Blood Libel in the UK

Blood Libel in the UK

11 min read

Before Gregorian chant, before Bach, there were the Levites. Explore how ancient Jewish music quietly shaped the entire Western musical tradition.

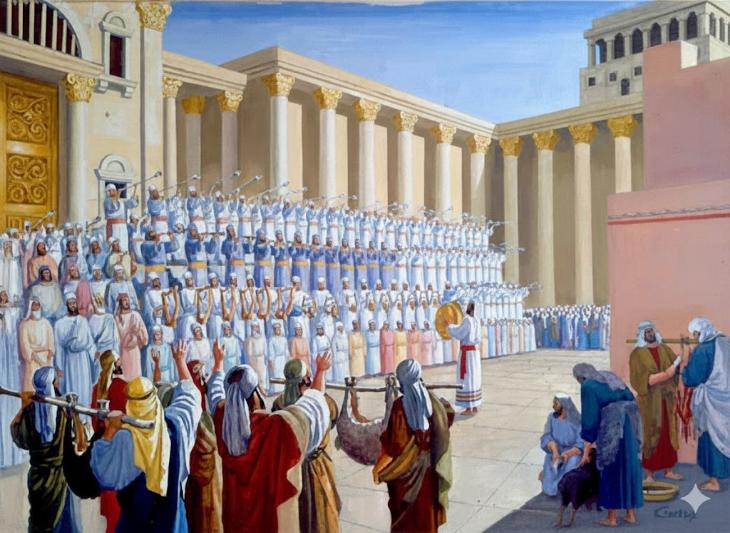

If we could travel back to the Jerusalem Temple two thousand years ago, we would find ourselves immersed in a breathtaking scene: hundreds of Levites, robed in white, chanting the Psalms of David as the Cohanim (Priests) offered the communal daily sacrifice. Surrounding them, master musicians filled the courtyards with the sounds of flutes, lyres, harps, cymbals, and drums—a musical pageant unmatched anywhere in the ancient world.

Could this sacred Temple music have anything to do with the rhythms and harmonies of modern popular music? Surprisingly, the connection may run deeper than most imagine.

The modern Western music we enjoy today did not emerge suddenly or in isolation. It is the product of a rich, 2,000-year tradition that unfolded gradually, each era adding new layers to what came before. Scholars and music historians widely note that music develops in an organic, cumulative manner, with every new style drawing on earlier forms.

“Music has long been viewed as an evolving organism, with each stylistic period growing out of the previous one.”

A good example comes from the distinguished American music theorist Professor William Ennis Thomson (1927–2019), former Dean of the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California. In his article “Music as Organic Evolution,” Thomson observes: “Music has long been viewed as an evolving organism, with each stylistic period growing out of the previous one. The modal systems of chant gave rise to tonality, which in turn enabled the harmonic complexity of the Baroque and Classical eras.”

Gregorian chant, or plainchant, is widely recognized as the oldest form of Western music. It is a monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song of the Roman Catholic Church, traditionally sung in Latin. Often called “the DNA of modern music,” Gregorian chant formed the foundation of Western song for a thousand years.

The key features of Gregorian chant include:

As the oldest form of Western music, chant’s influence was immense. Many scholars argue that much of our modern musical vocabulary originates in chant. More complex forms of Western music developed gradually from chant’s simple, meditative structures.

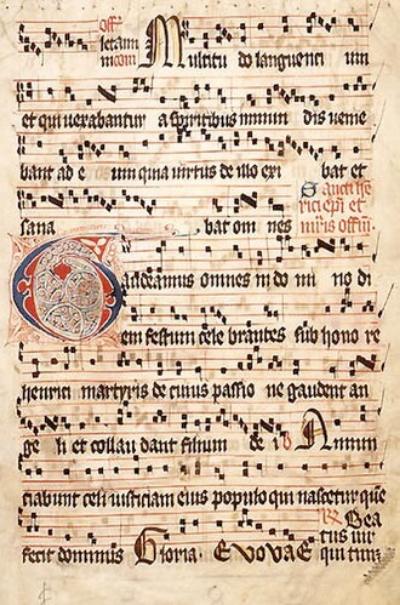

A Gregorian chant

A Gregorian chant

Associate Professor of Music at Stanford University and Editor of Sacred Music magazine, William Peter Mahrt, has long maintained that Gregorian chant is the foundation of the Western musical tradition, influencing everything from Renaissance polyphony to modern music. He emphasizes that chant’s modal systems and rhythmic freedom laid the groundwork for later developments in tonality and phrasing. As Mahrt writes, “Gregorian chant is the foundation of Western music – not only historically, but also structurally and aesthetically. Its modal system, rhythmic flexibility, and integration with liturgical text shaped the development of polyphony and the tonal systems that followed.”

