The Irrationality of Antisemitism

The Irrationality of Antisemitism

10 min read

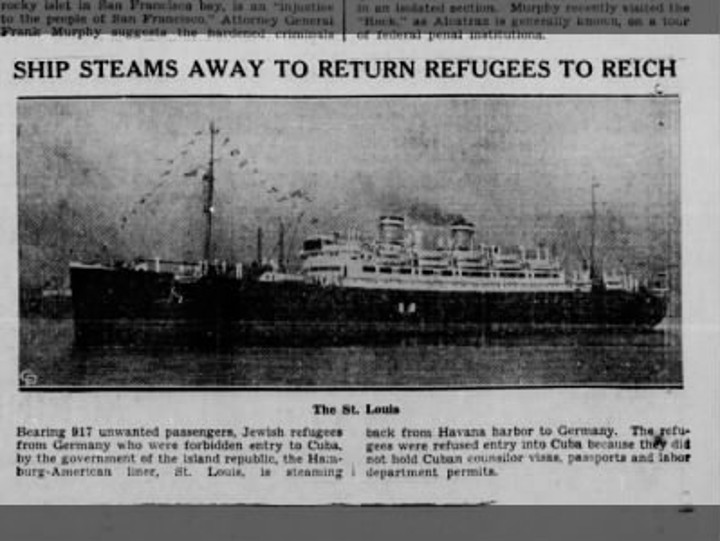

The ship set sail with over 900 Jewish refugees and was rebuffed by the United States and Canada.

During World War I, Max Loewe was a hero fighting for his country Germany and earning the coveted Iron Cross. Twenty years later, like Jews across Germany, he found himself in a very different country. Under Nazism, Jews were barred from virtually all professions and forbidden even to set foot into many public spaces.

In 1937 German authorities had built the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp near the picturesque German town of Weimar. At first primarily political dissenters found themselves imprisoned there, and in 1939 Jews began to be sent to the prison camp where they received brutal, often fatal, treatment at the hands of sadistic guards. Max Loewe was one of the many thousands of Jews sent to Buchenwald. He was beaten so severely by guards that afterwards he walked with a pronounced limp.

Max was released from Buchenwald and he and his wife desperately tried to find a way out of Germany. By 1939, only wealthy Jews could leave: they had to pay a steep fee to leave the country, and high payments to other countries that might be willing to offer visas to let them in.

Many Jews yearned to go to America but the 1924 Immigration Act set firm limits on the number of immigrants who could be admitted annually. In 1939, the number from Germany was 27,370, and it was filled almost immediately. Public sentiment in the United States was firmly against letting in Jewish refugees. A Gallup poll taken in November 1938, two weeks after Kristallnacht asked Americans “Should we allow a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live?” 72% answered no.

Other countries also refused to take in large numbers of desperate refugees. In Britain, the notorious 1939 White Paper limited Jewish immigration to Palestine to just 75,000 over five years. One by one, the nations of the world shut their doors against the Jews.

One marked exception was Cuba. The island nation allowed tourists to visit without a visa. Cuba’s corrupt director of immigration, Manuel Benitez, however, began issue “landing permits” to visitors that looked like visas. It was a money-maker for him and gave assurance to hundreds of desperate Jews that Cuba would allow them to visit, escaping the horrors of Nazi Germany. Max Loewe was one of the many Jews to obtain one of these so-called “Benitez visas”.

Hundreds of other Jews were allowed to leave Germany on the condition that they pledged never to return. They agreed to draconian terms that if they were ever to come back to Nazi Germany, the would be thrown into a concentration camp once more.

Over 900 Jews, including Loewe and his wife, booked passage on the cruise ship MS St. Louis, departing from Hamburg in Germany and destined for Havana. The ship was a luxury liner but virtually none of its passengers were taking a vacation. Virtually all of the 937 passengers on board were Jewish refugees. On May 13, 1939, the ship set sail with great fanfare. A band played and friends and relatives lined the shore, waving goodbye. The passengers watched as their homeland became a small dot on the horizon.

