A Jewish Look at Dan Brown’s The Secret of Secrets: Mystical Science Meets Jewish Wisdom

A Jewish Look at Dan Brown’s The Secret of Secrets: Mystical Science Meets Jewish Wisdom

8 min read

12 min read

4 min read

6 min read

A haunting new film revisits Elie Wiesel’s journey—from Auschwitz survivor to Nobel laureate—reminding us of memory, faith, and the duty to bear witness.

With the world watching the long-awaited release of the last remaining hostages, this moment invites reflection on the life of perhaps the most renowned Jewish prisoner of modern times—Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Prize–winning author and human rights champion whose searing memoir Night drew from his harrowing experiences in Nazi concentration camps.

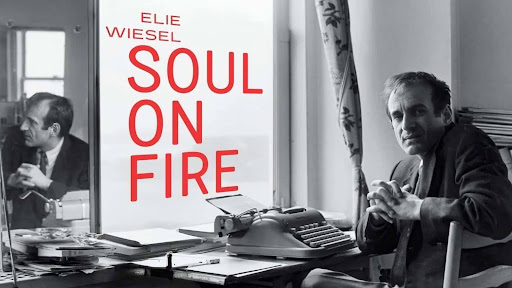

Wiesel’s extraordinary life—his imprisonment in Auschwitz-Birkenau, and later his remarkable rehabilitation and return to life—is the subject of the new documentary Soul on Fire, produced by filmmaker Oren Rudavsky together with Wiesel’s son, Elisha, and his widow.

Still a teenager when he and some 800,000 fellow Hungarian Jews were deported by the Nazi regime, Wiesel endured horrors that echoed the plight of hostages held in Hamas tunnels: starvation, cruelty, and suffering so severe it took him nearly a decade to begin processing it.

Wiesel and other survivors were urged to forget the past and rebuild. The postwar world had little interest in their stories—often left untold even within their own families.

Wiesel changed that.

Wiesel’s memoir Night transformed his concentration camp ordeal into a profoundly moving narrative.

Applying his eloquent literary voice to his own life, Wiesel’s memoir—completed in 1958 and published in English in 1960—transformed his concentration camp ordeal into a profoundly moving narrative. Night has since sold over ten million copies worldwide, including three million spurred by Oprah Winfrey’s 2006 endorsement.

While Night focuses on a single pivotal year, Soul on Fire traces the full arc of Wiesel’s extraordinary life, beginning with his Hasidic childhood in a small Hungarian city, where he was cocooned in the warmth of family and faith. The war shattered that world forever.

Life in a concentration camp was unbearable, yet in some ways returning to ordinary life proved even harder. Using stark black-and-gray animation, the film portrays a young Elie Wiesel, alone in Paris after his liberation in 1945.

“I felt nameless, ageless, faceless. I belonged to the world of the dead,” he recalls. Layered on top was crushing survivor’s guilt: “I was ashamed to still be here and not with the others who were no longer here.”

Photo by Bernard Gotfryd via Getty Images

In a one-room Paris apartment, Wiesel lived in isolation—single, working long days as a journalist, and spending time with street people whose desperation mirrored his own. Like so many survivors, he kept his tragic story buried deep. But over time, he came to see himself as a “witness,” entrusted with the sacred duty of telling the world what he had seen.

Wiesel described his instinct to write as “intuitive.” “I’d wake at four a.m. and go to the page,” he recalled. For him, writing was like “carving words on a tombstone” to tell his parents—turned to ash—that he loved them. It also became a way to commune with the dead: “Whenever I write, I feel my grandfather and mother looking over my shoulders.”

For him, writing was like “carving words on a tombstone” to tell his parents that he loved them. It also became a way to commune with the dead.

His first manuscript was an 864-page Yiddish volume titled And the World Was Silent. “It pointed the middle finger at the world,” notes scholar Naomi Seidman in the film. Wiesel explained, “I wrote it for other survivors, to tell them they must speak.” Another force driving him was the early rise of Holocaust denial. Barely a decade after the crematoria flames were extinguished, he was already seeing the memory of the Jewish genocide begin to fade.

Published only in Argentina, that first book sold very few copies.

After that first book, Wiesel pared down his words. In Night, instead of indicting the non-Jews who allowed Jews to be slaughtered, he turned his anger and disappointment toward God. In the film, he describes his relationship with God during those early postwar years as “deeply wounded.” That rupture shaped every aspect of his life—throughout the first two decades after the war, he refused to marry or have children.

But this would change. In 1969, at a Manhattan dinner party, Wiesel met Marion Erster. Not long after, the two were married in Jerusalem’s newly liberated Old City. Their marriage became a turning point, a source of healing and renewal for Wiesel.

“Elie became more religious,” Marion recalls. The film shows him wrapped in tallis and tefillin. Though not highlighted on screen, Wiesel also sustained deep friendships with Jewish leaders, including the Lubavitcher Rebbe and Rabbi Menashe Klein, the noted halachic authority he had known since childhood.

At the same time, Wiesel began raising his voice as a global human rights advocate. The documentary devotes considerable attention to his protest of President Ronald Reagan’s planned visit to the Bitburg cemetery in Germany, where 30 Waffen-SS soldiers were buried. The visit was scheduled soon after Wiesel received the Congressional Gold Medal, awarded for his contributions to Holocaust remembrance and human rights.

His tireless advocacy culminated in the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize, which hailed him as “a messenger to mankind” for his call to peace, atonement, and human dignity.

Instead of simply thanking the president for the honor, Wiesel issued a gentle yet unflinching appeal—addressing Reagan as a friend—to reconsider. It was a controversial and risky move: prominent Jewish leaders had urged him to stay silent. Reagan ultimately went ahead, but Wiesel had fulfilled his mission. “He made people think about why they are here in terms that touched them,” Marion observed.

In the decades that followed, Wiesel continued to speak out: against South African apartheid, the genocides in Rwanda and Bosnia, and on behalf of Soviet and Ethiopian Jews. His tireless advocacy culminated in the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize, which hailed him as “a messenger to mankind” for his call to peace, atonement, and human dignity.

What might Wiesel have said about today’s challenges? Perhaps the answer lies in the mystical teachings he often loved to quote: “Any person can bring the Messiah.”

The film closes with Wiesel’s haunting voice singing Ani Maamin—the Jewish declaration of faith in the Messiah’s imminent coming. His mournful yet steadfast embrace of those words echoes the stories of Hamas hostages who clung to Jewish prayers as mantras of survival. Perhaps that is the message we too must hold close, as the hostages return home.