Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

7 min read

Swastikas have a long history and are widely employed around the world today.

The state of Victoria in Australia has made it illegal to display swastikas. After racist incidents increased 750% over the past year and a half, Victorian legislators moved to ban the Nazi-linked image.

“Victoria has now become the first (state) in Australia to ban the public display of the Nazi symbol, recognizing its role in inciting antisemitism and hate,” tweeted Jacyln Symes, Victoria’s Attorney-General and Minister for Emergency Services.

Brazil, Germany and Hungary also ban public displays of swastikas.

Although the swastika is identified with Nazism today, the symbol has a long history and continues to be widely used in art, architecture and religious devotion today.

Here are 6 facts about this powerful symbol.

The word swastika comes from the Asian language Sanskrit, where svastika means good luck and success. The earliest images of swastikas in Asia date back thousands of years.

Pictures of swastikas were a common design on ancient Mesopotamian coins and were carved into temples and homes. These ancient swastikas appeared in two forms: the more familiar version that is associated with Nazi Germany which appears to be rotating clockwise, and a counter-clockwise version (called a sauvastika in Sanskrit).

While the svastika was associated with the movement of the sun across the sky and had positive connotations, the sauvastika was commonly associated with nighttime, fear and death.

Swastika images have been found in cultures around the world, including in Europe and in native American art. (Swastikas – and sauvastikas - are particularly common in Navajo art.) The meanings of these designs varied. In many cases swastikas were associated with various gods and goddesses in diverse cultures. In India, swastikas are associated with the god Ganesh, bringer of luck, while the backwards sauvastika is used as a symbol of Kali, the Hindu goddess of death.

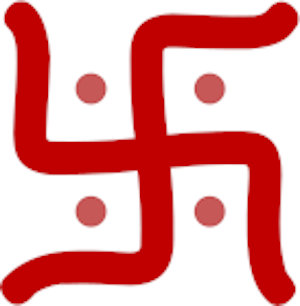

Hindu swastika

Hindu swastika

In northern Europe, this image was associated with the Norse god Thor, who was said to control storms and thunder and was one of the most powerful idols in the Norse pantheon. In Buddhism, swastikas represent the intellect of the Buddha. They are often imprinted into statues of Buddha on the heart, feet or hands and are sometimes used to decorate Buddhist temples and ritual clothing.

For adherents of the Jain religion, swastikas represent their seventh saint, and are also used to represent the concept of rebirth. In May 2022, archeologists excavating near the Gyanvapi Mosque in the southern Indian city of Varanasi found two old swastikas carved near the old mosque, raising the possibility that this symbol was sacred to Muslims in the area.

Even Christianity has used the swastika symbol. Early and Byzantine Christian art contain swastikas. Some versions of the crux gemmate, the “jeweled cross” that was popular in the Middle Ages, were represented in swastika form.

Swastikas – and sauvastikas – continue to be popular motifs in much of the world today. In Indonesia and India, swastikas are carved into houses and temples as a sign of prosperity.

Home décor being sold on Ali Express

Home décor being sold on Ali Express

Swastika is also a girl’s name in India, where it means lucky.

In the 1800s, the great German archeologist Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) did much to popularize archeology – and also the swastika image. While excavating the site of ancient Troy in Turkey, Schliemann unearthed images of ancient swastikas. He’d seen similar designs on old pottery back in Germany and was excited by this coincidence.

Schliemann formulated the theory that a common Euro-Asian civilization had used swastikas in their religious worship, and that the image had spread widely across Asia and Europe in ancient times. This theory fit neatly into the burgeoning (and today largely discredited) idea that a common Aryan ancestral civilization settled in present-day Iran then spread into Europe and India, bringing with them their religious symbols and language (as well as their supposedly superior genetic makeup).

Swastikas became popular in the 1800s in Germany and elsewhere Europe, and for a time they were seen as a symbol of Europe’s ancient past. But the overtly racist tones of German interest in their “Aryan” ancestors transformed the swastika into a nationalist symbol. Known as the Hakenkreuz, or hooked cross, in German, swastikas eventually became associated in Germany with the far right and with anti-Jewish feeling. After World War I and the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the swastika was the symbol of groups who wanted to create a racially “pure” German state.

As he wrote his anti-Jewish screed Mien Kampf in 1925, Adolf Hitler described creating a new German flag: a black swastika on a white disk, placed against a red background. The colors of his proposed flag echoed the old imperial German flag, and the swastika represented a racially pure “Aryan” Germany. After gaining power in 1933, Hitler mandated that the Nazi flag he’d designed be flown on all government buildings.

A protest in New York two years later was the ostensible impetus for Hitler to mandate that his swastika-featuring flag become Germany’s national icon. One day in July 1935, several hundred Americans swarmed the German passenger ship SS Bremen as it lay docked in New York’s harbor. They were outraged at recent anti-Jewish actions in Germany and wanted to protest. They took the swastika-emblazoned flag from the ship’s mast and ripped it up, throwing it into the Hudson River.

Hitler’s government protested the move and vowed revenge. Soon after, while passing the infamous Nuremberg Race Laws disenfranchised Germany’s Jews and enshrined anti-Jewish discrimination in German law, Hitler ordered the passing of a Flag Law. The Nazi flag, with its large swastika, was now the official flag of Germany.

Following the Holocaust, many European nations – including Germany and other countries allied with Germany during World War II such as France, Italy, Hungary and Austria - banned the display of swastikas. While displaying a swastika is illegal in much of Europe today, in some other regions of the world swastikas are an ever-present symbol signifying rising hatred of Jews.

The Anti-Defamation League notes that: “Among white supremacists, the swastika is a very common symbol… Since the (1998) release of ‘American History X,’ a favorite movie of white supremacists, it has been very common for male while supremacists to get a swastika tattoo on their left breast in imitation of the mains character in that movie. One trend seen most often in California among members of white power gangs is the popularity of very large outline swastika tattoos.”

USA Today has noted that the popularity of swastikas has been rising for a while: “It is more popular than ever among non-ideological haters – kids, vandals, anyone out to shock or rebel or express a personal grudge against someone who happens to be Jewish, black, Hispanic or gay.”

Part of this trend, the newspaper notes, is that organized hate groups have begun to try and discourage the use of swastikas, on the assumption that such an offensive symbol detracts from their image and might scare off potential supporters.

That seems to have been the case recently in Gaza. There, in 2019, Hamas, the terror group which calls for the destruction of the Jewish state, asked its supporters to stop waving Nazi swastika flags at protests because it made them look too extremist and might deter international supporters from backing the terror group.

With the recent uptick in anti-Jewish hate around the world, it’s possible that we’ll be seeing more swastikas displayed – not as ancient Asian religious symbols, but as anti-Jewish motifs.

There are 2.5 billion people, the Dharmic people: Hindus, Buddists, Sikhs and Jains, who regard the Swastika as sacred.

The Swastika must not be sullied because of its misuse by Herr Shicklgruber.

There is no total ban on the swastika in either Germany or Australia as there are legal exemptions for its full use by the Dharmics.

Israel cannot afford to alienate the Hindu and Buddhists Worlds by opposing the Swastika.