Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

8 min read

The famous antisemitic publisher of The International Jew was actually onto something mysterious about the Jews.

Today, there is a new brand of Jew-haters who claim that “Jews control Hollywood!” “Jews control the press!” “Jews control the banks!”

While Jews don’t control them, they are unquestionably well represented in those fields. Music, art, medicine, science, law, literature, and economics—Jews are disproportionally represented there as well. Is there a notorious cabal at play whereby Jewish people by the millions are involved in a conspiracy to control the world?

There was one man who thought so.

The International Jew, the four-volume, virulently antisemitic tract, written and self-published by Ford Motor Company founder, Henry Ford Sr. in the early twenties and said to have inspired Adolf Hitler to write Mein Kampf, is partly true. And though I’m sure it wasn’t the intention of the author, I must tell you, the ‘partly true’ part of the book left me feeling prouder to be Jewish than anything I’ve read since… well, perhaps since Leon Uris’s Exodus.

It’s a well-established idea in Judaism that nothing can exist if it doesn’t contain at least a modicum—some homeopathic dose—of pure truth. This past summer I spent a Shabbat at a friend's house in Minneapolis and it was by complete surprise that I happened on that bit of truth. As they often do in the northern latitudes of Minnesota, that mid-July Shabbat day seemed like it would never end. Sometime around 7:00 p.m., with the sun still high on the horizon, I discovered a dog-eared copy of The International Jew high up on a crowded bookshelf. I grew up in Minnesota, a place that for all its liberal leanings, was the original home of the National Socialist Movement in 1974. Knowing this fact, and having felt acutely the effects of antisemitism as a boy, I was curious about the book’s contents.

Ford used his money and influence to propagate his antisemitic worldview.

For historical context, imagine what it might have felt like to be Jewish if Apple founder, Steve Jobs, had used his economic power and social standing principally to spread Jew-hatred. Like Steve Jobs, Henry Ford was wildly popular and a much-beloved figure among most Americans at the time The International Jew was first published. And imagine if Steve Jobs had written a similarly antisemitic screed and put a copy of it on every new iPad.

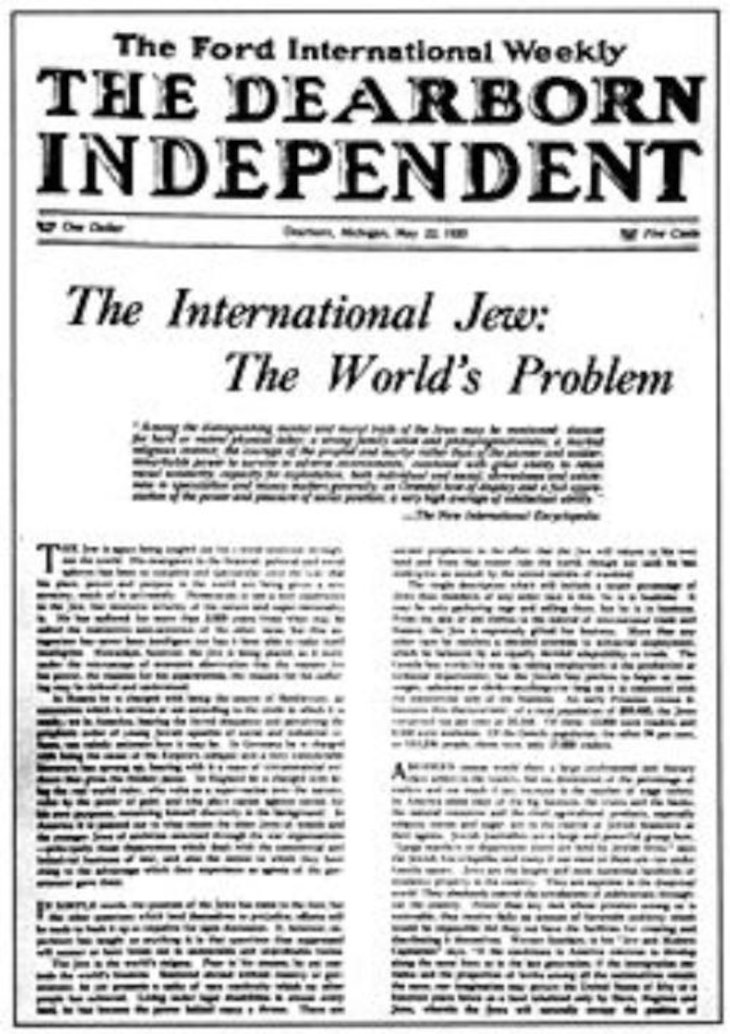

The article that signaled tbe beginning of Henry Ford's seven-year hate campaign against the Jews. (COLLECTIONS OF THE HENRY FOR MUSEUM, GREENFIELD VILLAGE)

The article that signaled tbe beginning of Henry Ford's seven-year hate campaign against the Jews. (COLLECTIONS OF THE HENRY FOR MUSEUM, GREENFIELD VILLAGE)

As frightening as that sounds, Henry Ford did much the same thing in his day. Ford used his money and influence to finance The Dearborn Independent, a nationally distributed newspaper, dedicated in large part to the propagation of his antisemitic worldview, in which he first published excerpts from The International Jew. With a circulation that reached 900,000 by 1925, it was second only to The New York Daily News in scope. The tragic effect of Ford’s widespread hate mongering on Jews, both in America and worldwide, was so devastating it’s impossible to overstate.

