When Ms. Rachel "Likes" Antisemitism

When Ms. Rachel "Likes" Antisemitism

9 min read

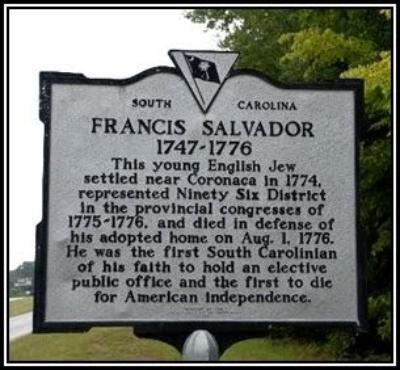

The forgotten story of Francis Salvador, the Jewish Founding Father of America.

In the summer of 1776, as revolution ignited across the American colonies, a young Jewish immigrant rode headlong into history.

He was 29 years old. Born into immense wealth and privilege in London, he had every reason to remain safely on the sidelines of the rebellion. Instead, he chose the opposite path: the untamed frontier of South Carolina, a radical political experiment called liberty, and a war whose outcome no one could yet predict.

His name was Francis Salvador.

Salvador became the first Jew to hold elective office in the Americas and the first Jew to die for the American Revolution.

Long before Jewish participation in American public life was taken for granted, Salvador shattered expectations. He became the first Jew to hold elective office in the Americas, a fierce advocate for independence when loyalty to the British Crown was still the safer choice, and ultimately the first Jew to die for the American Revolution.

Yet his story is almost unknown.

Salvador was a bridge between worlds. A Sephardic Jew whose family fled the Inquisition. An English aristocrat who rejected empire. A legislator who fought as a common soldier. He believed at great personal cost that the American “experiment in liberty” was not just a political gamble, but a moral calling.

His life would last less than three decades. But in those years, Francis Salvador helped lay the foundations of a nation that promised a place where faith and freedom could coexist.

The story of Francis Salvador begins in the highest echelons of London’s Sephardic elite. The Salvador family (originally Rodrigues-Salvador) were descendants of Sephardic Jews who had fled the 15th Spanish Inquisition to find refuge in Amsterdam and later in London.

By the mid-1700s, they were one of the wealthiest Jewish families in the British Empire. Francis’s grandfather, Joseph Salvador, was the first Jewish director of the East India Company and a pillar of the Bevis Marks Synagogue. They lived in a world of private tutors, continental tours, and aristocratic connections.

The Bevis Marks Synagogue

The Bevis Marks Synagogue

However, a series of global calamities struck the family fortune. The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755—which Francis’s grandfather survived—decimated their Portuguese holdings. Later, the failure of the Dutch East India Company and shifts in the British market drained the family coffers.

Francis, then 26 years old, found himself in a position many Jews have faced throughout history, looking toward a distant horizon in search of a new country to rebuild in.

Fortunately for Francis, his grandfather, Joseph Salvador, already prepared a plan B years earlier. In 1755, when Francis was still a young boy, Joseph purchased 200,000 acres of land in the South Carolina backcountry (an area later known as the Ninety-Six District) as a speculative investment and a potential refuge for Jews fleeing persecution and poverty in Europe. Little did Joseph know that his own grandson would be the first one to flee there.

Jewish investors purchasing large tracks of land was a novel concept at the time, since Jews were historically barred from land ownership in European countries. But the colonies of the New World prioritized economic growth over religious restrictions, and so laws against Jewish land ownership were non-existent or rare.

In late 1773, Francis left his wife and children in London, carrying with him a deed to only a fraction of his family’s property in the Americas; 7,000 acres of frontier land in the Ninety-Six District of South Carolina, a tract that later became locally known as "Jews’ Land”. After a long transatlantic voyage (before steamboats were invented), Francis landed in Charleston, trading his life as a London aristocrat for the rugged isolation of the American frontier.

He settled on his family’s plot of land near Coroneka Creek, where he established a plantation he named "Cornacre”. Far from a manor house, his residence was a functional home designed for the harsh "Upcountry" environment, where he focused on cultivating Indigo, a profitable but labor-intensive crop used for blue dye.

Coat of Arms of Francis Salvador

Coat of Arms of Francis Salvador

Though he was the only Jew in the region, he quickly gained the respect of his neighbors, specifically Major Andrew Williamson, who became his close friend and mentor in frontier survival. Wealthy planters of the South Carolina backcountry, men like John Rutledge and Charles Pinckney, were struck by his education, his polished manners, and his fierce intellect.

Francis Salvador's primary goal was to stabilize the plantation and prove its financial viability so he could send for his wife, Sarah, and their four children (a son and three daughters) still in London. He wrote to them with great hope, envisioning a future where they would be reunited in the land of opportunity.

In December 1774, the residents of South Carolina’s Ninety-Six District did something almost unthinkable: they elected Francis Salvador to represent them in the First Provincial Congress. To understand why this was revolutionary, one must first understand the law.

