An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

6 min read

Changes made to federal law ensure that the Justice Department can step in when houses of worship are threatened.

Mazel tov to author Faygie Holt for winning a first place Simon Rockower Award for excellence in North American Jewish History for this article.

That the FBI is helping local law enforcement investigate the deadly racially-motivated shooting at the TOPS supermarket in Buffalo, N.Y., comes as a surprise to no one. Most take it for granted that the nation’s leading criminal investigators will help in cases of racial and antisemitic terror.

But this wasn’t always the case.

For years, the FBI declined to help investigate bombings and threats against Jews, African-Americans and other minorities because such attacks didn’t violate any federal laws.

It was the Civil Rights Act of 1960 that made the sending of threats to a religious institution or to “travel interstate” to avoid prosecution for damaging by fire or explosive any house of worship a federal offense.

In fact, one of the first times the FBI officially helped local police with an antisemitic investigation into a bomb threat was in Buffalo, N.Y. It was in April 1960 when Temple Beth Zion was desecrated with swastikas and the synagogue’s rabbi, Martin Goldberg, received a letter with a bomb threat.

It was a spate of bombings in the south in the late 1950s that helped usher in this change in the federal law.

White supremacist were spewing hateful rhetoric and terror followed, as a spate of bombings targeted synagogues and African-American churches and schools.

The year was 1957 and the right to equality for African-Americans was being waged across the south. Members of white supremacist groups like the KKK were actively spewing their hateful rhetoric and terror followed as a spate of bombings targeted synagogues and African-American churches and schools.

In Charlotte, N.C., a group of 30 women were inside Temple Beth-El when someone left a bundle of dynamite outside the synagogue. The fuse had been lit, but it burned out before it reached the explosives. The community was physically unharmed, but scared.

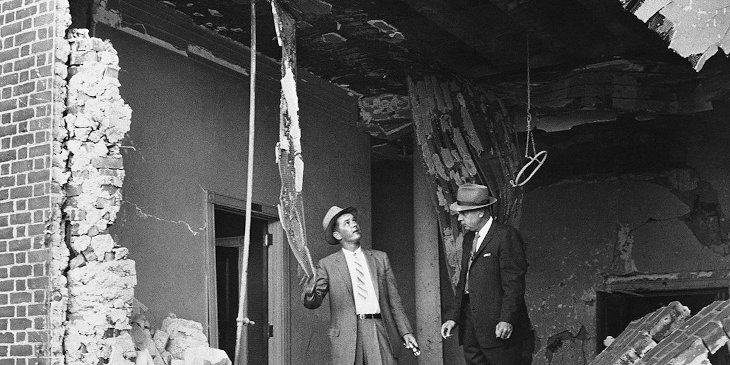

Atlanta’s “The Temple” was bombed in 1957.

Atlanta’s “The Temple” was bombed in 1957.

Several months later, a bomb was discovered outside a synagogue in Gastonia, N.C., before it could go off. That was followed by an attempted bombing of a synagogue in Birmingham, Ala., where more than 50 sticks of dynamite were found.

Things took a much more ominous turn when a bomb exploded at Temple Beth-El in Miami. Unlike the previous incidents, this one, on March 16, 1958, caused significant damage to an Orthodox synagogue. That same day a bomb went off at the Jewish Community Center in Nashville, Tenn., also causing damage. A rabbi in Nashville had received a call from someone with a group calling itself the “Confederate Underground” threatening more violence.

“Bombing of Synagogue Part of National Plot?” screamed a headline in the Miami Herald.

The attacks in Miami and Nashville were followed by the bombing of the Jewish Community Center in Jacksonville, Fla., in late April. A man claiming to be a part of the “Confederate Union” called in a threat.

Thousands of dollars were set aside as reward money to catch the perpetrators, but no one was arrested. Jewish groups and local law enforcement appealed to the FBI to get involved.

As the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported at the time, “The American Jewish Committee in a wire to the Attorney General [William P. Rogers] stressed that the ‘series of bombings’ clearly indicated a concerted course of criminal action on an interstate scale and ‘points to the existence of a conspiracy which warrants an immediate investigation by the FBI.’ ”

Despite the devastating attacks to the Jewish community, no federal laws had been broken.

Despite the devastating attacks to the Jewish community, no federal laws had been broken. As then New York Sen. Jacob Javits testified on the floor of the Senate in April 1958: “It is my understanding that the Department of Justice, through the FBI, is investigating certain of the bombings with threats, but the jurisdiction under which the Justice Department operates in unnecessarily narrow, and calls for immediate amendment of the existing criminal law.”

On Sunday, Oct. 12, 1958, an explosion shattered the predawn silence in Atlanta. The “Confederate Underground” called the offices of a national news bureau taking credit for bombing a temple.

But it wasn’t until 7:45 AM when a janitor arrived at The Temple, as the synagogue is called, that the destruction was discovered. More than $100,000 worth of damage was reported with stained glass windows shattered, the hallway demolished, and piles of bricks and plaster scattered around.

President Dwight Eisenhower was in New York that morning speaking at a cornerstone-laying for a church and said, “I think we would all share in the feeling of horror that any person would want to desecrate the holy place of any religion, be it a chapel, a cathedral, a mosque, a church or a synagogue.”

Yet the attacks continued. A few days later, a synagogue in Peoria, Ill., was bombed. The terror that had been confined to Jews in the south was moving north.

Unlike the other bombings, Atlanta police were able to identify a suspect. George Michael Bright, who was known to have antisemitic leanings, and four friends were arrested. Police had evidence but no concrete smoking gun. Despite the prosecution’s best efforts, the jury was unable to agree on a verdict. A second trial ended with Bright’s acquittal. He was free to go and charges against the others were dropped.

No one, it seemed, would be held responsible for the terror that was being inflicted on Jews. The cry for justice was loud.

Attention turned to what Senator Javits had earlier called the “narrow” jurisdiction for federal investigators to aid local law enforcement. With the support of the president, federal law was enacted which made it a crime to travel “interstate” to avoid prosecution or confinement in connection with the destruction or attempted destruction of a house of worship, religious center or educational institution.

It also made it a federal offense to use the “mail, telephone, telegraph or other instrument of commerce” to convey a threat against a building or personal property to interfere with a religious, charitable, educational or other institution.

Those statutes, aimed at giving federal authorities the right to intervene in cases of domestic terrorism against houses of worship and religious institutions, was codified into law as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1960.

In this time of record-breaking antisemitic incidents and increasing hate crimes in the United States, and where threats continue to be lobbed against houses of worship, the legacy of these attacks and the changes to the federal law they ultimately spawned live on.