How exactly did chant influence modern music?

But above all its effects, chant’s most significant influence was its modes. A mode is a sequence of notes with a specific pattern of spaces between notes. It was these Gregorian modes that evolved into the major and minor scales we use today. Most music scholars agree that modern music owes a profound debt to the ancient church modes, which shaped both melodic contours and harmonic foundations. These modes influenced Renaissance and Baroque music and continue to appear in jazz, rock, film scores, and even video game soundtracks.

Richard Taruskin—one of the most influential music historians of his generation and author of the monumental six-volume Oxford History of Western Music—notes: “The church modes provided the tonal framework for virtually all Western music until the rise of tonality. Even after, their melodic and harmonic residues continued to shape musical language.”

If Gregorian chant forms the foundation of modern Western music, then we must ask: where did chant itself originate?

Chant ultimately led to tonality. In modal chant, the music is meditative and open-ended; tonal music, by contrast, has direction. We hear tension and release, with melodies and harmonies moving toward resolution, giving the music emotional depth. Bach is widely considered the first fully tonal composer.

In the end, Gregorian chant was the perfect foundation for the growth of modern music. Its very simplicity created a stable musical framework that composers could build upon, experiment with, and ultimately transform into the richly varied musical tradition we know today.

If Gregorian chant forms the foundation of modern Western music, then we must ask: where did chant itself originate?

Many music scholars now recognize that Gregorian chant developed out of the Jewish chant traditions used in the Temple and in ancient synagogues.

“Christianity did not invent its musical forms ex nihilo; it absorbed and transformed the rich musical heritage of Judaism, especially in the realm of chant and prayer.”

Eric Werner, Professor of Jewish Music at New York University, was among the first scholars to conduct a systematic comparison of ancient Jewish and early Christian chant. His pioneering research was highly influential in establishing their shared origin in the music of the Jerusalem Temple. Werner’s landmark work, The Sacred Bridge, remains foundational in tracing Gregorian chant’s lineage to Jewish psalmody and cantillation. As he writes, “Christianity did not invent its musical forms ex nihilo; it absorbed and transformed the rich musical heritage of Judaism, especially in the realm of chant and prayer.”

John Harper, Professor of Music and Liturgy at the University of Bangor (UK), echoes this conclusion in The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy, noting that “Early Christian worship borrowed heavily from Jewish synagogue practice, including the chanting of psalms and scriptural readings.”

Similarly, Stanford University music scholar William Mahrt observes that “The Christian Psalm tones have their roots in ancient Jewish hymnody and psalmody.”

The shared origins of Gregorian and Jewish chant become clear when we examine their many striking similarities.

Psalm-Based Structure:

Gregorian chant is fundamentally rooted in the Book of Psalms—the same texts that formed the core of Temple worship and later synagogue liturgy.

Responsive Singing:

Ancient Jewish music employed antiphonal singing in the Temple, with two choirs alternating passages, as well as responsorial singing in the synagogue, where a cantor chanted verses and the congregation replied. Early Christian worship adopted these same techniques, and they became central to Gregorian practice, especially in the chanting of psalms and canticles.

A Cappella Tradition:

After the destruction of the Temple, a rabbinic decree prohibited the use of musical instruments in the synagogue as a sign of mourning. This helped shape a strong tradition of unaccompanied vocal music that continues in many Jewish communities today. Gregorian chant similarly developed as an a cappella tradition, performed without instrumental accompaniment.

Both traditions also employed recitation tones (fixed pitches used to chant extended texts), melodic cadences (formulaic phrase endings or transitions), and modal centering (anchoring melodies around a central pitch or finalis).

As is well known, Christianity began as an internal Jewish movement in the 1st century CE, and its founders and earliest adherents were all Jews. It is therefore not surprising that Christian liturgy has deep roots in Judaism and the synagogue. The Christian Bible itself acknowledges this connection, noting that Jesus and his disciples sang the traditional Hallel hymn after celebrating the Passover meal (cf. Mt 26:30; Mk 14:26).

