Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

9 min read

And the arduous road it took to persuade the U.S. government to save them.

It was summer 1944. The U.S. had just landed in Normandy and the fight to push back the Nazis had begun. It was nearing the end of the war, but to Europe’s Jews there was no end in sight. The Final Solution was in full swing, deportations to death camps were increasing, hundreds of thousands of lives ruthlessly murdered week by week, day by day (about five million Jews were already murdered by this time).

The shadow of the Nazi regime clung to its power and to its vow to rid Europe of its Jews. And the world had fallen silent to the cruelest, most systematic genocide of all time.

That August, freedom was finally in reach for 982 lives.

Two months earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had reluctantly signed an agreement allowing up to 1,000 refugees to take refuge on America’s soil. A few weeks later, the S.S. Henry Gibbins set sail from Naples, Italy carrying 982 passengers (about 900 of them were Jews) to the United States. Upon arriving in New York Harbor in early August, tears of relief and joy overwhelmed the worn-out passengers on the fateful ship - they were safe. They were of the few lucky souls who made it out.

However, the refugees were not to set foot on New York City soil. At the harbor, they were medically screened, put onto trains and sent immediately upstate to Fort Ontario, located in a small town called Oswego, New York. Unaware of where they were being sent, an unsettling yet all-too-familiar feeling swept their minds.

The city soon faded away into the abyss and the mountains and hills of rural upstate New York surrounded the horizons. The train finally reached its destination on August 5th, 1944, only to deepen their fear.

Ben Alalouf, a Jewish refugee from Yugoslavia, recalled the sheer fear of his parents when they came to the refugee camp and saw barbed wire surrounding the encampment they were to enter. Although he was a small child at the time, he remembered their panic. “Everyone thought it was a concentration camp,” he said. Had they been deceived?

Soon enough, the refugees realized their fears were misplaced. Here, they lived in freedom (within the borders of the refugee camp), they befriended the local community, and were able to establish a synagogue and practice Judaism freely. Despite not being allowed to explore the country around them, the refugees no longer had to fear for their lives. The nightmare of a world from which they came was in the past.

Still, the specter of returning to Europe loomed overhead. The United States government, in order to garner enough support from the U.S. public, had forced the refugees to sign a contract claiming that upon the end of the war, they were to return to Europe. But who knew when that was to be? More importantly, where were they even to return to? Having been uprooted from their homes, persecuted for their identity, they were truly displaced people whose homes were ripped from underneath them. Was the United States really going to send them back to a place that drove them out?

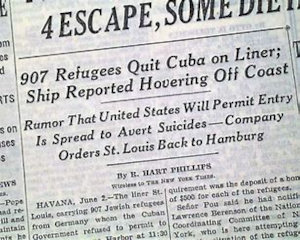

The U.S. is known for the little they did to aid Jewish refugees throughout the war: from the Evian Conference in 1938 where around 30 countries, including the United States, met to discuss the impending doom on European Jewry yet did nothing about it; to the S.S. St. Louis in 1939 where over 900 Jewish refugees were turned away from Cuba and then, to their humiliation, from the United States after sailing up the Miami coast for 12 days; to the countless bills in the early 1940’s calling to take in refugees that were simply dropped in congress. Time after time, opportunities came up to help, and the American government scarcely lifted a finger.

The quota system for refugees in America was abominably low from the post-World War I era, when the public felt there were already too many immigrants (many being Eastern European Jews) entering into the country. This anti-immigrant/refugee sentiment carried through to the 30’s and 40’s, thereby blocking entry to millions of Jews in dire need of safety. Roosevelt, amongst other politicians, were in no rush to change this policy, even amidst the wake of the war.

Some notable exceptions were John Pehle, U.S. Department of Treasury lawyer, and Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Secretary of Treasury. Pehle worked tirelessly to save Jewish refugees by communicating with other politicians and Jewish organizations to come to an actual agreement in bringing them to safety. In February 1944, he devised a detailed plan to bring refugees to the Virgin Islands, but met resistance when proposed to FDR’s War Refugee Board (WRB), which was ironically created to aid victims of the Nazis.

U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson, who was part of the WRB, told Pehle that the American public would object out of “fear that the location of so many Jews in this country would become permanent after the war” and that it was “almost impossible to ensure that they [Jews] would be taken back” post-war. These objections convey the level of antisemitism and xenophobia that had been prevalent among the American population and the government during that period.

