Tom Stoppard’s Jewish Identity

Tom Stoppard’s Jewish Identity

8 min read

12 min read

4 min read

10 min read

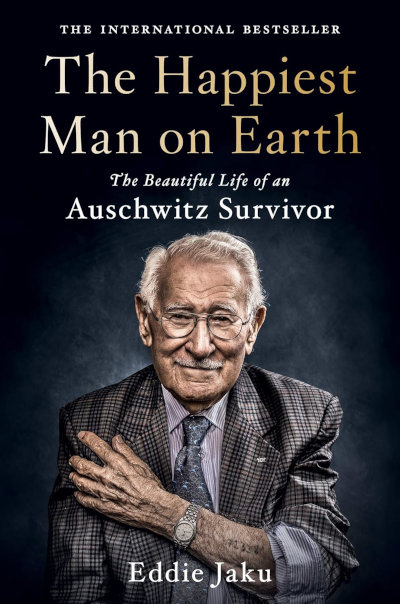

Eddie Jaku’s inspirational story of survival, forgiveness, and love.

Eddi Jaku survived Auschwitz and became a beloved humanitarian preaching love and forgiveness in his adopted country of Australia. Toward the end of his 101-year lifetime he delivered a Tedx talk “The Happiest Man On Earth” that has received 2,000,000 views on YouTube.

And he did all that after spending seven years as a prisoner in four concentration camps, escaping twice, sneaking back in once, and surviving a forced march that killed 15,000 prisoners.

Eddie Jaku showed us that hope can never fade away.

Abraham Salomon Jakubowicz was born into a Leipzig, Germany family of four on April 14, 1920. He had a happy childhood growing up with his parents, little sister Johanna, and Lulu, the family dachshund. His playmates called him Abie, which became Adie, and then Eddie. His engineering school education would serve him well during his lifetime, but it started off badly as he and other Jewish boys were kicked out of school when the Nazis rose to power.

Eddie (front right) with members of his extended family in 1932. He would be the only one to survive.

Eddie (front right) with members of his extended family in 1932. He would be the only one to survive.

His father orchestrated a new identity for him, so 13-year-old Abraham became “Walter Schleif” to hide his Jewish heritage and continue his study of mechanical engineering school in Tuttlingen, which was far south of Leipzig. Away from home, he stayed at an orphanage after classes. He graduated and earned an internship at a prestigious engineering union.

Abraham/Walter decided to risk a visit home and took a nine-hour train ride to see his parents and celebrate their 20th wedding anniversary. He called it “the biggest mistake of my young life.” He didn’t know his family had fled from the rising wave of antisemitic violence. Only their dog Lulu remained. He went to bed and at 5:00 AM on November 9, 1938, the door to his house was smashed in by ten Nazi soldiers. They beat him unmercifully, carved a swastika into his arm, and bayonetted Lulu to death. Abraham was taken outside and saw his neighborhood ablaze. He was forced to watch as his family’s 200-year-old house was burnt to the ground.

Kristallnacht. The Night of Broken Glass, had begun. Eddie wrote in his biography:

That night, atrocities were being committed by civilized Germans all over Leipzig, all over the country. Nearly every Jewish home and business in my city was vandalized, burned, or otherwise destroyed, as were our synagogues...as were our people. When the mob was done destroying property, they rounded up Jewish people - many of them young children – and threw them into the river that I used to skate on as a child. The ice was thin and the water freezing. Men and women I’d grown up with stood on the riverbanks, spitting and jeering as people struggled. “Shoot them!” they cried. “Shoot the Jewish dogs.”

He was loaded onto a truck and taken to Buchenwald and eventually put on a train to Auschwitz. Over the next seven dark years, he would serve time in four concentration camps.

In Auschwitz, he the number 172338 was tattooed on his arm. He learned that his parents had been victims of the Auschwitz gas chambers and crematoriums. Eddie slept naked in a narrow row of ten men when it was eight degrees below zero Fahrenheit. He marched for an hour and a half to work, sometimes clearing debris from a bombed-out ammunition depot or jackhammering coal on a 12-hour shift.

When his captors learned of his mechanical engineering background, he was made a foreman at the IG Farben chemical factory and was responsible for regulating air pressure to 200 machines. One of the company’s chief products was a poison gas used in the Nazi gas chambers.

One of the machine operators he ran into was his sister. They realized they couldn’t speak or even acknowledge each other in front of their captors. They passed each other in near silence daily.

