Free Will, God, and the Logic of Choice

Free Will, God, and the Logic of Choice

16 min read

Though Lawrence was unquestionably dedicated to the Arab cause, historians have shown that his views on the Middle East were far more complex than previously assumed.

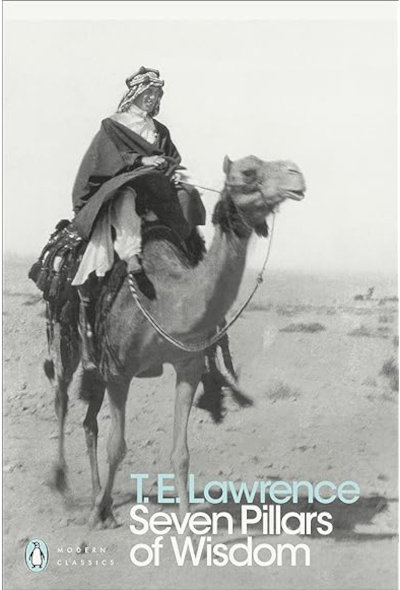

Was he the champion of Arab nationalism - or a secret Zionist? T.E. Lawrence, better known as "Lawrence of Arabia," remains one of the most enigmatic figures of the early 20th century. His exploits during World War I as a liaison officer with Arab rebel forces fighting against the Ottoman Turks have been immortalized in print, stage and film. Lawrence's 1922 memoir "Seven Pillars of Wisdom" is considered a literary classic, while David Lean's 1962 epic "Lawrence of Arabia" won seven Academy Awards and is frequently cited as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made.

For decades after his untimely death in 1935, Lawrence was viewed as a heroic champion of Arab independence and nationalism. He developed close friendships with Arab leaders like Emir Faisal and was frequently seen in public wearing an Arabian robe and headdress. His impassioned advocacy for Arab self-determination following World War I cemented his legacy as a dedicated Arabist. Lawrence's identification with the Arab cause appeared so complete that he refused to accept the award of Commander of the Bath from King George V, explaining that he could not possibly accept any honor while Britain was "about to dishonor the pledges which he had made in her name to the Arabs who had fought so bravely."

Given his identification with the Arab cause, few would have listed him among the friends of the Jewish people or the Zionist project. Yet in recent years, historians have begun to uncover a more complex picture of Lawrence's views on the Middle East - one that reveals him to have been a committed supporter of Zionism and Jewish settlement in Palestine.

Thomas Edward Lawrence, born in 1888 in Wales, showed an early passion for history and archaeology. He studied at Oxford, where he combined academic studies with adventurous travels, including a solo 1,000-mile trek through Ottoman Syria in 1909. His archaeological work in the Middle East proved invaluable when he enlisted in the British Army at the outbreak of World War I.

In 1916, Lawrence was assigned to Hejaz to work with Arab forces against the Ottoman Turks, a role that would define his legacy. As a liaison between British and Arab leaders, he developed a close friendship with Emir Feisal, who would later be crowned King of Iraq. But Lawrence was also an innovative military strategist. He orchestrated sudden strikes and sabotage operations that inflicted significant damage on Turkish forces while minimizing Arab casualties. His crowning achievement came in 1917, with the capture of Aqaba, a strategic port city only a few miles from modern day Eilat.

In contrast to his military successes, Lawrence's post-war efforts to secure Arab independence were thwarted by the secret Anglo-French Sykes-Picot agreement, in which the great powers agreed to divide up the Middle East amongst themselves. Disillusioned, he briefly advised Winston Churchill before withdrawing from public life, joining the Royal Air Force under an assumed name. In 1926, Lawrence published "Seven Pillars of Wisdom," his memoir of the Arab Revolt, which cemented his fame as "Lawrence of Arabia" and inspired numerous books and films about his exploits.

Though Lawrence was unquestionably dedicated to the Arab cause, historians have shown that his views on the Middle East were far more complex than previously assumed. It turns out that the Arabist was also a philo-semite who deeply appreciated the uniqueness of the Jewish people. In his writings, he refers to the “the everlasting miracle of Jewry,”1 acknowledging the millennia-long relationship between the people and land of Israel. “The Jewish experiment is a conscious effort, on the part of the least European people in Europe, to make head against the drift of the ages, and return once more to the Orient from which they came.”2

The Arabist was also a philo-semite who deeply appreciated the uniqueness of the Jewish people, referring to the “the everlasting miracle of Jewry.”

