Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

6 min read

Free will issues. It's complicated.

The answer to this question is "yes," but not in the way you might think.

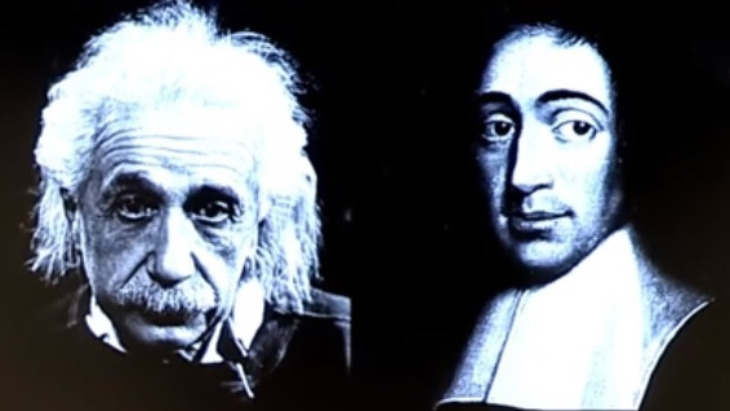

The seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza held some controversial views—including the impersonal nature of God—that caused him to be expelled from the Jewish community in Amsterdam. One of these controversial views is his denial of free will, though he doesn't mean this in the usual sense, for which every movement of every particle in the universe is predetermined. But what he does mean continues to be the subject of debate among philosophers.

Spinoza defines the will as "affections," the bodily emotions that permeate our experience and motivate our actions. He asserts that these feelings are determined, and some philosophers interpret this to mean that we have no freedom of choice and that all of our actions are controlled by our emotions. In this interpretation, all we can do is try to be happy with our fate.

But then a question arises: how can we try to be happy with our fate if all of our emotions are entirely determined, including our happiness or lack thereof? This is a paradox, which leads to a deeper interpretation partially derived from the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, which is based in part on the work of Friedrich Nietzsche.

To understand this more subtle interpretation, we have to take a brief detour into the four kinds of causation posited by Aristotle in antiquity, two of which are particularly relevant in this case. The first kind of causation is the efficient cause, which is what we generally think of when we talk about cause and effect: things (usually material things) acting on other things, like a billiard ball striking another billiard ball. The second kind of causation is the formal cause: the conception that all things are the expressions of Forms or Ideas, universal essences that exist somewhere in reality (though exactly where and how is a subject of much debate).

This mode of causation can be a bit harder for modern minds to envisage. Still, it was perhaps the primary causal mode in antiquity (along with final causation), when everything was understood as ruled by one god or another, as expressing their specific power (love, anger, etc.)

The philosophers who interpret Spinoza as a mechanistic determinist read him as claiming that we have no freedom of choice, that we merely act out our fate like machines. However, what these philosophers seem to have missed is that, for Spinoza, the primary mode of causation that determines the will is formal causation, perhaps even more than efficient causation, though these are two parallel explanations for the same processes. For a determinism based on efficient causation, the movement of every particle would be determined by the universe's initial conditions. On this view, we and everything else would simply be playing out the moves dictated by our fate, even me writing this article and you reading it.

In Spinoza's conception…the emotions that we constantly negotiate like surfers riding an endless series of waves, are themselves the will, the desires and impulses that cause us to act.

A determinism based on formal causation is very different. In Spinoza's conception, the affections, the emotions that we constantly negotiate like surfers riding an endless series of waves, are themselves the will, the desires and impulses that cause us to act. And these emotions which constitute the will are the expressions of formal causes more than efficient ones.

But the interesting thing about formal causes is that, unlike the actions of billiard balls, emotions can be expressed in many different ways. Anger, for instance, can lead to destructive violence, but it can also impel the person to channel their rage creatively, to write a song or work for social justice.

For Spinoza, the formal causes manifest as emotions that determine our will. Still, we have the "freedom of mind" to choose how to express those emotions, whether in an Oedipal rebellion against a father figure or in the composition of Anti-Oedipus, the important work by Deleuze and Guattari that critiques the dominance of the Freudian Oedipal complex.

On this view, we can't control how we feel, but we can control what we do about our emotions. And as Spinoza suggests, expressing our emotions in a more creative, active way can cultivate more positive emotions, while expressing feelings in a destructive, reactive way tends to produce more negative ones. So, in another paradox, our emotions are determined, but the way in which we choose to express those emotions can help determine which emotions we will feel in the future.

So, in another paradox, our emotions are determined, but the way in which we choose to express those emotions can help determine which emotions we will feel in the future.

Although the issue of "free will" is usually framed as a binary decision between a complete determinism and a complete freedom of choice within the constraints of physical reality, this subtler view, though still controversial even among Spinoza scholars, serves to integrate determinism and freedom by dissolving the opposition in a deeper perspective.

Ancient Stoic philosophers perhaps presaged this perspective in the concept of amor fati, the "love of fate," though it took a few thousand years for the finer details of this conception to be worked out by Spinoza, Nietzsche, Deleuze, and others. For these philosophers, the love of fate is not merely reconciling oneself to playing out a life in which every moment is determined in advance down to its smallest detail. Rather, amor fati is the recognition that our emotions determine our will, that our emotions constitute our destiny, but that we have the freedom to choose how to express these emotions.

Thus, we can choose whether to fulfill our destiny or not, and to express that destiny at a lower or higher register, as the son who unconsciously acts out an Oedipal rebellion against the father or as the philosopher who writes the epoch-defining work against the exclusive dominance of the Oedipal complex. Every emotion demands to be expressed one way or another, but choosing how to express these emotions is the primary activity of human life.

Related Spinoza Articles:

Image source https://www.gornahoor.net/?p=14497

Check out Dr. Grant Maxwell's exclusive Beyond Belief interview here, where he continues his conversation on Spinoza and more.