He escaped once by hiding in a food drum and rolling off a delivery truck. Still dressed in his prison pajamas, he was freezing cold and stopped at a cabin for help. He was met by a Polish farmer and his rifle. The first five bullets missed him, but the sixth hit his left calf. He had to sneak back into Auschwitz where an old French doctor used an ivory letter opener and his fingers to dig and squeeze out the bullet. They timed the surgery to coincide with the bells ringing at a nearby Catholic church to muffle his screams of pain.

A teenaged Eddie (left) with his mother Lina, father Isadore, and sister Henni

A teenaged Eddie (left) with his mother Lina, father Isadore, and sister Henni

And what did he think of the man who shot him? “Do I hate that man? No, I do not hate anyone. He was just weak and probably as scared as I was. He let his fear overtake his morals. And I know that for every cruel person in the world, there is a kind one.”

By early 1945, the Russian troops were advancing, and the Nazi war effort was weakening. Auschwitz was evacuated and the Germans destroyed their gas chambers and crematoriums and forced the Auschwitz prisoners on a march into deeper German-occupied territory. Sixty thousand prisoners started this Death March and 15,000 perished during the march.

The surviving prisoners boarded a train to Buchenwald, and Eddie was assigned to a machine shop to make gears. By now, the Allied war effort was making solid advances against the Nazis, and Russian artillery and British bombing runs were heard daily. The prisoners were marched away from the advancing Russians to the east only to get closer to the advancing Americans to the west. Nazi soldiers began deserting their posts.

He escaped by crawling into a drainage ditch, then hid in caves eating snails and slugs. Near death, he was crawling down a highway and was met by an American tank. He weighed 28 kilograms, 62 pounds.

He wrote in his biography, “Those beautiful American soldiers. I’ll never forget. They put me in a blanket, and I woke up one week later in a German hospital. At first, I thought I was cuckoo, crazy, because yesterday I’d been in a cave, and now I was in a bed with white sheets and cushions, and nurses all around.”

Six weeks later, he was discharged and walked over the border into Belgium. He vowed never to return to Germany again. In Belgium, he spent time at a Jewish Welfare society where Jewish refugees and soldiers of the Allied armies would meet for meals and fellowship.

He found work as a precision engineer and soon was a factory foreman supervising 25 machinists. A local newspaper ran a story with photos of Holocaust survivors and his sister Johanna saw it. They were reunited and lived together in Brussels until she moved to Australia.