Lawrence's Zionist sympathies were not widely known, but some of his antisemitic British contemporaries had their suspicions. As Lawrence was preparing to publish his memoir, he reached out to Rudyard Kipling for feedback on the manuscript. Kipling's response was revealing: he agreed to review the proofs, but if the text showed Lawrence to be "pro-Yid," he would return the manuscript untouched.3

The great adventurer’s “pro-Yid” orientation shaped his vision for the future of the Middle East. Despite his deep engagement with Arab culture and his role in the Arab Revolt, Lawrence was well aware of the flaws and failures of Arab society. He believed the Arab world had fallen into a state of decline and was ill-equipped to modernize on its own. He often drew stark contrasts between the intellectual and artistic achievements of the medieval Arab world and the cultural stagnation of modern Arabs. "They are a limited narrow-minded people whose inert intellects lie incuriously fallow. Their imaginations are keen but not creative. There is so little Arab art today in Asia that they can nearly be said to have no art… They show no longing for great industry, no organizations of mind or body anywhere. They invent no systems of philosophy or mythologies."4

Historian Martin Gilbert suggests that despite his reputation, Lawrence "had a sort of contempt for the Arabs," and believed that "only with a Jewish presence and state would the Arabs ever make anything of themselves and move into the 20th century."5 A people known for their hard word work and ingenuity, an influx of Jews could revitalize the holy land and ultimately the entire Middle East.

Already as a 21-year-old, while traveling through the Galilee in 1909, he reflected on the holy land’s past and the Zionist settlers arriving to farm the land. “Palestine was a decent country then, and could so easily be made so again. The sooner the Jews farm it all the better: Their colonies are bright spots in a desert.”6 As Jewish pioneers overcame malaria and hostile neighbors while working night and day to bring the devastated soil of the holy land back to life, Lawrence “looked on with amazement and admiration… During his visits to Palestine he had an opportunity of watching Jewish efforts and observing their rapid achievements. This release of Jewish zeal and energy appealed to his dramatic instincts, and, with his keen perception, he discerned the possibilities of this historic enterprise… His faith in the Jewish National Home grew correspondingly with the growth and development of Palestine as a result of Jewish efforts.”7

In 1918, on the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, he told a Jewish newspaper: “Speaking entirely as a non-Jew, I am decidedly in favor of Zionism; indeed I look on the Jew as the natural importers of western leaven so necessary for countries of the Near East.”8

Lawrence expanded on this view in a 1920 article for The Round Table, where he argued that Jewish settlers would bring "samples of all the knowledge and technique of Europe" to Palestine. He predicted that their success would ultimately raise the living standards of the Arab population as well: "The success of their scheme will involve inevitably the raising of the present Arab population to their own material level, only a little after themselves in point of time, and the consequences might be of the highest importance for the future of the Arab world. It might well prove a source of technical supply rendering them independent of industrial Europe, and in that case the new confederation might become a formidable element of world power."

Unlike the Arabs themselves who viewed Jewish immigration as a threat, Lawrence saw Zionism as a potential catalyst for regional modernization and development rather than a danger to Arab interests. His support for Jewish settlement was rooted in a belief that it would ultimately benefit both Jews and Arabs, bringing much-needed skills, capital, and innovation to a region desperately in need of revitalization.

Lawrence's support for Zionism was significantly influenced by his close friendship with Chaim Weizmann, Britain’s leading Zionist who would later become the first President of Israel. The two men first met in Aqaba shortly after the British government issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, and their conversation immediately turned to Zionism. Lawrence explained that he believed Zionism to be “morally justified” and that he was personally moved by the historic significance of the “messianic trumpet-call.” However, he voiced skepticism about whether Jews would respond, asking Weizmann, “Would not this trumpet-call fall on deaf ears?”

Weizmann expressed his faith in the Jewish people, describing their wild joy in response to the Balfour declaration. Reflecting on Weizmann’s words, Lawrence said that he would “wait and watch with the deepest interest the development of the Jewish National Home. If Jews succeeded in translating the policy embodied in the Balfour Declaration [to action by establishing a state], it would certainly be a performance unique in the history of mankind.”9

Weizmann made a powerful impression on Lawrence. Later, in an unsent draft letter to the Anglican Bishop of Jerusalem, he referred to Weizmann as "a great man whose boots neither you nor I, my dear Bishop, are fit to black."10 For his part, Weizmann was initially apprehensive about Lawrence's stance on Zionism but was relieved to find him "not only friendly to the ideals embodied in Zionism but fully conversant on the subject."11 Weizmann emphasized that contrary to some persisting misconceptions, Lawrence never saw Zionism as incompatible with Arab interests or with British assurances to the Arabs.

