Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

6 min read

The appalling story of desecrated tombstones from the 16th century Sephardic cemetery of Ferrara, Italy.

The columns had graced the entrance to the Ducal court in Ferrara, Italy for 500 years. On the right, a miniature version of Rome’s Arch of Titus topped by an equestrian Marquis Niccolò III, and on the left, an unusual bichrome column upholding a representation of Borso D’Este, the Duke of Ferrara (1413-1471).

A noted patron of the arts, he and his immediate successors also made Ferrara a haven for Jews, especially those expelled from Spain and refugees from the Inquisition in Italian territories to the south. Under the House of Este, Jewish life flourished in Ferrara 1598, when the Papal States exerted control over the northern Italian city.

The Jewish badge was instituted shortly thereafter, and Ferrarese Jews who once lived and worked throughout the city found themselves shut in the confines of yet another Ghetto.

The 15th c. Palace of Ferrara with the Volto del Cavallo at the lower right, flanked by the columns of Borso d’Este (left) and the Marquis Niccolò III (right). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The 15th c. Palace of Ferrara with the Volto del Cavallo at the lower right, flanked by the columns of Borso d’Este (left) and the Marquis Niccolò III (right). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1960, the eccentric, mismatched columns – a major artistic feature of downtown Ferrara – were in desperate need of major restoration. The column of d’Este was especially complex: construction workers carefully labeled the rings of concentric grey stone that tracked up much of the column, in preparation for removing them from the structure.

Left: Restoration workers labeled the stones before dismantling the column (1960). Source: Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica. Right: The column of Borso D’Este

Left: Restoration workers labeled the stones before dismantling the column (1960). Source: Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica. Right: The column of Borso D’Este

When they dismantled the column, they were in shock by what they saw. Freed from the column, the stones revealed their true identities as Jewish tombstones, covered in Hebrew script.

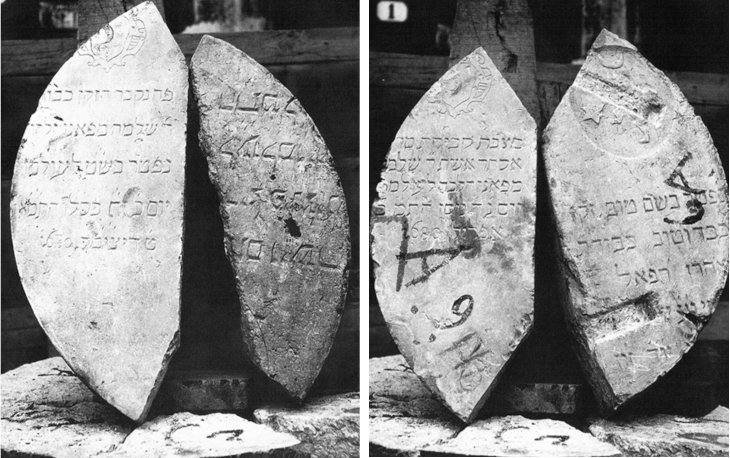

Fragments of Tombstones. Far Left, the marker for Ester the wife of Shlomo of Fano (d. April 1680). Right of middle: grave of Shlomo of Fano (d. December 1680) Source: Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica

Fragments of Tombstones. Far Left, the marker for Ester the wife of Shlomo of Fano (d. April 1680). Right of middle: grave of Shlomo of Fano (d. December 1680) Source: Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica

Thirty-six fragments of desecrated tombstones were sliced and carved to fit the dimensions of the column. Piecing together the inscriptions, scholars identified that they belonged to members of the Ferrara Jewish community who died between the years 1577 and 1690, such as Rabbi Shlomo of Fano and his wife Esther, who died within months of each other in 1680.

Piecing together the inscriptions, scholars identified that they belonged to members of the Ferrara Jewish community who died between the years 1577 and 1690.

How and why did these tombstones get built into the column of Borso d’Este?

The “why” is easily understood: on a practical level, the grave markers were carefully measured and dressed, quarried for their strength, durability and beauty. Removed from their original holy sites, they would have represented a significant, albeit reprehensible, shortcut for the builders.

The question of “how,” on the other hand, remains something of a mystery to this day.

The column was first erected in the 1450s, and it had stood for over 200 years before it was heavily damaged by a fire on 23 December 1716. A chronicler of the period, Nicolò Baruffaldi, mentions that Marquis Francesco Sacrati secured the stones from the Jewish graveyards, “paying in full for their value to the Masters of the Ghetto," It is highly unlikely that the Jewish community would have willingly surrendered the gravestones of their ancestors, especially noting that many of the graves belonged to people the contemporary Ferrarese Jews would have actually known – the grandparents and even parents of the generation alive at the time.