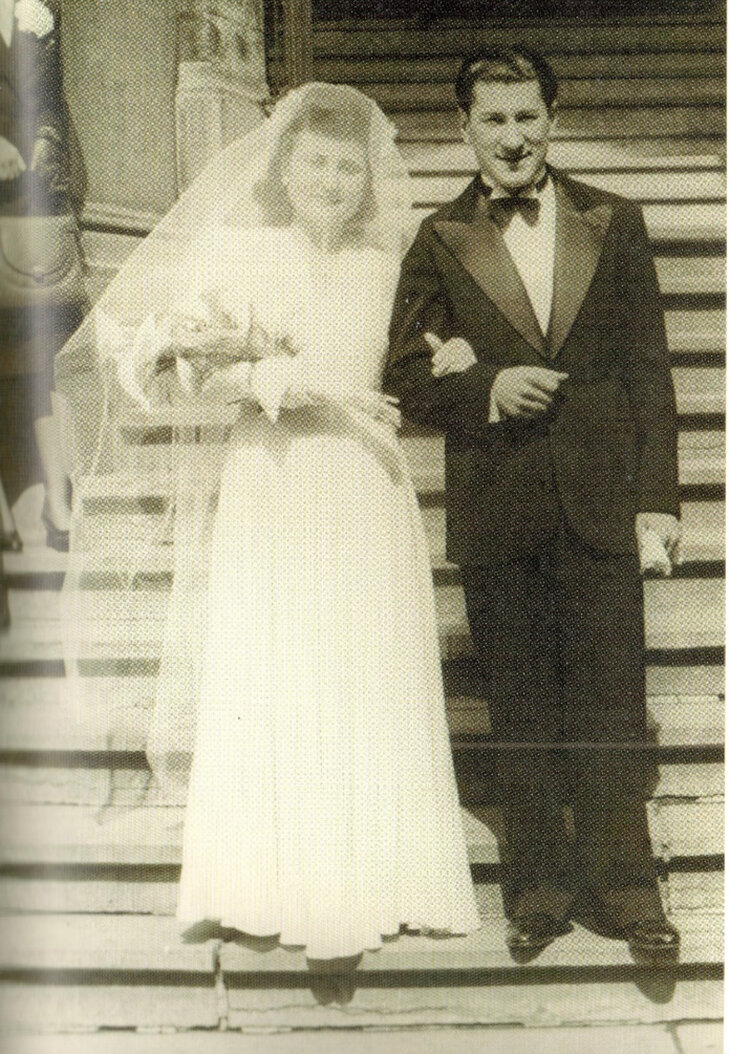

Flore and Eddie’s wedding day, April 20, 1946

Flore and Eddie’s wedding day, April 20, 1946

On April 20, 1946, he married Flore Molho, a Greek Sephardic Jew raised in Belgium. It would be a 75-year marriage. They met at the Town Hall in Brussels where she administered food stamps to him. A year later their son Michael was born.

“What a miracle to be alive and to hold my beautiful baby, my beautiful wife, If you had told me while I was being tortured and starved in the concentration camps that soon I would be so lucky, I would never have believed you. The greatest thing you will ever do is be loved by another person.”

“Each year, Flore and I celebrate our wedding anniversary on 20 April – Hitler’s birthday. We are still here; Hitler is down there. In my mind, this is really the best revenge, and it is the only revenge I am interested in – to be the happiest man on Earth.”

In 1950, the young family moved to Australia to join his sister, and he took a job at a medical instrument factory in Sydney. Soon he was in the automotive repair business and opened his own service station.

Next, he and Flore opened a real estate office, reclaimed his original name, and called the business E. Jaku Real Estate. Eddie and Flore worked there into their 90’s.

Slowly, Eddie began to speak about his years of brutal imprisonment. In 1972, he joined a group of 20 Holocaust survivors to create a meeting place. Ten years later, the Australian Association of Jewish Holocaust Survivors and Descendants was founded. Eddie was instrumental in the founding of Sydney’s Jewish Museum in 1992 and a separate organization exclusively for survivors in 2011.

In 2013, Eddie was awarded an Order of Australia Medal. On May 2019, he delivered a TEDx talk in front of a 5,000 people. His talk, “The Happiest Man on Earth” has been viewed two million times. Here are some key take-aways from his talk:

His 2020 biographical memoir “The Happiest Man on Earth” was an international best-seller.

Eddie Jaku died in Sydney on 12 October 2021, at the age of 101. His wife Flore died in Sydney on 6 July 2022, at the age of 98.

Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg mourned Eddie’s passing with an official statement, “Australia has lost a giant. He dedicated his life to educating others about the dangers of intolerance and the importance of hope. Scarred by the past, he only looked forward. May his story be told for generations to come.”

The New South Wales Jewish Board of Deputies wrote, “Eddie Jaku was a beacon of light and hope for not only our community, but the world. He will always be remembered for the joy that followed him, and his constant resilience in the face of adversity."

Sources

Many times you come across people who

Suffered great adversity in their lives & found ways to become positive people &have shown great Chizuk in overcoming life’s challenges. We have much to aspire to ! They are living legends . Tysm for this inspirational content!

May you go from strength to strength to strength

. Especially since there is a ripple effect …. Each person who reads it may pass it on to countless others . כל הכבוד !!!

This is an amazing inspirational book authored by an incredible man. Of many books on the Shoah I have read, this is easily one of the best. Having been to Auschwitz and other death camps as a former staff member on a the March of the Living years ago, his detailed descriptions of his days there were chilling. May his name be for a blessing.

It's a beautiful story. G-d bless his soul a"h.

The only ones to forgive the Nazis(may their name be erased) is the kaddisim, the ones that were murdered for kaddish Hashem, otherwise it is ok to be happy, some people that went through the Holocaust did not stay religious unfortunately, but you can't blame them unless you were in their shoes

What a wonderful story. It makes me proud to be a Jew and try and follow as "Eddie".

wow i have read a lot of survivor stories coming out of the holocaust but this one will stick out always. wow none of us should never have a day to complain compared to what Eddie this dear man went thru!!!

What a sweet, beautiful man. Seeing his kind face makes me cheeks wet.

Greatness, thank G!d!

Thank G-D - for the absolutely inspiring story.

IT'S ALSO TIME TO CELEBRATE THAT -THAT HE WAS BLESSED BY G-D - with all the attributes he needed to survive the horrors of capture - as others were blessed as well. Then - be able to tell the wonderful inspiring story - for others to hear - instead of keeping it hidden. May G-D - also inspire our current hostages - with the attributes they will need - to share their stories as well.

Have read his amazing book and tonight am going to see the play with the same title as his book!