Upon receiving this response, Pehle drafted a new plan. He offered various places across the country that could house refugees, detailing costs, food, and more. Here, Morgenthau allied with Pehle to influence other politicians to agree to the plan as well.

At the same time Pehle was developing his plan and lobbying to FDR’s administration in the first half of 1944, an editorial in the New York Post, written by Samuel Grafton, was published, advocating for free ports as a way to admit refugees. The public support from those who wanted to help save lives was astounding.

Alongside this article, Peter Bergson had started demonstrations against the Nazi atrocities toward Jews (which were public knowledge by 1942) and he got 3,000 leading Americans, including Senators and Representatives, to sign a petition condemning this. These voices gained attention in media outlets and spread to the public eye. The push to allow entry to the poor refugees grew, which was brought to the attention of the president. It seemed as though there was a political shift - anti-refugee sentiments were changing.

It took months of negotiations, partnered with time-wasting trepidation and hesitation, but FDR finally agreed to admit 1,000 refugees to Fort Ontario in Oswego, NY. After seeing the public response to the NYT article about free ports, FDR perhaps took this shift in public perspective as a sign that admitting refugees was a beneficial political move. As Josiah Dubois, Jr., a member of the WRB, said about FDR, “Roosevelt was a politician first, and then a humanitarian.”

To put the urgency of the situation combined with the lack of action into perspective, let’s take a look at the mass deportations of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz in 1944. By early May, mass deportations to Auschwitz became systematic, and by June 7th, which was right before FDR officially established the refugee camp in Oswego, approximately 290,000 Jews were deported. Nearly 520,000 more Jews would be sent to their deaths over the next month, before the S.S. Henry Gibbins even left Italy’s shore. Who knows what could’ve happened, or who could’ve been saved if the government had acted quicker, had opened more ports, or had put humanity over politics?

In the end, over 3,000 people applied for visas, and only 1,000 were accepted (only 982 were present at the time of boarding). Approximately 90% of the refugees were Jewish, some having had experiences in Dachau and Buchenwald, some having hidden for many months, trekking across the Alps or sailing in rickety boats across the Adriatic for safety, and all trying to escape the trauma of having a target on their backs for their identity.

Once the refugees were settled into Fort Ontario, life in the refugee camp was no breeze. Although safe and secure, the traumatic reality of what many of these people had been through was not left behind. The inability to explore their surroundings, and the unknown of the future prevented a sense of instability which caused anxiety.

Upon the passing of FDR in April 1945, the refugees had higher hopes of being able to lobby to the new government to stay in the United States. They wrote to President Truman asking for immigration papers. Again, negotiations continued for months while the refugees remained in the camp, waiting for a decision from the American government on what was to become of them.

One politician, Joseph Chamberlain, voted for sending the German Jews back to Germany, justifying his perspective by claiming that “Jews have just as good a position in Germany and are as well treated as anybody.” This was said in September, 1945, only a few months after VE Day, and after the full realities of the atrocities of the Holocaust were public news. In one short statement, Chamberlain chose to invalidate the fear and the anxiety of going back after history’s worst genocide.

It wouldn’t be until the spring of 1946 that a decision would be reached, and the refugees would be granted legal papers to enter the United States as citizens.

The Truman Administration found a loophole that would grant the refugees the ability to enter the United States as legal immigrants, and not as refugees. In order to do so, the refugees were put onto busses to Canada, given immigration papers, and crossed back over the border into the United States with their papers. From there, they were relocated to housing in cities across the United States.

This sliver of Holocaust history speaks volumes. For one, it is the sole attempt by the United States to provide a haven for refugees during the war. Not only that, it conveys the hardships Jews faced to be accepted not only in Europe, but in America, the land of the free. It reflects the hesitation the world had to help Europe’s Jews, knowing full well what was happening, and it questions the resolve of humanity to put the ethical over the political, even in the most desperate of times.

The site of the refugee camp is still standing and you can visit the Safe Haven Museum in lake-side Oswego, New York. Safe Haven Holocaust Refugee Shelter Museum | Fort Ontario | Oswego New York (safehavenmuseum.com)

Bibliography: