Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

8 min read

The world’s most popular doll has a long Jewish history.

In Greta Gerwig’s upcoming movie Barbie, the doll heads out into the real world with her beau Ken on a life-changing adventure washed in pink.

This ubiquitous plastic doll – with her mountains of accessories, from clothes to cars and even houses – enjoys annual sales in excess of $775 million. Barbie continues to be in the news: a new version of the doll with Down’s Syndrome, debuted in April 2023, has been a huge hit.

The new Barbie with Down’s syndrome

The new Barbie with Down’s syndrome

Yet much of Barbie’s history - and the Jewish influences on the toy - remain little known. Here are five Jewish facts about Barbie.

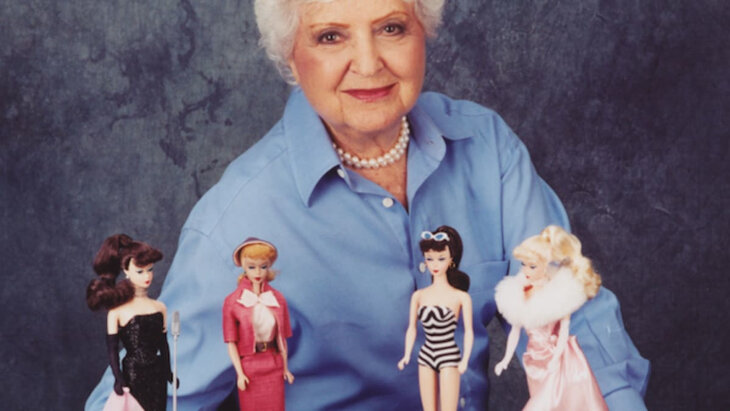

When Barbie’s inventor, Ruth Moskowicz, was born in 1916, her family was finally settling down after years of upheaval. Ruth’s father Jacob was from the Russian Empire, and like many Jews in Czarist Russia, had been drafted into the army. Jews were forced to serve for 25 years, far longer than other conscripts.

Jacob escaped from his unit and boarded a ship bound for America. A talented ironsmith, immigration officials suggested Jacob settle in Denver, where his skills could help build the new railroads. After years of work, he was able to bring over his wife and seven children from Poland. Ruth was born in Denver, their tenth and youngest child.

Ruth and Elliot Handler

Ruth and Elliot Handler

Ruth met her husband Elliot Handler – another child of Russian Jewish immigrants – at a Jewish dance when they were teenagers. They eventually moved to Los Angeles and experimented with building furniture out of the new plastics that were being invented at the time. Ever the hard-nosed businesswoman, Ruth worked as an equal partner with Elliot.

When Elliot was drafted during World War II, Ruth worked to sell plastic items she and Elliot designed under the auspices of their new company, Mattel. After the end of the war, Ruth and Elliot began to shift their manufacturing focus to plastic toys, tapping into the newfound prosperity of peacetime.

While Ruth and Elliot weren’t traditionally observant, their Jewish identity was always central in their lives. As Mattel’s success grew, the Handlers became major philanthropists in Los Angeles, supporting an array of both Jewish and secular causes. “That was our training, our background,” Ruth explained; “the Jewish ethic.”

In her book Barbie and Ruth: The Story of the World’s Most Influential Doll and the Woman Who Created Her (2009), author Robin Gerber describes Ruth’s reaction to the start of the Six Day War in Israel in 1967. Ruth had always been a large donor to the United Jewish Appeal in Los Angeles; when war was declared, she phoned them up and asked what she could do to help. The phones were ringing off the hook, the person answering replied: could she please come down to the UJA offices and help field phone calls?

Ruth, the president of Mattel, one of the largest companies in the US, had an incredibly busy schedule, yet she dropped everything and raced downtown to field phone calls. Within days, she’d set up an efficient system of answering calls and accepting donations from people who wanted to support Israel’s war effort and returned to Mattel. “That’s what I call public service,” she described. “I felt very good about it.”

Barbie’s genesis came one afternoon as Ruth Handler watched her young daughter, Barbara, and her friends playing with paper dolls.

In the 1950s, toy companies primarily made baby dolls for girls to play with. It was naturally assumed that all girls aspired to feed and bathe a tiny baby, and nothing more. There were a few older-looking dolls for sale, but these often looked like giant versions of babies, and were more grotesque than glamorous. It took a Jewish mother to observe real-life girls and see that they wanted something more.

Barbara and her friends cut out paper dolls from McCall’s magazine and dressed them in delicate paper outfits. Then, they each held up their dolls and made them talk, imitating adult conversations. “I knew that if only we could take this play pattern and three-dimensionalize it, we would have something very special,” Ruth Handler later described.

In 1956, the Handlers took a long summer vacation to Europe, and Ruth found the sort of doll she’d dreamt of creating: a German “Bild-Lilli” doll. In the 1950s, these were popular joke gifts across central Europe. Bild-Lilli grew out of an off-color newspaper cartoon in the Bild-Zeitung newspaper, and there was something intensely seedy about the dolls, which were meant to be adult gag gifts given on occasions like bachelor parties. Despite this troublesome connotation, the dolls were well made and came with beautiful clothes. And little girls loved them.

Ruth bought a few to take back home with her. When she suggested creating something similar, her Japanese suppliers were aghast, protesting that the dolls looked inappropriate for children. Ruth changed the features, creating a more wholesome-looking doll.

This new doll - dubbed Barbie after Ruth’s daughter Barbara - was so different from anything else in the American market, Ruth wanted to proceed very cautiously. She turned to Dr. Ernest Dichter, another Jewish innovator, a psychotherapist from Vienna who’d fled Hitler and moved to New York, for help.

Back in Vienna, Dr. Dichter used to see patients in his office which was across the street from Dr. Sigmund Freud’s. In the United States, he gave up practicing medicine and became an early pioneer of what he called motivational psychology, and what today is more commonly called marketing. Dichter’s genius was in asking consumers detailed questions about what they wanted and how they thought about different products. Previously, it was more common for company chairmen to guess what their customers were looking for.

Dr. Dichter leapt at the chance of working with Ruth Handler on Barbie. The field of marketing to children was in its infancy and the adult-looking doll that Ruth wanted to sell was highly unusual. Critics complained that it was inappropriate to give girls adult-looking Barbies. (If Barbie were scaled up to human-sized, she wouldn’t be able to stand up on her undersized feet, and would be severely malnourished.) Yet the prototypes were hits with girls.

Dr. Dichter interviewed 191 girls and 45 mothers. He found that the mothers uniformly hated the Barbie prototype they were given to review, but the girls loved it. They embraced the adult-looking doll and acted out their own imagined futures while they were playing. Dr. Dichter advised Ruth not to market Barbie as a doll, but as a natural extension of girls’ self-expression. Barbie became one of the first toys advertised on television and the term “doll” was barely used.

Launched in 1959, Barbie caught on like wildfire. Girls reveled in their new ability to create glamorous make-believe worlds using their new toys. The dolls were unapologetically girls-centric. Mattel launched a male doll named Ken (named after the Handler’s son) in 1961, but he got second billing. In the world of Barbies, girls were allowed to envision adult life with women firmly in center stage.

Ruth and Elliot Handler often credited their immigrant Jewish background with rendering them open minded. Having experienced antisemitism, they were determined to see others for who they were, instead of through the prism of harmful stereotypes.

From its beginnings in the 1940s, Mattel resisted the racial segregation that was the norm in other American factories. The Los Angeles Conference of Community Relations wrote a letter to Mattel in the 1940s, noting that “A tour of your plant is like walking through the United Nations. People of different races, various religious faiths, handicapped people, elderly people, all working as a unit. You have set an example that might well be followed by business people everywhere.”

In 1968, Mattel released a Black doll named Christie who was billed as Barbie’s “best friend”, and launched another Black doll named Julia the following year. The company released their first Black Barbie in 1980. Today, Mattel sells over 170 different types of Barbie, with varying skin tones and hair colors, allowing children to find a Barbie doll who looks very much like them if they choose.

Ruth Handler passed away in 2002; Elliot Handler died in 2011. Their company Mattel went public in 1960. Yet in some quarters, Barbie is still seen as an intensely Jewish toy.

It’s been banned in Kuwait since 1995. Iran tried banning Barbie the following year, and launched their own “Islamic” dolls that they encouraged Iranian girls to play with. After a few years, officials abandoned their efforts to stop the sale of Barbie dolls in the country. Barbie was banned in Russia in 2002 by President Vladimir Putin, who accused the doll of being Western. In 2003, Barbie was banned in Saudi Arabia for being “Jewish”; Saudi Government officials describe the toy as “Jewish Barbie.”

Yet even in places where it is banned, Barbie dolls are often available for purchase on the black market. Ruth Handler’s creation touches something deep inside girls, as they navigate the world around them through play. There’s much to criticize, including Barbie’s impossibly perfect-looking figure and overly thin physique. But Barbie also allows girls to act out their dreams of becoming women.

With robust sales, an ever-increasing number of variations, and a highly anticipated feature film, Barbie – drawing on her Jewish past – has a very bright future.