Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

6 min read

Nature's greatest mysteries are surprisingly personal.

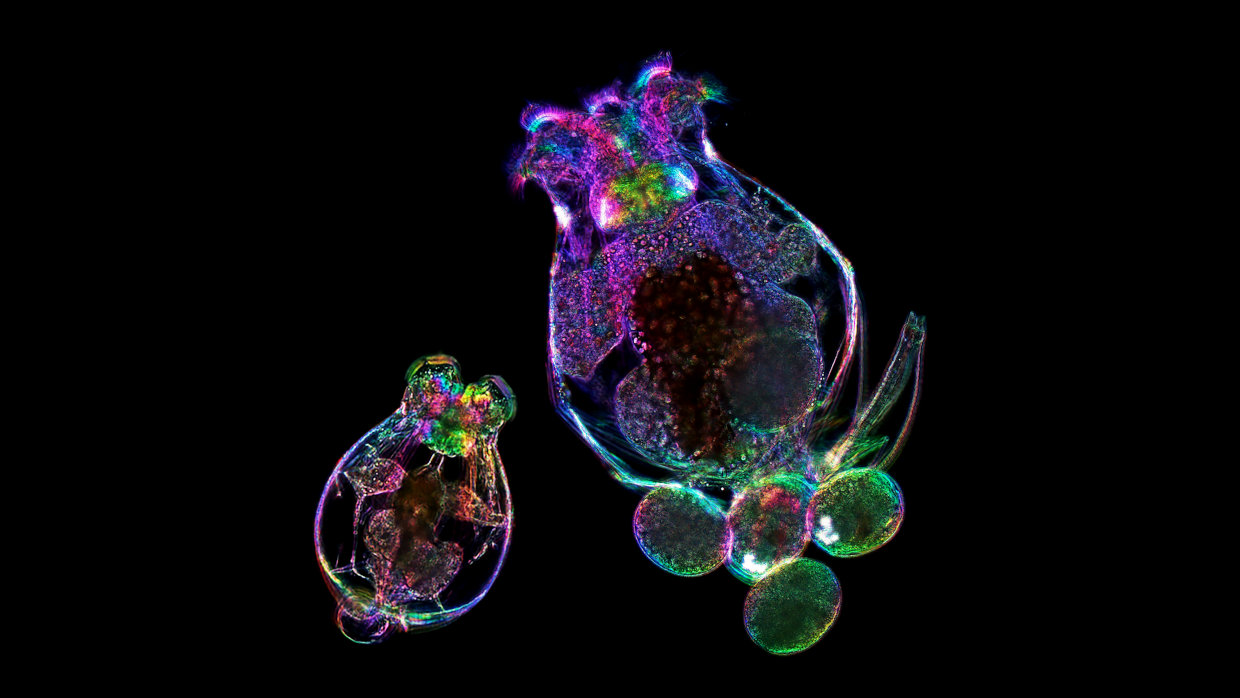

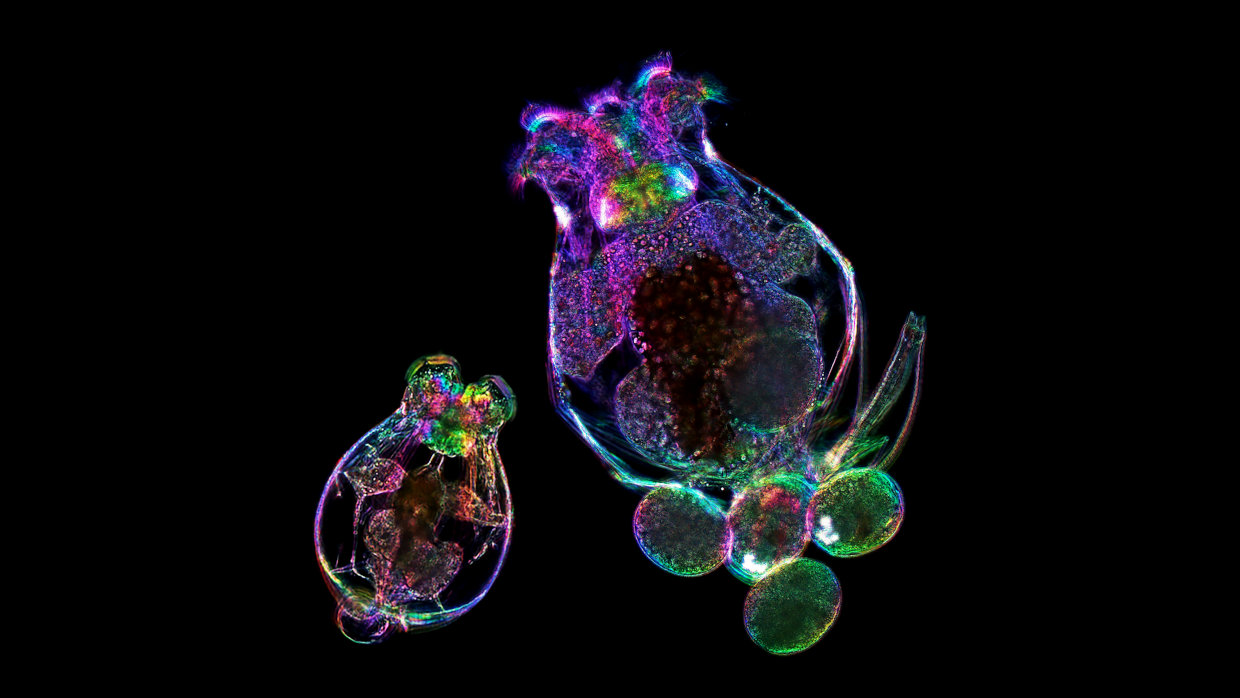

Their heads spun like tiny, electric toothbrushes. Suddenly in focus under the microscope’s lens in our sixth-grade science class, these strange creatures swam freely through the drop of greenish pond water I’d collected from a bucket in my backyard. There must be a whole universe in there, I thought to myself.