Christian chant also inherited its foundational modal systems from Jewish music. Peter Wagner, Professor of Early Christian Music at Freiburg University (Germany) and a leading figure in chant scholarship, conducted influential comparative studies that helped establish the modal continuity between Jewish and Christian chant. As Wagner observed, “The influence of Jewish liturgical music on Gregorian chant is undeniable. The modal systems and melodic contours show clear parallels with synagogue traditions.”

Now that we have traced Western music back two millennia to the Jewish Temple, we can turn to the Temple’s own musical culture.

One of the highlights of the Temple service was the song of the Levites. They performed music twice each day—during the morning and evening daily sacrifice—and on holy days (Shabbat, the New Month, and festivals) they performed three times.

Illustration of Levites playing their lyres in the Temple.

Illustration of Levites playing their lyres in the Temple.

To qualify for Temple performance, Levites underwent rigorous musical training. The Temple itself housed a music academy with an extensive library. At age 25, a Levite was admitted into this academy, where he studied for five years. Only at age 30 did he begin to sing or play in the Temple. According to Chronicles 23:5, during the reign of King David the academy numbered no fewer than 28,000 Levites.

Following the destruction of the 2nd Temple in 70 CE and its replacement by the synagogue, the Temple's musical practices were adapted for the synagogue, shifting from animal sacrifices on the altar to one’s centered on prayer and chanting of Scripture.

Many former Temple Levites became teachers, cantors, and sages, helping to shape the prayers, piyyutim, and psalmody that define today’s synagogue worship. The Talmud mentions several Temple Levite musicians who later became contributors to synagogue worship, such as Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah mentioned in the Talmud (Arakhin 11b).

How central is music to Judaism? The Torah itself calls its teachings a song. “Now therefore,” God says to Moses, “write you this song, and teach it to the Children of Israel. Put it into their mouths, that this song may be a witness for me” (Deuteronomy 31:19–30). It is therefore no surprise that the Torah has always been both studied privately and proclaimed publicly through melody, using a standardized musical tradition.

The practice of chanting sacred texts such as the Torah was preserved through cantillation, a musical system consisting of roughly two dozen special accents placed above or below the words. Many scholars believe the cantillation marks and their melodies originated during Temple or Geonic times. Jewish tradition, however, ascribes them to Mount Sinai, when God gave the Israelites both the Written and Oral Torah.

After 2,000 years of global exile—during which Jewish communities became scattered across vastly different cultures—many have assumed that the original melodies were lost forever. In foreign surroundings, ancient chants absorbed local musical influences and eventually diverged into many distinct and sometimes bewilderingly different traditions. Over time, this diversity led some to doubt the authenticity of any surviving form.

Into this challenge stepped Professor Abraham Idelsohn, who from an early age dedicated himself to gathering and cataloguing every known strand of Hebrew chant preserved throughout the Jewish world.

Despite centuries of dispersion, Idelsohn argued that certain modal structures, melodic motifs, and cantillation patterns had remained strikingly consistent across communities—from Yemenite, Syrian, Moroccan, and Persian Jews to Ashkenazi and Polish traditions.

After years of tireless research, he completed his monumental Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies (published in ten volumes between 1914 and 1932). Using the shared musical elements found across these diverse traditions, Idelsohn sought to reconstruct the ancient, pristine melodies of the Temple.

Reviving these great foundational songs—and bringing them back to life for modern ears—may well be the challenge and calling of the musicians of our generation.

The story of Western music, when traced back through the centuries, may ultimately lead to the footsteps of the Levites in the Jerusalem Temple. From their psalmody and chant emerged the musical practices of the synagogue, which in turn shaped the earliest Christian liturgy and the Gregorian tradition that became the bedrock of Western music.

Far from being a forgotten relic, the Temple’s musical legacy continues to echo through the melodies, modes, and harmonies that define today’s musical world. As modern scholars and musicians uncover these ancient connections, we are reminded that the roots of Western music are far older, deeper, and more intertwined with Jewish history than most ever imagined. And perhaps, as we rediscover and revive the musical language of the Temple, we may yet hear again the timeless songs that once rose daily from Jerusalem’s holy courts.