Columbia Students Once Rallied Against Nazis — Now They Cheer for Them

Columbia Students Once Rallied Against Nazis — Now They Cheer for Them

8 min read

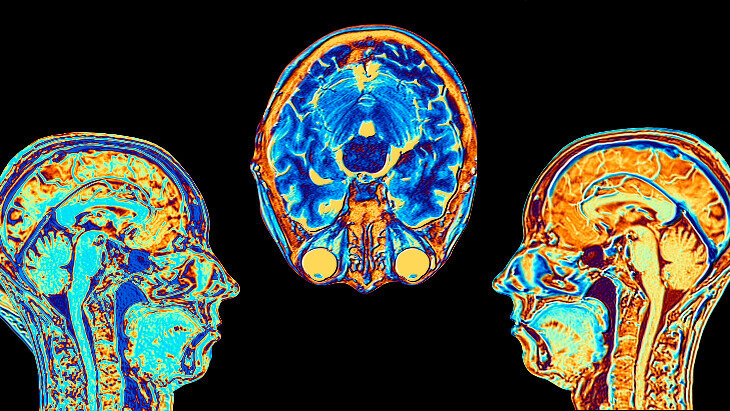

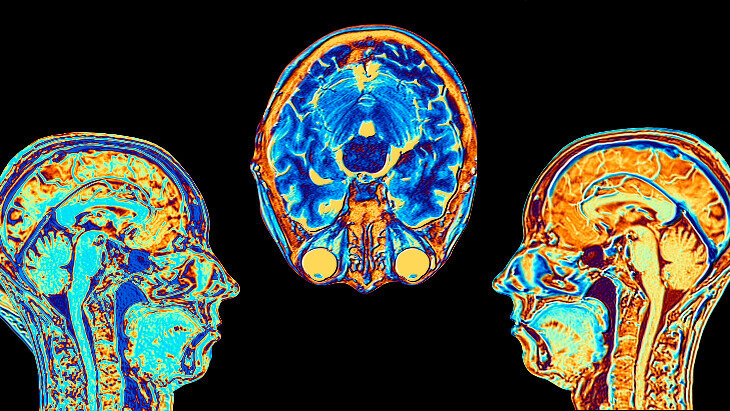

Does our consciousness reside in our bodies, beyond them, or both?

What can the philosophy of mind tell us about our place in nature?

Humanity's position in the order of Being might sound like too big or too mystical a destination to reach through what is often quite a dry branch of philosophy. At the very least, you might think it odd that the investigation of what lies between our ears has anything to say about Being, or nature, as a whole.

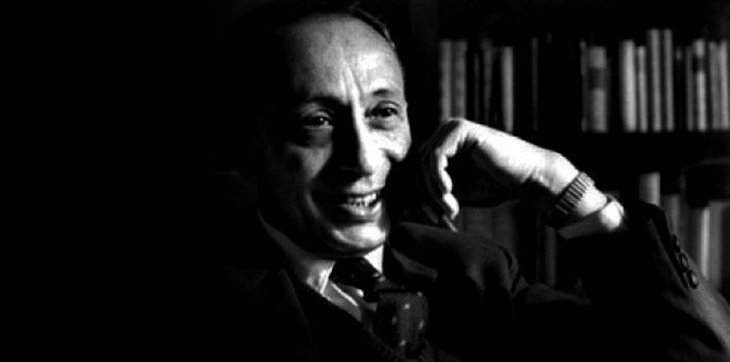

But I think it does. And one philosopher who shows us this is the German-Jewish thinker Hans Jonas (1903-1993).

Most philosophers of mind approach the topic in two ways, and Jonas is no different.

The first step is to look 'inward' and study the contents and structures of subjectivity: the will, for example, or the imagination. What do these actually involve? The second step is to look 'outward' at where the mind is located in the world. Is it anchored in the brain?

Many – perhaps most – contemporary philosophers would answer 'yes' to the latter question. Some of those philosophers would go on to argue that only human beings, who possess very large brains relative to the size of our bodies, are conscious. A greater proportion would probably go further than this and argue that plenty of non-human animals are conscious as well.

Not many philosophers, however, would say no; the mind isn't simply located in the brain – it's located in the whole body of a living organism and present in all lifeforms: human, animal, and even plant.

The reason this is a rare view might be, admittedly, because it sounds a bit mad at first. If we can be sure of anything at all, then we can be certain that goldfish don't compose poetry in their heads, nor dandelions make plans for the weekend. But there are convincing versions of the idea that consciousness is spread, albeit unevenly, throughout the living world – and Jonas' philosophy is one of them.

Jonas' starting point is to insist on the unity of the mind and the body as a whole, not just the mind and the brain. As far as he's concerned, you don't 'have' a body – you are your body.

Jonas' starting point is to insist on the unity of the mind and the body as a whole, not just the mind and the brain. As far as he's concerned, you don't 'have' a body – you are your body.