Before setting sail, Captain Gustav Schroder called a meeting with his 231-member crew, explaining that the passengers were all paying guests and were to be treated with the utmost dignity, even though they were Jews. He ordered the large portrait of Adolf Hitler taken down from the ship’s Grand Salon so that his Jewish guests would feel more comfortable.

That night, Cpt. Schroder recorded in his diary: “There is a somewhat nervous disposition among the passengers… Despite this, everyone seems convinced they will never see Germany again. Touching departure scenes have taken place. Many seem light of heart, having left their homes. Others take it heavily. But beautiful weather, pure sea air, good food, and attentive service will soon provide the usual worry-free atmosphere of long sea voyages. Painful impressions on land disappear quickly at sea and soon seem merely like dreams.”

For two weeks, the passengers enjoyed the sensation of freedom that had eluded them so long back in Germany. Alice Oster, who was in her 20s during the journey, recalled the thrill of hearing an orchestra play Strauss, something denied to Jews in Germany.

They didn’t yet realize that the “Benitez visas” that virtually all of the St. Louis’ passengers held were worthless.

Unbeknownst to the Jewish passengers, anti-immigrant and anti-Jewish feeling was running high in Cuba, and the authorities were under intense pressure to stop allowing Jewish refugees to settle in the island. An anti-Jewish rally in May drew 40,000 Cubans, the largest crowd ever assembled in the country. On May 5, eight days before the St. Louis even set sail, Cuba’s President Frederico Laredo Bru stopped honoring Benitez’s landing rights. They didn’t yet realize that the “Benitez visas” that virtually all of the St. Louis’ passengers held were worthless.

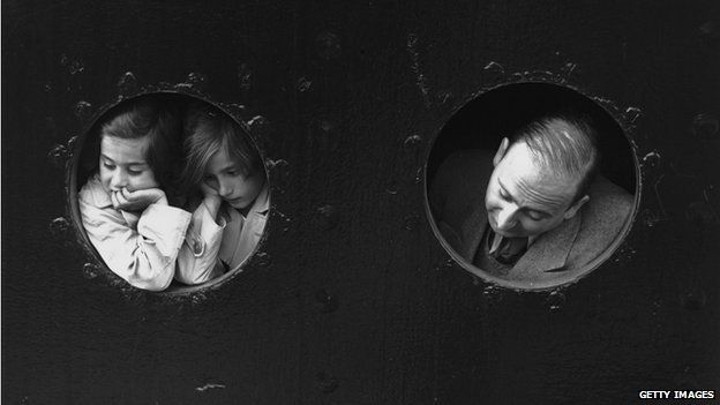

Early in the morning on May 27, 1939, bells rang out on the St. Louis alerting passengers that they’d arrived in Cuba. At first, nobody was worried about the fact that instead of pulling up to a dock, the ship was anchored in the middle of the harbor. By afternoon, however, Cuban police officers stood guard at the harbors piers and the passengers began to realize something was horribly wrong.

Later on, Cuban officials boarded the ship and marked the refugees’ passports with a big “R” for return. The passengers panicked. Many had relatives already living in Cuba and their worried friends and relations chartered boats to come up to the St. Louis so they could shout messages at the passengers trapped on board. Four Spanish citizens and two Cubans were allowed off, as well as 22 Jews who had full Cuban visas enabling them to settle permanently on the island. For the over 900 Jews without the right papers, Cuba seemed like a distant dream.

Liesl Joseph Loeb, who travelled on the St. Louis as a child, later recalled the passengers’ despair: “At the time we were in the harbor of Havana and things just weren’t moving along. We had some suicide attempts, and there was near panic on board because...many of the men all had to sign they would never return to Germany and if we had returned to Germany, the only place where we would have ended up was in a concentration camp because we had no homes left. We had no money left and we had nothing left… The world just didn’t care.”

One of those passengers contemplating suicide rather than go back to Germany was Max Loewe. On the night of May 30, 1939, while the St. Louis was still docked in Havana’s harbor, he slit his wrists then jumped overboard. Miraculously, he was fished out of the water by another passenger who jumped in after him and was rushed to the Calixto Garcia Hospital in Havana, the only visa-less Jew to reach Cuban soil.