I was already curious about the microscopic world, and I had some ideas about what I could expect to find. But these small beings were entirely new to me. Some of them swam through the water like fish, while others anchored themselves to pieces of debris and swayed with the microscopic currents. One would occasionally contract its long, worm-like body into a small sphere. Strangest of all, their Y-shaped heads were lined with tiny bristles that seemed to rotate freely.

I had discovered an alien.

I learned later that these microscopic animals are called rotifers, and they’re quite common. But that did nothing to dampen my enthusiasm. On the contrary, every drop of water and speck of dust was now brimming with alien life, awaiting my exploration. Encountering a world filled with wonder, I became a bit of a wonder junkie.

Every drop of water and speck of dust was now brimming with alien life, awaiting my exploration.

Ant colonies, the periodic table, our solar system – each subject filled me with awe and a sense that deeper mysteries await. I was overwhelmed with a desire to simply know. Every new fact seemed to extend me; everything was surprising and required me to adjust some assumption about the world.

I remember a phase when I was obsessed with parasites (my poor parents listened patiently to my lectures on the tapeworm’s lifecycle, which I sadistically reserved for mealtime). These creatures made me wonder about what it actually means to be alive and how all life is deeply interdependent.

I don’t know what exactly drove this "wonderlust," but I remember when it started to change. As school work became more demanding, I didn’t have time to poke and prod my way down the library's long bookshelves, searching for a new subject to explore. And I was tired of simply knowing things. I wanted to understand things now. Most of all, I wanted to understand myself.

Ian Schneider, Unsplash.com

Ian Schneider, Unsplash.com

Poetry and literature became interesting to me. This was a new type of wonder, a new way of exploring. It had different rules, too. A microscope does a great job of revealing the secrets within a murky drop of pond water, but what tool do you use for your own inner world? What lens can magnify and focus everything that's swimming around in there? For millennia, humans have used art to plumb their own depths and drag up those hidden parts of themselves.

But in turning so far inward, I wondered if I was being self-indulgent. Was I learning more about myself at the expense of true discovery – the kind that happens out there, in this awe-inspiring universe, filled with beautiful rotifers and mysterious tapeworms?

In his new book, Awe, Dr. Dacher Keltner describes a study that surveyed thousands of individuals from around the world to see which types of experiences brought them a sense of awe. Ultimately, the answers fell into eight major categories, which Keltner calls the “Eight Wonders of Life.”

What do you think was the most common category? The wonders of the natural world, perhaps?

Nope.

The emotional charge of a beautiful song?

Nope again.

The exquisite design of an architectural marvel?

Most decidedly nope.

Actually, it was the breathtaking special effects of James Cameron’s new Avatar movie.

Alright, it wasn’t.

Across culture, language, and continent, our most common experience of awe is found in instances of moral beauty – moments in which we witness extraordinary courage, kindness, overcoming, or other human virtues. Keltner explains that it is moral beauty that is most likely to make us feel that we are “in the presence of something vast and mysterious that transcends our current understanding of the world.”

That was surprising to me. I could understand moral beauty being the most admirable or noble of experiences, but is it awe-inspiring? Is an act of kindness truly more “vast and mysterious” than the discovery of microscopic aliens in our pond water? Can courage hold a candle to the kaleidoscopic landscapes of shimmering galaxies that our largest telescopes reveal?

But as I asked myself these questions, I noticed a part of myself that wasn’t surprised at all by Keltner’s conclusion. It was the same part that had begged me to turn inward and go beyond the facts to ask myself what the facts mean to me.

Michel de Montaigne, the 16th century writer and philosopher, became famous for his insightful explorations of his own personal experiences. He tackled weighty subjects, like cruelty and death, but he devoted equal attention to the common and the mundane, like his experience of playing with his cat. At the heart of his project was the idea that “this great world… is the mirror in which we must look at ourselves to recognize ourselves from the proper angle.” To truly understand ourselves, we have to look outward.

”This great world… is the mirror in which we must look at ourselves to recognize ourselves from the proper angle.”

The 19th century rabbi, Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, writes that this is the deeper meaning behind Adam’s naming of the animals in the story of Creation. Adam wasn’t yet acquainted with his own inner world. Emotions like anger or compassion were entirely foreign to him – after all, he’d never had a reason to experience them. When he began selecting names based on the animals’ unique qualities, he realized that he wasn’t simply observing these qualities – he was understanding them. He was sensing the moral beauty within the natural world, from the gentleness of the mother bird to the industriousness of the worker bee, and this showed him that these qualities must also be latent within him.

The world will always be a place of wonder for us, and we will always find enough complexity there to drive our quest for new knowledge. But it seems to be moral beauty, not complexity, that will bring us to the heights of awe, and maybe that’s because there is nothing as mysterious to us as ourselves.

The natural world gives us a way to approach that mystery when we view it through the lens of moral beauty. Just like the microscope makes the invisible suddenly visible, this new lens makes the foreign suddenly personal. What was before so different, so other, can become strangely and powerfully relatable – whether we find that relatability in the tapeworm's selfish clinging to abundance or in the rotifer's calm filtration of whatever the current brings.

For me, it was wondrous to peer into a drop of water and discover something alien there. But it’s much more wondrous – and transformative – to peer into that same drop and meet something so utterly and mysteriously familiar.