This idea not only runs against a long history of thinking of ourselves as souls who inhabit bodies but also sci-fi stories like The Matrix and Avatar, which suggest that the mind could be uploaded to a computer or different organism. Jonas instead believes in the unity of the mind and body. He does so because when we turn inwards and examine our inner mental life, we find that whether we're thinking, feeling, remembering, imagining, or desiring, our body is always there, giving structure to those acts of subjectivity.

Say, for example, that I'm thinking about a conversation I had with a friend which turned argumentative. I might mull over the words he said, the words I said, and think about exactly when the tension had emerged and why. But words alone would only tell half of the story. I would also have to think back to our gestures, the intonation in our voices, the posture of our bodies, and the physical space between us to gather together the full meaning of our conversation.

In other words, the communication of thoughts and feelings is inherently embodied. And it's not only the conversation itself that takes this form – even my recollection of it is bodily in that I would feel a tightness in my chest and my blood pressure rising as I relived the argument.

Jonas claims that our every thought and deed is made possible by the body and structured by it to a greater or lesser extent. And in his hands, this insight acts as a key to unlocking a new perspective on the world and our place in it.

Hans Jonas (Source: Kritische Gesamtausgabe der Werke von Hans Jonas)

Hans Jonas (Source: Kritische Gesamtausgabe der Werke von Hans Jonas)

So far, Jonas' ideas are only moderately countercultural. Where he goes next in his quest to reconnect us to the living world is full-on philosophical Woodstock.

Because our embodied minds (or conscious bodies, if you prefer) give us a clue as to the nature of reality, the immediate evidence each of us has of our bodily consciousness tells us that matter can have inwardness, interiority.

We know, in other words, that at least part of the objective world is also inseparably subjective. And, of course, since the living human body is a product of nature, as the theory of evolution shows, this means that the mind, too, is an outgrowth of the natural world.

Because our embodied minds give us a clue as to the nature of reality, the immediate evidence each of us has of our bodily consciousness tells us that matter can have inwardness, interiority.

Here we're faced with something of a conundrum. However, as it could be that the mind, though grounded in the whole of the living body, is just a late evolutionary adaptation of human beings – like opposable thumbs, for example, or the fact that we have to rear our children through an extremely long and gruelling period of adolescence. (Other animals' offspring fly the nest earlier, and everyone involved is probably happier for it.)

But Jonas argues that the opposite is true: that the mind is present in non-human life and that evidence of it can be found even in the most basic single-celled organism.

It's a bold claim, almost heretical. But just as the conversation between myself and my friend showed embodied minds at work, so too do the actions of plants and animals. As such, Jonas argues that we can survey the natural world for subjectivity as witnessed in the behavior of living things.

While animals are incapable of speech and abstract thought, a more fundamental consciousness is identifiable in their capacity for emotion and locomotion. Think, for example, of a cat stalking its prey, demonstrating evidence of intention and anticipation. We could also recall the way a humble woodlouse will curl into a ball as the first sign of a threat, a response that suggests self-preservation. And even the limited behavior of plants betrays a trace of subjectivity. In a flower, there is nothing as complex as emotion and locomotion but rather a gradual movement toward light, water, and minerals in order to survive. Plants can't think or feel but can sense aspects of their environment.

All lifeforms, no matter how complex or primitive, have a share of freedom and world-openness because this is what is required to live, to continue in being

What do all of these examples have in common? Jonas' answer is that they represent degrees of 'openness' to the world and the freedom to act within it. All lifeforms, no matter how complex or primitive, have a share of freedom and world-openness because this is what is required to live, to continue in being. Jonas' philosophy of mind thereby arrives at a theory of Being in which life takes pride of place, and humans represent its pinnacle.

Some readers will think this is just anthropomorphic: that Jonas mistakenly projects the human mind onto animals, plants, and fungi, possibly as a result of consuming too many of the latter.

However, other readers, such as myself, find inspiration in his philosophy – and even some solace. Because if Jonas is correct, and humanity's place in nature is atop a scale of living beings characterized by freedom and world-openness, then we are not separate from the remainder of life and merely living in nature. Rather, we belong to it.

In this way, we can feel a little more at home in the world – and that is no bad place for a philosophy of mind to end up.

[Editor’s note]: It’s exciting to see philosophers and cognitive scientists expanding the boundaries of consciousness. My only hope is that they will take it even further. In classical Jewish thinking, there is a Universal Consciousness that pervades the entire material world and beyond, as Isaiah wrote “the whole world is filled with His glory.”

Yes, plants, animals, and even our individual cells exhibit a type of awareness. Some even see a kind of consciousness at work in an inanimate matter when observing phenomena like the water and rock cycles.

We would say though, that Jonas’s idea that “you are your body” is incomplete. It would not solve the mind/body problem as we would just be forced to ask “if we can’t explain how a brain is capable of generating consciousness, how would we expect the rest of the body to pull it off?” In the Jewish way of thinking, our essence/consciousness/soul and body are more linked than people realize but the soul is not imprisoned in the brain, body, or any material entity.