A group of passengers formed a committee to negotiate with the Cuban authorities, and a representative of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee travelled to Havana to offer President Bru funds if he would take in the refugees. For a while, it seemed that Bru might accept money in exchange for the Jews. The Joint Distribution Committee had offered $125,000 to accept the Jews. President Bru insisted he wanted four times that, then broke off negotiations abruptly, declaring he would not allow the refugees to disembark.

Cpt. Schroder didn’t want to give up. Instead of steering his ship back towards Germany, he headed north, to Florida. He anchored off the coast of Miami, hoping that negotiations could continue and that America would agree to take in his passengers.

The St. Louis passengers went into action. The ship’s children mailed stacks of letters to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt begging her to take them in. The adult passengers sent a telegram to President Roosevelt reading “Most urgently repeat plea for help for the passengers of the St. Louis. Mr. President help the nine hundred passengers among them over four hundred women and children.”

American newspapers covered the plight of the St. Louis extensively. Many noted that the ship was running low on food and water. Hollywood stars sent telegrams to Pres. Roosevelt urging him to accept the refugees, to no avail. The only official response from the US Government was to send Coast Guard ships and airplanes to follow the St. Louis to make sure it didn’t make landfall.

Cpt. Schroder continued to try and find local islands in which to dock, but his search proved fruitless. For a while it seemed that the St. Louis might be allowed into the Dominican Republic, or into an island off the coast of Cuba. But he was never given permission and finally, on June 7, he started travelling - slowly and circuitously to prolong his journey - back to Germany.

The Joint Distribution Committee continued to work feverishly to prevent the passengers from returning to Germany. On June 13, with the St. Louis still at sea, they announced a deal. The Committee had pledged $500,000 to four countries, and in return the Governments of Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium agreed to take in the refugees. The ship was nearly back in Europe, and the passengers felt they’d had a sudden reprieve from near-certain death. Instead of Nazi Germany, they would surely now be able to build new lives elsewhere. On July 17, the St. Louis docked in Antwerp; from there the passengers were sent to their new homes.

England agreed to take in 287 refugees. One of these was Max Loewe; once he’d recovered enough to travel, he was forced to leave Cuba and moved to Britain. France took in 224 passengers, Belgium took in 214 and the Netherlands took 181. The refugees had no way of knowing that soon most of these countries would be part of the Third Reich and their Jewish communities destroyed.

The passengers of the St. Louis weren’t entirely typical of European Jews, and their survival rate was higher than for many of their compatriots. Many had relatives abroad and some were able to receive visas to other countries. 87 of the original passengers were able to emigrate out of Europe before Germany took over most of the continent in 1940. Virtually all of the passengers resettled in Britain survived the war, and they were aided by the American Joint Distribution Committee financially so they did not become a burden on the state. However the passengers forced to live in France, the Netherlands and Belgium faced the full fury of the Nazi killing machine. 254 St. Louis passengers were murdered in the Holocaust, most in Auschwitz and Sobibor.

My grandfather lived in Vienna and was only able to escape Nazi Europe after going into hiding in 1940. He was in Germany in July 1939 when the St. Louis was forced to return to Europe and he always used to tell me that was the worst day of his life. He listened to Hitler on the radio, ranting and raving that it wasn’t just him, it wasn’t only Nazis, who hated Jews. “See, the whole world hates the Jews” my grandfather recalled Hitler screaming.

Knowing that the St. Louis with its cargo of over 900 Jews had been rebuffed, not only by Cuba and the Dominican Republic, but by the United States as well, my grandfather, for the first time, felt that the whole world was indeed turning its back on Europe’s Jews.

…this is just unreal.

Hardworking, honest citizens that tried to it right.

All the paperwork, arrangements.

Paid (much) for those worthless ‘Benitez Visas’.

Grateful people that would have most certainly enhanced those Cuban communities with healthcare, education, industry.

Hope Benitez was somehow made accountable, at least for the huge total of funds he stole.

May he suffer and burn eternally.

And…Roosevelt? omg..never knew of this horrible decision/event.

My parents, Grandparents didn’t like or respect that Pres. I never knew specifics of why.