Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

8 min read

Mindful of the pledge I made to our murdered relatives and friends, I know I've done far too little.

In 1936, my parents, Joseph and Marianne Klein, emigrated with their three daughters from Frankfurt/Main to Amsterdam. We settled in the same neighborhood as Anne Frank’s family, whom we had known in Frankfurt. Margot Frank, Anne’s older sister, was among the first four thousand Jewish refugees aged sixteen to forty ordered to report for “forced labor” in Germany. My older sister was served the same summons. Anne had just turned thirteen, I was almost fifteen, and my younger sister twelve, all three of us too young under the edict to be sent away.

It is well known from Anne’s diary that the day after Margot received the summons, the Frank family went into hiding in the back quarters of Otto Frank’s business premises. They managed to hold out for 25 months, thanks to the loving care of Mr. Frank’s clerical staff and to the unwavering support of his business partners. Anne wrote vividly about their secret life above the office and warehouse rooms.

My sisters and me early spring 1942

My sisters and me early spring 1942

Sadly, Otto Frank was the only one in the family to survive the war. Anne and Margot died from typhus at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and Mrs. Frank succumbed to exhaustion in Auschwitz. Upon his return to Amsterdam, despite his tremendous loss, Mr. Frank was happy to find that his business partners and his office staff had survived the horrors, and that my family still lived in the same apartment where he had last visited us three years before.

Thanks to a little-known lawyer named Hans Calmeyer, my family and thousands of other survived.

"How did you escape the dance of death?" he asked at the time, a question repeated again and again whenever I speak about the Holocaust. The answer is that there were other “good” Germans besides Oskar Schindler with his now-famous list. Thanks to one of them, a little-known lawyer named Hans Calmeyer, my family and thousands of other Jews survived.

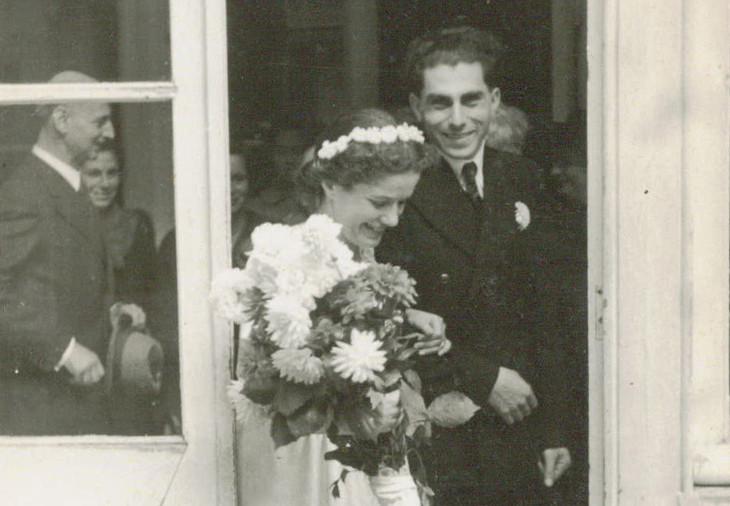

At our wedding in 1947, with Otto Frank in the background

At our wedding in 1947, with Otto Frank in the background

Although he never joined the Nazi party, Calmeyer was put in charge of adjudicating “dubious cases,” that is, cases where petitioners claimed that they had less “Jewish blood” than their papers said. By bending the existing racial laws in favor of the petitioners as much as he possibly could, Calmeyer was able to remove around 3700 people from the deportation list. My maternal grandmother was not Jewish. With the help of a Dutch lawyer we were able to devise a convincing story purporting that my mother’s father had not been Jewish either. Calmeyer allowed himself to be convinced and my mother, sisters and I could shed our yellow stars and blend in with the rest of the population. My father had to keep wearing his star, but the fact that he lived in a “privileged mixed marriage” protected him from deportation.

Hans Calmeyer

Hans Calmeyer

Thousands of others were similarly saved by Calmeyer’s favorable decisions which he rendered at great peril to himself, since the German secret police kept looking over his shoulders and made frequent attempts to denunciate him. Except for a brief citation by Yad Vashem published in 1992 when Hans Calmeyer was declared “a righteous man among the nations,” there is nothing about him in English, so I felt the urgent need to fill the gap. Ursula LeGuin and other writer-friends persuaded me to weave the story of my own survival and that of my boyfriend and later husband, Rudi Nussbaum, into my book. The two of us had been close ever since he was 19 and I was 14, when he went underground into hiding and I became his liaison person with the above-ground world.

