Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

10 min read

I wonder which version of my father I miss more. The authentic version, homeless and free, or the version I created, safe and caged.

In February of 2017 at LaGuardia Airport, some tired travelers collecting their luggage from Terminal B will have to step over a man lying on the floor in a green sleeping bag.

Those who pause to inspect him more closely will notice that he’s bald and doesn’t have many teeth, that he’s older, perhaps in his 70s. Those who lean in closer may recoil at a pungent whiff of his sweetly sickening body odor.

If any traveler were to rouse him and try to engage him, and most certainly none did, they might learn that he is a retired doctor, that he had sailed the Atlantic a few years before – twice and alone. Or that he has four children and eight grandchildren, and no history of substance abuse.

I know the life story of that man in the sleeping bag because he was my father. And I know what happened that February night because two police officers did rouse him.

“Hello, this is Sergeant Rossi. Susan Greene? Is your father John?”

I said he was.

“We can have him home to you within about an hour.”

I groaned. “This isn’t his home. He’s homeless. Please, I have young kids here. Can’t you take him to a hospital?”

“Sorry ma’am. He’s not physically distressed, doesn’t appear to pose a risk to himself or others. We can’t bring him unless he consents.” He paused. “How ‘bout this. My partner’ll try talking to him calmly, maybe we can convince him to go voluntarily.”

A moment later, I heard a quiet voice in the background, stripped of the obstinance to which I had grown accustomed through the years. I barely recognized the mumble as my father’s.

“I’ll go,” he said.

Within six hours, my homeless, itinerant, recalcitrant father was institutionalized, first in an emergency room and then in a psychiatric hospital. Then, while I seized power over him as his legal guardian, in a nursing home overlooking the ocean. Thus began the next phase of this relationship that ended with his death, five years later. Throughout the course of our relationship, power ebbed and flowed between us like an ocean tide, until finally, I thrust upon him this “normalcy” I had always wished for him.

But “normalcy” meant taking away his freedom. And now that he is gone, I wonder which version of my father I miss more. The authentic version, homeless and free, or the version I created, safe and caged.

Up until the nursing home, my father lived a big and confusing and contradictory life. I struggled to relate to him. I will say, generously, that he was like an onion. Lots of layers. That and he made me cry a lot. But he also added spice. He pushed me to think and act beyond conventional expectations. Dad was born to wealthy parents. He lived for years in a Gatsby-esque home on the North Shore of Long Island and, after that, in a gated home in Bermuda. He attended boarding school in Switzerland, and, ultimately, became a doctor.

Throughout, he was miserable. It may have been the combination of a volatile father, a withdrawn wisp of a mother, or the fact that spending more and more money seemed to be the salve for which that family always reached. And so, my own father hated conspicuous consumption in that kind of way that only the rich can afford.

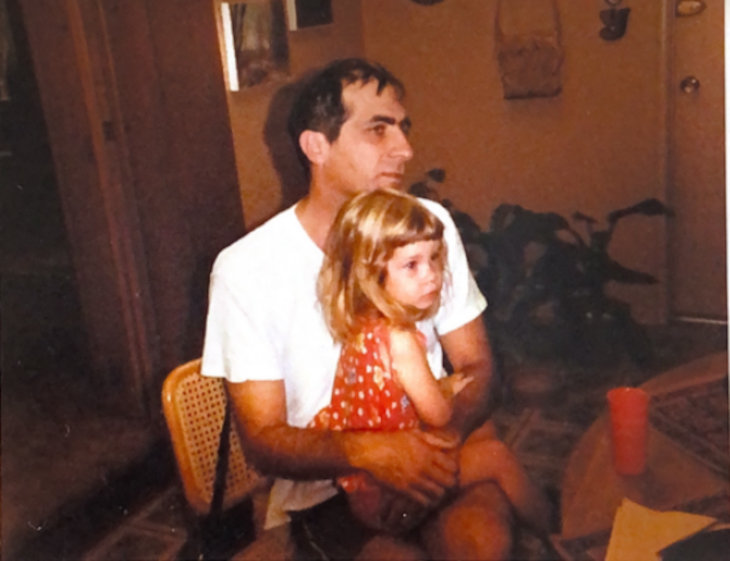

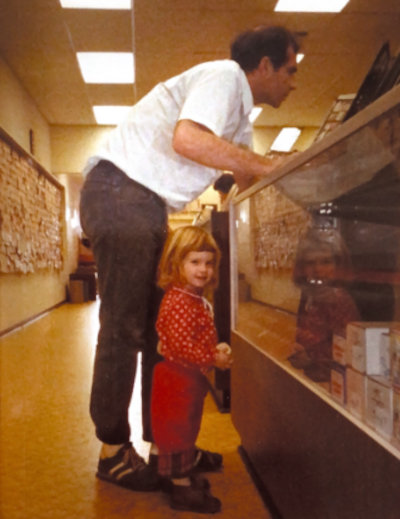

Once he was in control of his own money, he locked it away and decided that he would parent differently. And differently, he did. Deprivation replaced opulence. For the first several years of my life, we did not have a permanent home. We shuttled between inexpensive rentals and the homes of family members who would indulge a miserly, wealthy man. My mother, the only kind of calming and loving parental presence who could reasonably counterbalance my father, toiled away to come as close as possible to making impossibly far ends meet. Dad’s medical career was intermittent.