The International Jew is rife with outlandish proclamations: *

Jazz is a Jewish creation. The mush, slush, the sly suggestion, the abandoned sensuousness of sliding notes, are of Jewish origin.

Jewish songwriters are deliberately poisoning the minds of pure Christian youth with the decadence of their music.

But alongside those proclamations, and the malevolent ignorance of the book’s overall conceit, in which a mysterious cabal of super-Jews are using their devilish ingenuity and international reach to destroy the world—there was one idea that Ford kept coming back to:

There is lacking in the Gentile a certain quality of working-togetherness of intense raciality, which characterizes the Jew. It is nothing to a Gentile that another man is a Gentile; it is next to everything to a Jew that the man at his door is another Jew.

It was as if that very notion had pained Ford, not just in some general or academic sense, but personally. He couldn’t seem to wrap his head around why Jews—Jews who’d never met one another, Jews who didn’t share a common language or a cultural heritage — could be so immediately at home with one another. How was it, he wondered, that the Jews, a people that had been in exile for thousands of years and virtually cut off from each other, could create such an immediate sense of trust and familiarity?

Ford couldn’t fathom the innate concern a Jew has for a fellow Jew.

What Ford could never fathom is what Jews call Ahavat Yisrael, the innate concern a Jew has for a fellow Jew. This, of course, is not to say that a Jew doesn’t have, or is not capable of having, God forbid, concern for others! In the same way that I’m more concerned about my brother than my closest friend, and my closest friend more than a mere acquaintance; this hierarchy of concern is instructive as to how to care about all people.

Ford was correct in one sense. When I, a Minneapolis-born Jew meets a Jew from Tehran, for example — someone I’ve never seen before, someone whose language and cultural outlook is entirely different from mine —I know we still say the same prayers, still observe the same laws of kashrut, still shake the same lulav, and still eat the same matzah; those 3,300-year-old traditions can create an instant, and sometimes indelible bond. Despite the differences, whether political, religious, or cultural there often remains a thread of familial-level connectivity.

But what is it specifically, that binds one Jew to another. What is at the root of the “international” closeness that so worried Ford? Is it a cultural or culinary connection like a love for the stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer or gefilte fish? Or is it a shared language—Yiddish or Ladino, for example?

Those things are not unimportant, but they but are tangential. Nor do I think that Jewish unity comes about as a result of ‘the oppression we’ve faced over the millennia’ —an answer to that same question which too often is promulgated by Jewish leaders who wonder why there is so much apathy towards Judaism among the young, and who would urge people to donate to a Holocaust museum more readily than they would a Jewish day school.

What I’ve come to understand is that the Torah itself is at the root of the deep, almost mystical dimensions of Jewish unity.

What I’ve come to understand is that the Torah itself is at the root of the deep, almost mystical dimensions of Jewish unity. Clearly, many don’t accept the Torah’s Divine origins, many dispute the present-day relevance of certain of its laws, still many others may consign the entire Torah to mere historical artifact. But one thing is indisputable: Unlike any other people on the planet, the Jewish nation has remained intact throughout its 2,700 years of diasporic existence. And I believe that was possible because the Jewish people are the beneficiaries —and mission-driven guardians —of the Torah’s proactive testimony of laws, remembrances, and highly specified codes of morality. In his book, A History of The Jews, historian Paul Johnson writes of the proactive, mission-driven nature of the Jewish people:

Certainly, the world without the Jews would have been a radically different place. Humanity might have eventually stumbled upon all the Jewish insights. But we cannot be sure. All the great conceptual discoveries of the human intellect seem obvious and inescapable once they had been revealed, but it requires a special genius to formulate them for the first time. The Jews had this gift. To them we owe the idea of equality before the law, both divine and human; of the sanctity of life and the dignity of human person; of the individual conscience and so a personal redemption; of collective conscience and so of social responsibility; of peace as an abstract ideal and love as the foundation of justice, and many other items which constitute the basic moral furniture of the human mind. Without Jews it might have been a much emptier place.

The Jewish people’s obeisance to the Torah has been the cause of untold enmity against them. But much more importantly, it has been, and will continue to be, the wellspring of enduring pride, hope, and unity.

*In April 1924, the Independent initiated a new series of attacks on attorney Aaron Sapiro, accusing him of exploiting farmers’ cooperatives. When Ford refused to print a retraction, Sapiro sued him for libel. The case finally came to trial in March 1927 and quickly turned into a media circus. Shortly before Ford was scheduled to testify, he ordered the closing of the Dearborn Independent (it closed at the end of 1927) and explored an out-of-court settlement with Sapiro. After negotiations with U.S. Representative Nathan D. Perlman, a vice president of the American Jewish Congress, and Louis Marshall, president of the American Jewish Committee, Ford agreed to release a formal apology, written by Marshall, and to make a cash settlement with Sapiro.

Strangely, there were Jews employed by Henry Ford in the Ford Motor Company, even in executive positions. Read, "Coming Out of the Ice" by Victor Herman. Herman, a Detroit Jew born 1911, relates early in this autobiography, his father's employment and relationship with the great industrialist. Ford's anti-Semitism seemed to be rooted more in a strange preoccupation coming from ignorance than any personal antipathy to Jews. But the reaction from the readers of The Dearborn Independent was no different than from readers of any other anti-Jewish tract. When it came to Henry Ford, the only saving grace was, his progeny weren't Jew haters. I have owned Ford vehicles, as well as some Jewish friends and never heard a word alleging the company is a threat to Jews or Israel.