Lawrence's commitment to Zionism went beyond mere verbal support. In December 1918, just a month after the end of World War I, Lawrence orchestrated a meeting between Arab leader Emir Feisal and Chaim Weizmann at London's Carlton Hotel. Acting as interpreter, Lawrence helped bridge the linguistic and cultural gap between them. Weizmann assured Feisal that Zionist development in Palestine would be expansive but not at the expense of Arab rights, stating that the country "could be so improved that it would have room for four or five million Jews, without encroaching on the ownership rights of Arab peasantry." Feisal, for his part, expressed surprise at reports of friction between Jews and Arabs in Palestine, noting that such conflicts were not common in other lands where the two peoples coexisted.

These initial talks led to a more formal agreement signed on January 3, 1919. Known as the Feisal-Weizmann Agreement, this document recognized the national aspirations of both Arabs and Jews. It essentially exchanged Arab support for the Balfour Declaration and Jewish settlement in Palestine for Zionist backing of an independent Arab state beyond Palestine's borders. Lawrence, again playing a crucial role, hoped this agreement would ensure "the lines of Arab and Zionist policy converging in the not distant future." Though the agreement had little long-term impact, it marked a rare bright moment in Arab-Jewish relations.

Looking back, Lawrence’s plan for Jewish-Arab cooperation in a revitalized Middle East appears naïve. In the early 1920s, he confidently told Churchill that “in four or five years under the influence of a just policy, the opposition to Zionism would have decreased if it had not entirely disappeared.”12 He even drafted a letter on behalf of Emir Feisal to Felix Frankfurter, a leading American Zionist, wishing the Jews “a hearty welcome home” and declaring that “our two movements complete one another.”13 In retrospect, it’s unlikely that even Feisal himself agreed with what the idealistic Lawrence wrote in his name.

It’s difficult to square Lawrence’s fantastical hopes for Jewish-Arab cooperation with his clear-eyed understanding of Arab culture. More than most of his contemporaries, he understood that the Arabs were not people of compromise or complexity. “[They] have no half-tones in their register of vision. [The Arabs are] a people of primary colors, or rather of black and white… a dogmatic people that… know only truth and untruth, belief and unbelief, without our hesitating retinue of finer shades.”14

In March 1921, Lawrence traveled with British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill to the Cairo Conference, where he played a critical role as Churchill’s Arab affairs adviser. Captain Maxwell Coote, Churchill’s Orderly Officer, later recalled a frightening moment from the conference: “[Lawrence and I] went up together with Mr. Churchill to Palestine… On the way we stopped at many wayside stations where Mr. Churchill was given vociferous welcomes. The first of these was at Gaza where there was a tremendous reception by a howling mob all shouting in Arabic ‘Cheers for the Minister’ and also for Great Britain, but their chief cry over which they waxed quite frenzied was ‘Down with the Jews’ and ‘Cut their throats.’ Mr. Churchill and Sir Herbert were delighted with the enthusiasm of their reception, being not in the least aware of what was being shouted. Lawrence, of course, understood it all and told me, but we kept very quiet. He was obviously gravely anxious about the whole situation… We finally got away from Gaza with a sigh of relief on the part of Lawrence and myself.”15

More than a century later, little has changed in Gaza, where Arab mobs are still screaming for the wholesale slaughter of Jews. Lawrence witnessed this with his own eyes, yet failed to see – or did not wish to see - that the Jews’ return to the holy land would inevitably conflict with the Arabs’ extremist ideology.

Vladimir Jabotinsky, the clear-eyed Zionist leader of the same era, dismissed the hopes of idealists like Lawrence as both childish and dangerously misleading. “To imagine, as our Arabophiles do, that [the Arabs] will voluntarily consent to the realization of Zionism in return for the moral and material conveniences which the Jewish colonist brings with him, is a childish notion, which has at bottom a kind of contempt for the Arab people; it means that they despise the Arab race, which they regard as a corrupt mob that can be bought and sold, and are willing to give up their fatherland for a good railway system.”16