In the book I tell about the stimulation and the special tensions that early commitment brought into my life as a teenager. Rudi’s parents were among the 108,000 Jews deported from the Netherlands and I was the only one close enough to him to give him emotional support. His attempt to flee to Spain across the Pyrenees forms an especially exciting section of the book.

My family was very conscious of the fact that we were extremely lucky to be able to stay in our Amsterdam apartment. We sent food packages to our Jewish friends and neighbors, while they were still in a transit camp on Dutch soil, and I also tried to bring comfort and cheer to a Jewish couple hidden in our neighborhood. My high school years coincided exactly with the war. During the notorious “hunger winter,” the last winter of the war, I was a senior preoccupied with scrounging up food for the family.

We felt the victims calling out to us: “Make sure this kind of mass slaughter will not happen again. Don’t be bystanders."

After the war, the exhilaration of being free again was soon replaced by the deeply depressing realization that Rudi’s parents and our other relatives and friends would not come back from the concentration camps. Both of us felt that the victims were calling out to us: “Make sure this kind of mass slaughter will not happen again. Don’t be bystanders. Get involved in memory of us, for the sake of mankind!” Both of us pledged to do just that.

I tried my hand as a fledgling journalist. But I soon found out that I had to toe the line as to what was within the paper’s political predilections. Consequently, I decided to go to college to acquire knowledge and an advanced degree, so people would have to publish what I write (it was not quite as simple as that).

Rudi and me with our three children in front of our Portland house, with my mother

Rudi and me with our three children in front of our Portland house, with my mother

Rudi, who had lost nine years of education by double emigration (first to Italy, then to the Netherlands) and by spending almost four years in hiding, still needed to get his high school diploma, which he did at age 24. In record time, he managed to acquire a PhD specializing in nuclear physics, a very hot field in the mid-20th century. We got married in 1947 and Otto Frank, Anne’s father, was Rudi’s best man. I worked and took care of our children, till we ventured across the Atlantic in 1957 and eventually settled in Portland, OR. I went back to school even while teaching part time and raising our three children. It took close to 20 years before I finally got my PhD in German Language and Literature and started a regular academic career.

Over the years, Rudi and I had not forgotten the silent pledge we had made to our Jewish relatives and friends murdered by the Nazis. We both were active in the peace movement. We acquired our US citizenship so we could protest and demonstrate. Rudi got deeply involved in anti-nuclear work with people who have lived down-wind from the Hanford Nuclear Reservation and I helped him set up research that substantiated the claim that their health had been compromised by low level nuclear radiation.

In my own field of 20th century literature, I specialized on the works written by authors of Jewish background who had fled Hitler’s Germany to the Netherlands. Among these was Grete Weil, whose husband was murdered by the Nazis. She wrote poignantly in her semi-autobiographical post-war novel Generationen: “I suffer from Auschwitz, like others suffer from TB or cancer. I’m as hard to live with as other sufferers.” Another focus of my attention were the different versions of The Diary of Anne Frank, of which far too few people are aware.

Meanwhile, Hans Calmeyer had returned to his home after spending 16 months in a Dutch prison for having been part of the German occupying government. After the war, back in his home city of Osnabrück where he practiced law, Hans Calmeyer soon realized that he could do very little to help steer war-ravaged Germany towards true democracy. Rather than feeling proud of his rescue action in the Netherlands, he identified more and more with the Nazi victims he had not saved.

Rudi and me in 2008

Rudi and me in 2008

In 1965, he read Ashes in the Wind: The Destruction of Dutch Jewry, by the eminent Jewish-Dutch historian Jacob Presser. Calmeyer devoured the original Dutch edition fresh from the press. In his chronicle Presser devotes a chapter to Hans Calmeyer in which he has unequivocal praise for Calmeyer’s rescue mission. Instead of feeling relieved, Calmeyer wrote a letter to the historian in which he shares Presser’s recognition that any well-intentioned action fell short and concludes that each supportive response was “too little, too little!”

Over the years, Calmeyer turned more and more into a recluse. After he had suffered a mild heart attack in 1971, he felt that his death was near and he was ready to go. He died the next year at age 69.

Aware of the dismal state of our world almost 75 years after the end of World War II and mindful of the silent pledge I’d made to our murdered relatives and friends, I know I have tried to fight the bad and support the good, but it, too, has been too little, too little!