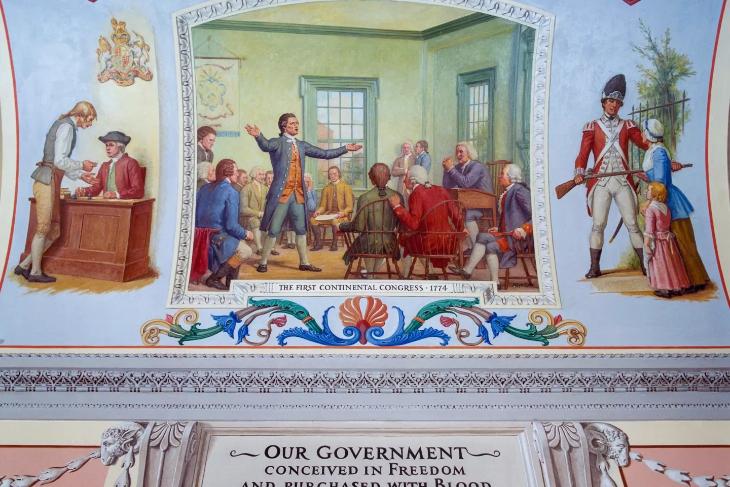

Painting by Allyn Cox

Painting by Allyn Cox

Under British common law (including in the American colonies), Jews were legally barred from voting or holding office. Yet, in a display of what would later become the American spirit, his neighbors simply ignored those statutes. They saw a man of character and integrity, and they chose him to be their local leader. Francis became the first professing Jew to represent the masses in a popular assembly in the modern world.

As a member of the Congress, Francis wasn't just a "token" representative. He was a powerhouse. He helped draft the state’s first constitution and served on committees to procure ammunition and assess the security of the frontier.

Most importantly, he was a vocal advocate for total independence. At a time when many were still hesitant to break with the King, Francis Salvador, the man born into the British aristocracy, urged his fellow colonists to cast their lot with the dream of a new, free, and independent nation.

In 1776, the British High Command devised a strategy to crush the American Revolution from within. They encouraged their Native American allies, the Cherokee, to attack frontier settlements, hoping to force the Patriot militias to abandon the coast in order to protect their families further inland.

A messenger arrived at Francis Salvador’s plantation with news that a Cherokee war party was sweeping through the district. Salvador sprung into action.

On the morning of July 1, 1776, just three days before the Declaration of Independence was signed in Philadelphia, the frontier erupted. A messenger arrived at Francis Salvador’s plantation with news that a Cherokee war party was sweeping through the district. What Francis Salvador did next earned him the title "The Jewish Paul Revere”.

Without hesitation, he leaped onto his horse and galloped 28 miles across the rugged terrain to the plantation of Major Andrew Williamson. Along the way, he shouted warnings to the settlers, many of whom were unarmed and unaware of the impending danger. His ride allowed the local militia to organize and save hundreds of lives from the initial onslaught.

But Francis didn't stop at sounding the alarm. He personally joined the militia as a private, refusing to hide behind his legislative status. He spent the next month on the front lines, fighting in the dense forests and swamps of the South Carolina interior.

On the night of July 31, 1776, Major Williamson’s force of 330 men was moving toward the Keowee River. In the pitch black of night, they were ambushed by a combined force of Loyalists and Cherokee warriors. Salvador was riding at the front of the column. In the first volley of gunfire, he was hit three times. He tumbled from his horse and into the high grass of the bushes.

In the chaos of the night, a soldier found him. Salvador was scalped while still alive. When Major Williamson finally dislodged the enemy and found his friend in the dark, the scene was gruesome.

Williamson recorded the moment in his memoirs. Salvador, bleeding out and near death, asked one final question: "Have we beaten the enemy?"

Williamson replied, "Yes."

At just 29 years old, Francis Salvador became the first Jewish soldier to fall in the American Revolution.

Salvador whispered that he was glad to hear it, shook the Major’s hand, and died 45 minutes later. He never saw his wife or children again. At just 29 years old, Francis Salvador became the first Jewish soldier to fall in the American Revolution.

Although the Declaration of Independence took place nearly a month prior to his death, most Americans didn’t hear the news for weeks. Word travelled slow, especially in frontier zones like rural areas of South Carolina, and communication devices like telegraphs and same-day distribution systems hadn’t been invented yet. It’s not clear to historians whether or not Francis Salvador died knowing his vision of freedom and liberty had already been realized through the establishment of the United States.

Why has Francis Salvador been relegated to a footnote in history? Perhaps it is because he died on the frontier, early on in the war, far from the dramatic stage of Philadelphia. Perhaps it is because his family remained in London, and his line did not continue as a "founding family" in America.

But for Jews around the world, Salvador’s story contains a vital spark of wisdom: the most important choices in life are made without guarantees. He committed himself to a cause that had no clear ending, no promise of success, and no assurance that history would remember him. Independence had not yet been declared (or was not yet known), victory was far from certain, and the cost was real and immediate. Yet he acted anyway.

With great courage, Frances Salvador chose to risk his life for his principles when success was nowhere in sight.

In the heart of Charleston, South Carolina, tucked away in Washington Park, stands a humble granite memorial with the following inscription:

In the heart of Charleston, South Carolina, tucked away in Washington Park, stands a humble granite memorial with the following inscription:

"Born an aristocrat, he became a democrat. An Englishman, he cast his lot with the Americans. True to his ancient faith, he gave his life. For new hopes of human liberty and understanding."

The next time you think of the Founding Fathers, remember the young Sephardic Jewish immigrant who helped give birth to a new nation.