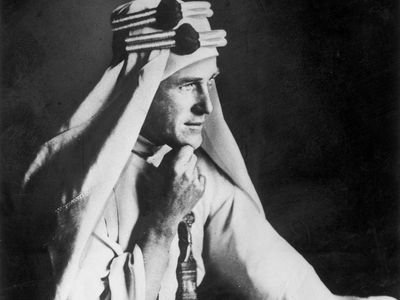

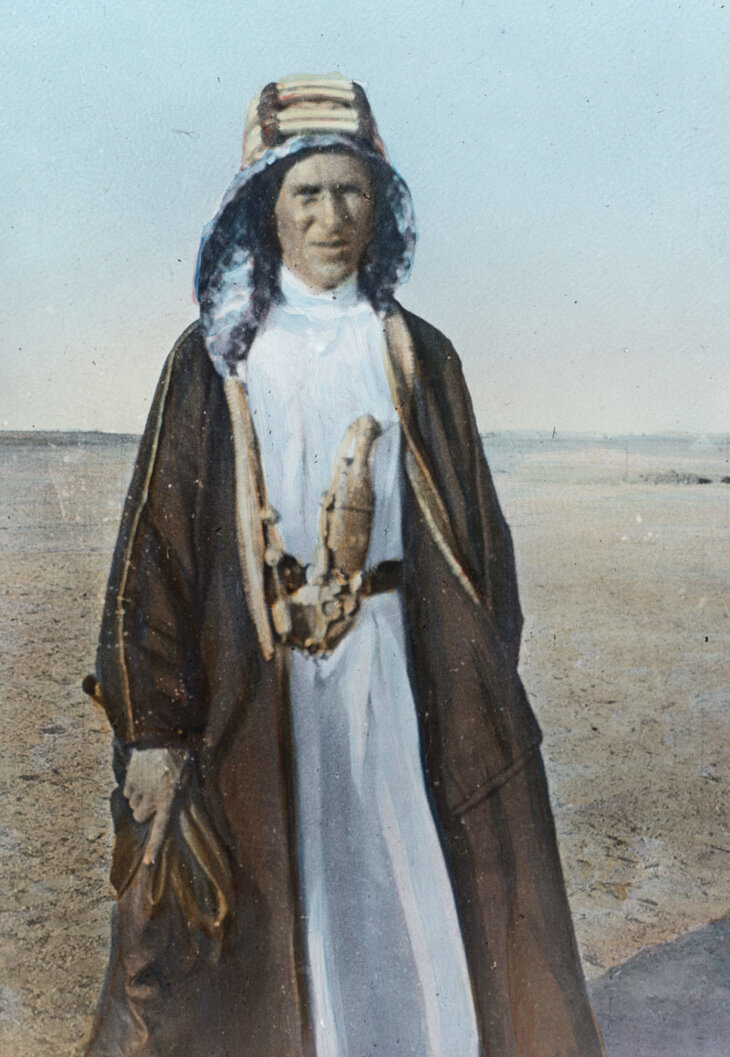

Lawrence in 1918

Lawrence in 1918

Decades of Arab wars and terrorism against the Jewish state have proven the truth of Jabotinsky’s words. While Jews accepted the UN partition plan in 1947, despite it allocating much of the land previously promised to them to the Arabs, Arab nations showed no interest in compromise. Instead, they immediately invaded the newly declared State of Israel, marking the beginning of an ongoing assault on the Jewish state that continues to this day. Efforts to improve economic conditions in Gaza, Judea and Samaria did little to stem the rise of Hamas and Islamic extremism among these populations.

Though his utopian vision of Arab-Jewish cooperation did not age well, there remains much that we can and must learn from Lawrence.

Edwin Samuel, son of Herbert Samuel, the first British High Commissioner for Palestine, spoke with Lawrence in the early 1930s. He asked him why some people were labelling Lawrence as an anti-Zionist. Lawrence said that this was nonsense, for he himself had invented the slogan “Arabia for the Arabs, Judea for the Jews and Armenia for the Armenians.” Samuel writes that Lawrence was very clear: he did not support any Arab claim to Palestine.17 By a Jewish state, Lawrence meant a Jewish state from the Mediterranean shore to the River Jordan.18

Tellingly, the great champion of Arab nationalism did indeed support a two-state solution, albeit one quite different from today's proposal. Lawrence envisioned an Arab state established on the eastern side of the Jordan River and a Jewish state – encompassing all of Judea and Samaria – on the western side. This original "two-state solution" was realized with the establishment of the Arab state of Jordan in 1946.

