor nine years later, in 79 CE, and launched a vast building project to transform Rome. The centerpiece of his program was building a huge arena near the Forum which could seat 50,000 viewers and host the most lavish games that Rome had ever seen. (It was named the Colosseum after a nearby massive statue of the emperor Nero, called the Colossus.) The Colosseum was funded by booty from the Jewish War, and likely was built at least in large part by Titus’ 50,000 Jewish slaves.

Construction took ten years. It was grueling, backbreaking work, under the scorching sun of burning Roman summers. It’s unknown how many slaves died during its construction; their deaths, like their names and their lives, are lost to history.

Funded by the booty of Judea, including the precious golden and silver vessels and decorations from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, the Colosseum could not have been more different from the source of wealth which enabled its construction. Where the Jewish Temple has been a vehicle for holiness, the Colosseum housed an orgy of death.

When the Colosseum first opened to the public, Titus celebrated its inauguration with 100 days of games. These were fierce fights between gladiators, nearly always slaves, who were forced to fight, often to the death. Spectators also watched fierce animals fight each other; it is said that over 9,000 animals died during the Colosseum’s opening months. Gladiators often began their fights by saluting the emperor, saying “We, who are about to die, salute you.” Bloodstains remain on the floors of the Colosseum’s holding cells today.

The Colosseum soon adopted a pattern. It was open most days, and featured three different kinds of spectacles. In the morning, wild animals were released into the arena to fight one another. Afterwards, around lunch time, prisoners were publicly executed. In the afternoons came the most popular games: violent fights between gladiators. Gladiators were forced to give the jeering crowd a show, trying their hardest to wound and kill their fellow slave opponents. In order to prevent gladiators from feigning death in order to escape from a fight, collapsed gladiators were stabbed with a red-hot spear in front of the cheering crowd.

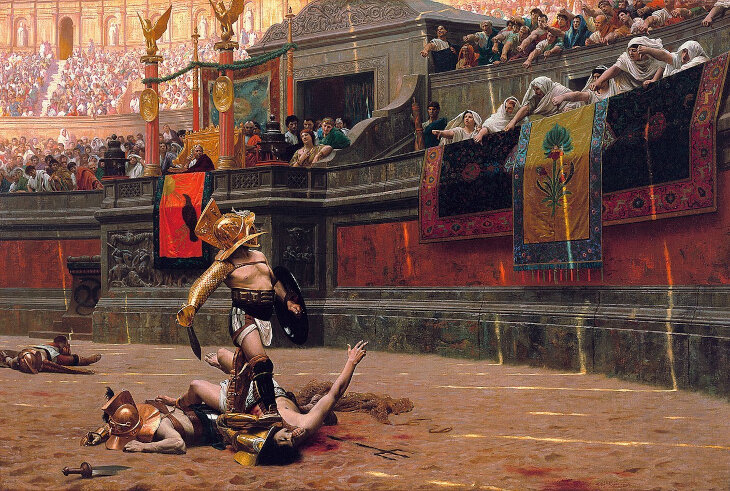

Jean-Léon Gérôme's Pollice Verso, the name Latin for "with a turned thumb."

Jean-Léon Gérôme's Pollice Verso, the name Latin for "with a turned thumb."

When a gladiator was wounded, the sponsor of that day’s games – the emperor or another prominent Roman citizen – would get to decide whether the wounded gladiator lived or died. The sponsor would listen to the crowd’s screams. If they were yelling to spare his life, the sponsor would often take their cue and give a thumbs-up sign, indicating that the gladiator could live and fight another day. The crowd often brayed for the gladiator’s death. If he chose to listen to the crowd, the sponsor would give a thumbs-down sign: then the gladiator was gruesomely murdered before the jeering audience.

The Colosseum’s horrific violence lasted for nearly 400 years; the last gladiatorial combat there took place in 438 CE. The stones of the Colosseum are soaked – literally and metaphorically – with the blood of countless numbers of people who met their deaths in terrible ways there.

Tourists who explore its seating areas and the vast underground complex where slaves and animals were kept are walking in one of the most grisly sites on earth. The fact that it was built and paid for with Jewish suffering only adds to its horror.

View this post on Instagram

According to a reconstructed inscription found on the site, "the emperor Vespasian ordered this new amphitheatre to be erected from his general's share of the booty." I would not be suprized if this included the gold reigious objects from the destroyed 2d Temple in Jerusalem