An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

6 min read

After fleeing the Nazis, many Hasidic Jews settled in Samarkand, alongside the centuries-old Bukharan Jewish community when the communists ruled the region.

In the 1940s, as World War II raged on in Europe and Hitler was sending Jews to the death camps, many members of the Hasidic Lubavitch community found a place of refuge: Samarkand, a city in Uzbekistan. They settled alongside Bukharan Jews, one of the oldest ethno-religious groups in Central Asia.

Though these Jews were safe during the war, when the Soviets took over afterwards, communism forbade people from practicing their religion. If they were caught, they could be sent to prison, a forced labor camp, or worse.

That didn’t stop the Hasidic Lubavitch community there, who continued to practice their Judaism under the ever-present eyes of the KGB at a time when a majority of Jews were forced to give it up.

In Rabbi Hillel Zaltzman’s new book, “The Jewish Underground of Samarkand: How Faith Defied Soviet Rule,” readers can learn about how the Jewish community continued to survive – and even thrive – in the face of possible persecution.

In 1943, Zaltzman, then only four years old, fled Ukraine with his family when the Germans were invading. Like many fellow Lubavitchers, they found safety in Samarkand, but it wouldn’t last long.

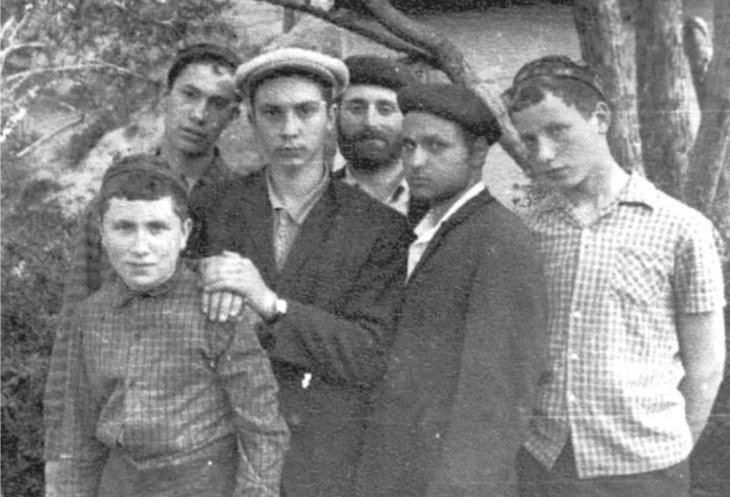

Students of the underground yeshiva in Samarkand: From left to right: Avrohom Zerach Notik, Tanchum Boroshansky, Yosef Yitzchak Zaltzman, Benzion Goldschmidt, Shmuel Notik

Students of the underground yeshiva in Samarkand: From left to right: Avrohom Zerach Notik, Tanchum Boroshansky, Yosef Yitzchak Zaltzman, Benzion Goldschmidt, Shmuel Notik

When the communists took over, they infiltrated and controlled every aspect of life, from the synagogues to the schools, where Jewish boys and girls would typically learn about Jewish rituals.

In his book, Zaltzman writes, “The war for Jewish education was both offensive and defensive: Parents struggled to keep their children from attending the Soviet schools, or at the very least to keep them home on Shabbos and holidays, if they were forced to attend at all. At the same time, they tried to provide their children with an authentic Jewish education at home.”

The fathers would go to work and the children would stay home with their mothers and receive a Jewish education. But it wasn’t so simple.

“[Mothers] were the ones who were left alone with their children while their husbands went to work, and every knock on the door brought with it a rush of fear and anxiety,” Zaltzman writes. “Unfortunately, the tremendous stress had a detrimental effect on the health of many of these heroic women.”

Zaltzman’s family, as well as other Jews, had special codes for communicating, like how to knock on a door or ring a bell to signal that it wasn’t the KGB. The codes were used when Jews were learning or conducting any sort of religious activity.

Eventually, Zaltzman himself had to go to public school because of threats from a local principal. “If my father did not send me to school, warned the principal, his rights as a parent would be revoked,” he writes. “I would then be sent to a government orphanage.”

Jewish boys who studied Torah in the Underground classes

Jewish boys who studied Torah in the Underground classes

His father registered him in a school in a mostly Muslim district where he hoped nobody would notice when he wasn’t in school on Shabbat or the Jewish holidays. In school, the students had to sing songs praising Father Stalin, Lenin, Mother Russia, and the Communist Party, but he didn’t want to.

Once, his teacher noticed and asked him why he didn’t sing. Without thinking, he replied, “I don’t like your songs.”

He then realized that he had made a huge mistake. The teacher said, “What do you mean by ‘your songs’? Which songs are ‘ours’ and which songs are ‘yours’? Go over to the blackboard and sing one of ‘your’ songs!”

Zaltzman recalled some Azerbaijani music that a neighbor played in his housing district. He’d heard these songs so many times that he knew them by heart.

“As I began to sing, the teacher opened her mouth wide in surprise,” he writes. “She had not imagined that I was able to sing so nicely! She enjoyed it so much that she completely forgot my faux pas, or perhaps she thought that I had been referring to Azerbaijani music all along.”