Lawrence, Emir Abdullah, Air Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond, Sir Wyndham Deedes, and others at the Jerusalem Colony Hotel, the 1921 Cairo Conference

Lawrence, Emir Abdullah, Air Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond, Sir Wyndham Deedes, and others at the Jerusalem Colony Hotel, the 1921 Cairo Conference

Lawrence was not alone in this view. On March 28, 1921, Lawrence, Churchill, and Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein - who would later become the first King of Jordan - met in Jerusalem. During this meeting, Abdullah agreed to limit his control to Transjordan and relinquish all Arab claims to the land west of the Jordan River, conceding that Judea was, indeed, the land of the Jews.

In 1929, Great Britain’s Conservative party was defeated at the polls and Winston Churchill found himself without political office. Lawrence presciently wrote: “He’s a good fighter, and will do better out than in, and will come back in a stronger position than before. I want him to be Prime Minister somehow.”19 Churchill would indeed become Prime Minister, but Lawrence tragically did not live to see it. In May of 1935, he died from fatal injuries he sustained in a motorcycle accident near his cottage in Dorset. He was only 47 years old.

A few years before his death, Lawrence discussed the challenge of Zionism with the Jewish historian Sir Lewis Bernstein Namier. With extraordinary foresight, he told Namier: “The problem of Zionism is the problem of the third generation. It is the grandsons of your immigrants who will make it succeed or fail, but the odds are so much in its favor that the experiment is worth backing.”20

As Lawrence presciently predicted, the future of the State of Israel is in our hands. We are the third generation, the grandchildren of the Zionist pioneers, who will determine whether Zionism succeeds or fails. As Arab enemies threaten Israel’s very existence, it is our turn to rise up and defend our people, to ensure “the everlasting miracle of Jewry” continues to inspire humanity for generations to come.

What Lawrence told Edwin Samuel, that he invented the slogan "Arabia for the Arabs" etc, is also highly dubious. This was either Lawrence blagging away or Samuel mis-remembering. Lord Robert Cecil, addressing the Great Thanksgiving rally in London on 2 December 1917, long before Lawrence showed any support for the Zionist cause, declared: "Our wish is that Arabian countries should be for the Arabs, Armenia for the Armenians, and Judea for the Jews".

I'm intrigued by this "western leaven" quotation, which gets repeated all over the place. The source Martin Gilbert gives - Jewish Guardian, 28 November 1918 - turns out to be incorrect. The Jewish Guardian didn't begin publication till October 1919, and was anti-Zionist. Gilbert's not always accurate on these matters, I find. And your footnote 8 here sends one off on a false trail. Did Lawrence ever actually say this, I wonder, or did Gilbert invent it to bolster his case?

first-class article. 3 things to note:

Lawrence's perception that the Arabs perceive no half tones, they see only black or white-- I.e., they don't how to compromise or share. how true. surely sound like today.

Jabotinsky's remark that one who says the Arabs will be peaceful if you improve their economy shows contempt for the Arabs. In my view, it's not contempt, it's naivite' and utopianism on the part of Lawrence.

Rudyard Kipling's condescension towards Lawrence, that if the latter showed himself to be "pro yid," he, Kipling, would not want to have anything to do with Lawrence. What a despicable view, and of course antisemitic.

I was unaware of Lawrence’s support for Zionism. I will get his book.

Did you know that Lawrence of Arabia favored a two-state solution for Palestine with Jordan on the east bank and what would become Israel on the West Bank?

Fantastic and enlightening article. I remember seeing the movie as a teenager. I was under the impression he was only interested in supporting the Arab cause. I had no idea about his understanding and support of Zionism. Of course, the British, to this day, don't support Zionism let alone Jews in the UK. Thanks for sharing this wonderful article.

his mission was to undermine the ottoman empire, and what better way to do that than to stir up trouble with the jews as well as the arabs.

Truly amazing and important information that I wish somehow would be distributed across the planet. Thank you. Kol ha kavod!

A fascinating, well researched and enjoyable read, that Lawance was also a Zionist does not suprise me. He really understood the region very well even if he was naive still in some respects. His book should be mandatory reading by all who want to be thier countries foreign secretary and have to deal with the middle east.Yes i do have a copy of it on my Kindle.

Great article. Toda.

Excellent

Wonderful, well-researched article; thank you!

Sad but not surprising to read that Arab mentality has largely remained stagnant in its hard core refusal to accept reality and negotiate for the betterment of its people's lives.

it’s way more than just mentality, it’s culture. the humiliation of jewish sovereignty will always be more important to them than their very lives - this isn’t going to change, so the best we can do is keep them away from “sharp objects”.

Wow, fascinating!