Eventually, even my preternaturally accepting mother had enough and left my father, moving us to a tiny apartment about an hour away. This would have been a good time for my mother to divorce my father and force open his coffers. But she didn’t.

“If you divorce me, if you take me to court, I will commit suicide,” explained my father. And my mother, God bless her, believed him.

We lived on her meager wage as a per diem nurse working the night shift. She slept on the couch of our upstate New York apartment, filled the refrigerator with what she could afford, and cut her blood pressure medication in half to make it last twice as long.

Dad didn’t disappear, though. Far from it. Misguided or not, he had a firm plan for my upbringing and it involved showing me that money, and society’s expectations of how to use it, was not the key to a meaningful life. He wanted to prove his parents wrong.

After my mother left, my father moved into an unwinterized, plywood shack at the far corner of his older brother’s Long Island estate. This setup worked for a time, particularly because Dad could live there for free. He set up space heaters, bought a mini fridge and a toaster oven, purchased second-hand mattresses, and picked me up for weekend visits. He would prepare meals for us. A favorite was spaghetti cooked by leaving it to sit in a pot of water for several hours. This would soften it just enough to approximate “al dente.” Dad did not know what “al dente” was. He just didn’t have gas to boil the water. Then he would place two generically branded soy burgers in the toaster oven and jump up when the oven dinged. He’d pick them up with the tips of his fingers and squeal as he quickly volleyed the burning hot patties between his fingers – the shack did not have oven mitts – and then crumble the patties over the spaghetti. He finished the plates with a generous sprinkling of soy sauce.

Over dinner, we would discuss Don Quixote, climate change, various careers I might consider (“Never, Susan, never for the money. Never pick a job for the money,” was his religious admonishment.). Of course, the more you deprive a child of something, the more she wants it. And I really wanted enough money to afford a stove upon which to cook spaghetti and a health plan to cover blood pressure medication. That may be why I became a lawyer.

But I won’t say that Dad’s unusual positions did not have at least some of their desired effect. I have a broad view of the world and a clear understanding of what I do and don’t want from it. I think I can thank my father for that but give me a few more years and a few more thousand dollars of therapy before I can reach a firm conclusion.

Dad’s shack time was, however, relatively brief. Eventually, an argument with his brother relating to the proper division of a $50 cable bill extinguished the possibility of rent-free living there. That and some further displeasure about Dad’s personal hygiene. This eviction was a problem, because rent-free living was the only kind of living my father was willing to do.

From there, Dad lived in various other “rent-free” spaces. His Toyota Corolla and a number of highway rest areas (Sloatsburg, New York being his favorite), my mother’s couch, a reclining chair in my college dorm’s common room (that only lasted about a night), a tiny, 23-foot sailboat that he miraculously sailed from New York to Bermuda and back and then from Florida to the Canary Islands and back when he was in his 60s, and then, finally, a sleeping bag in LaGuardia Airport where those two kind police officers convinced him to go to an emergency room.

“Alzheimer’s Disease,” concluded the doctor in a phone call to me the next day, finally naming the nameless eccentricities that had plagued his life and mine. “He’ll need round-the-clock care; I suggest a nursing home equipped with a dementia unit.”

Thus, the inevitable choice: nursing home or ice floe. And I don’t suggest ice floe lightly – that directive came straight from a lucid version of my father.

Of my fear that he would die on one of his oceanic voyages, he opined that “Ending up at the bottom of the Atlantic is a hell of a lot better than in some nursing home.” It wasn’t the first time Dad had said such things. We once drove by a nursing home aptly named, “Trail’s End.” Dad laughed and laughed, then turned to me, all trace of humor evaporated, “Never, Susan, never put me in a nursing home. If I can’t kill myself first, say goodbye and then send me out into the Atlantic on one of those ice floes. Or a little dinghy. Whatever you can get ahold of.”

I’m still not sure which was the right choice, but the nursing home seemed the path of least resistance. So, I took it. And what choice did I have. Had I followed my father’s wishes, I imagine I’d be writing this from jail. That would have been hard on my kids.

The last five years of my father’s life were his worst nightmare. My impossible father, who maddened me, worried me, and pushed me to strive to excel and to question what was generally accepted as a proper path, was reduced to a desiccated shell of a human being, with a slackened face and a vacant stare. At times, I would look murderously at the pillow propped at the top of his bed. Sometimes, I wondered if there were security cameras in the room.

When he eventually died last year, I felt relieved. But I remain haunted by the choice I made to send him to his death in a gray institution overlooking the water. And not, as he wished, sending him to his death in a little raft on those same waters for one last adventure.

For Father’s Day this year, my family and I will honor my dad by fulfilling the mitzvah of feeding the hungry by providing meals to homeless shelters. And I will remind my daughters that each of us on this earth was made in God’s image. Even the people in sleeping bags whom we might trip over as we rush through our busy lives.

I will encourage my daughters to stop and pay attention to people. I will remind them that sometimes the most interesting people are the people who don’t look like everybody else or act like everybody else. Despite the enormous difficulties I had in my relationship with my father, I loved him very much. And I miss him.