Coat of Arms from a Tombstone Fragment. Source: Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica

Coat of Arms from a Tombstone Fragment. Source: Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica

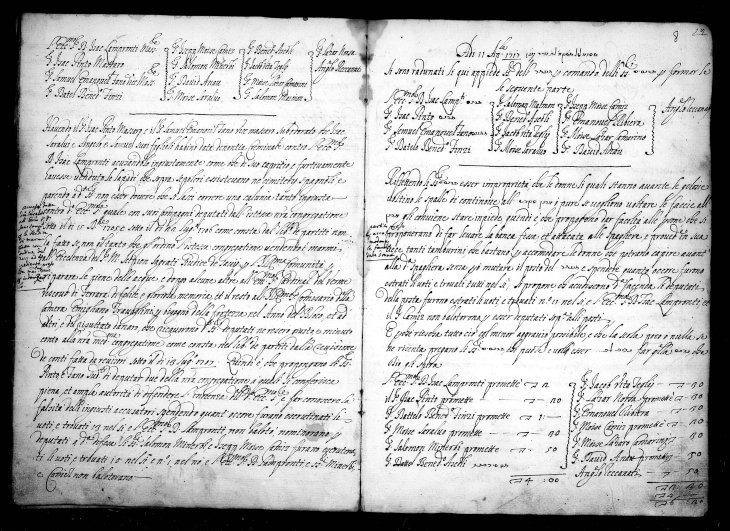

The communal record book, or Pinkas, of Ferrara for that period is unfortunately lost, but records from just a few years later convey a huge controversy that swirled around the use of tombstones for repairs connected with flooding caused by the Po river. Many claimed — reasonably — that they were illegally confiscated from the Sephardic community of Ferrara, while their purchasers maintained that they were properly bought and paid for.

Among the customers for the stones was the local Bishop, Taddeo Luigi Dal Verme, who had earlier issued an edict banning the marking of Jewish graves with new gravestones altogether, as if to eliminate the presence of their dead from the city. As for the 16th and 17th century stones acquired by the Bishop — the pinkas asserts that they were used to pave the stable for his horses.

The entry dated April 8, 1717 from the Communal Record Book (Pinkas) of Ferrara.Source: National Library of Israel.

The entry dated April 8, 1717 from the Communal Record Book (Pinkas) of Ferrara.Source: National Library of Israel.

During the 1960-61 restoration, the gravestones were photographed, preserving the historical record. Amazingly, they were not returned to the Jewish community, they were rather put back into the column where they remain to this day. In fact, they were desecrated still further, with pieces removed and discarded to make room for a reinforced concrete core to protect the column from seismic activity (a devastating earthquake had hit Ferrara in 1570, which Pope Pius V blamed on the Este family for their historic protection of the Jews).

Reconstructing this tragic history has become the task of younger historians like Dr. Antonio Spagnuolo of the University of Bologna, dedicated to researching the fate of the lost tombstones of the Jewish community of Ferrara. His work has focused on key sources such as the Community Archives, now held in the National Library of Israel, but he notes that the silence of the Jewish community when the stones were discovered in 1960 remains are an added mystery. With few documents that describe the particulars of the restoration work, it is possible that the small post-war Jewish community of Ferrara was simply not alerted to their existence, or perhaps did not have the wherewithal to protest effectively.

Dr. Antonio Spagnuolo of the University of Bologna

Dr. Antonio Spagnuolo of the University of Bologna

And so the gravestones remain to this very day entombed, not in sacred space, but in the monumental column dedicated to the memory of an Italian Duke.

Yet the sad story is not without a degree of historical, poetic irony. The Duke Borso D’Este himself had nothing to do with the desecration of the tombstones — his statue was erected 250 years before the markers were used to reinforce the column. On the contrary, the House of Este was known for its uncommon record of kindnesses rendered to the Jewish minority.

Now, nearly 600 years later, the Ferrarese Jewish community continues to uphold his memory – literally – with the stones of their ancestors supporting the monumental column of the Volto del Cavallo.

For further reading:

Antonio Spagnuolo, “Were the ancient headstones sold or stolen and who was responsible for their disappearance?” The Librarians (National Library of Israel blog)

Antonio Spagnuolo, “Il riutilizzo della stele funerary dei cimiteri ebraici sefarditi di Ferarra nel pinqas della scuola spagnuola degli anni 1715-1811,” Materia Guidaica XXIII (2018),

Paolo Ravenna, Le lapidi ebraiche nella colonna di Borso d'Este a Ferrara (2003)

Flavio Baroni, Ferrara Ebraica: Le lapidi israelite nella colonna di Borso d'Este (2018)

L. Sirovich, and F. Pettenati (2015), Source inversion of the 1570 Ferrara earthquake and definitive diversion of the Po River (Italy), J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth, 120, 5747–5763

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/2015JB012340