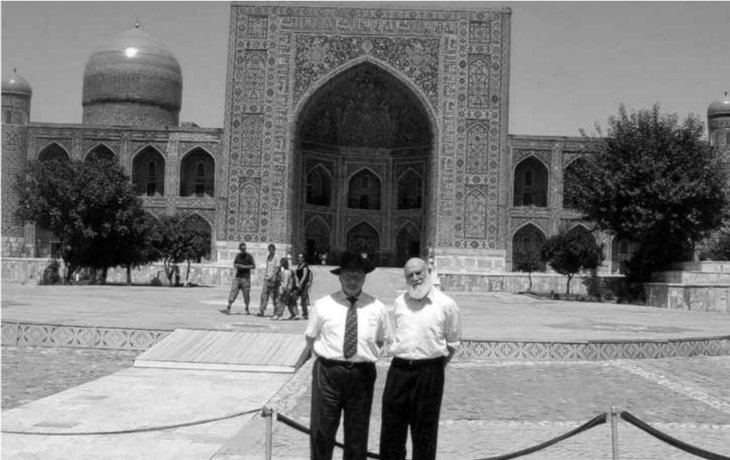

Revisiting Samarkand: The author and his brother, Berel, in Registan Square, Samakand's main tourist attraction, in the heart of the Old City

Revisiting Samarkand: The author and his brother, Berel, in Registan Square, Samakand's main tourist attraction, in the heart of the Old City

“The Jewish Underground of Samarkand: How Faith Defied Soviet Rule” is full of stories about close calls and the obvious miracles the Jews of Samarkand experienced.

For instance, only a few elderly Jews would go to the official synagogues of Samarkand because there were always KGB spies there. Children weren’t allowed to go, and most adults were afraid of the government and wouldn’t attend, either. Secret services were held without Torah scrolls.

“Our greatest challenge was obtaining a Torah scroll,” Zaltzman writes. “We did not possess one of our own, and had no way to get hold of one. Asking the gabbai of the shul would no doubt be our undoing, as the authorities would thereby instantly discover our activities. Taking one without authorization was also risky; sooner or later the ‘burglary’ would be discovered and the ensuing commotion would quickly lead the government to our activities. Often enough, we had to suffice with reading the weekly Torah portion from a printed Bible, if only to preserve the structure of the service and not forego the Torah reading altogether. That was the best we could do.”

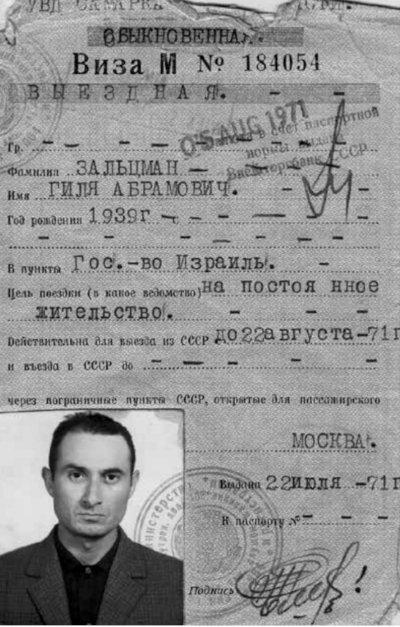

After World War II ended, some Jews in Samarkand snuck out of Uzbekistan and went back to where they came from, like Poland. But it was very risky to leave – if the KGB caught one of them trying to flee without the government’s permission, it could mean a harsh punishment like imprisonment (or worse). Zaltzman’s family didn’t want to take any chances. (The Soviets almost never granted permission for people to leave until 1990, after Gorbachev came to power and he instituted the policy of glasnost, which allowed for some Jews to finally get out.) After 15 years of waiting to obtain a visa, in 1971, his wish was finally granted, and Zaltzman went to Israel, where he had relatives.

The exit visa for which the author waited fifteen years

The exit visa for which the author waited fifteen years

From Israel, he worked with the Jews in Samarkand from afar through his organization Chamah. He helped to provide services to the community there, such as a soup kitchen for the needy, meals-on-wheels for the elderly, and therapy for children with special needs. In 1973, he moved to the U.S. to start a branch of Chamah there, and today, he resides in Brooklyn, continuing his work.

Today, there are almost no Jews in Samarkand. Many of them made aliyah to Israel, while others immigrated to the U.S. and elsewhere when the Iron Curtain finally fell. Zaltzman has been back three times since he left because his mother is buried there.

Zaltzman hopes his book will inspire a generation of younger Jews. “It is crucial for the younger generation to understand that observing Judaism is not solely about freedom, but also about persevering through hardships,” said Zaltzman. “I hope this story encourages people to uphold their Jewish identity in all circumstances.”

Where can I find an English language copy of this book? Steve Finer stevenedwardfiner@yahoo.com

https://www.amazon.com/Samarkand-Far-Reaching-Rabbi-Hillel-Zaltzman/dp/0989443825

It is amazing in Samarkand the Jews risk their life to go Shabbat service in the USA people are free to go but most of them don’t

Inspiring! What a contrast to today’s apathy.