Marty Supreme, Jewish Pride and the American Dream

Marty Supreme, Jewish Pride and the American Dream

4 min read

Through his Catalan Atlas, Abraham Cresques charted not just geography, but a vision of faith, wisdom, and harmony that still speaks to our world.

My sense of direction is terrible and I rely heavily on Google Maps. Today's maps tell you exactly what to expect if you wander from the safety of your couch. In the medieval world, maps often played a different function. Their cryptic lands populated by fantastical beasts and popular legends were meant to convey the mystery and danger of what lies beyond the familiar.

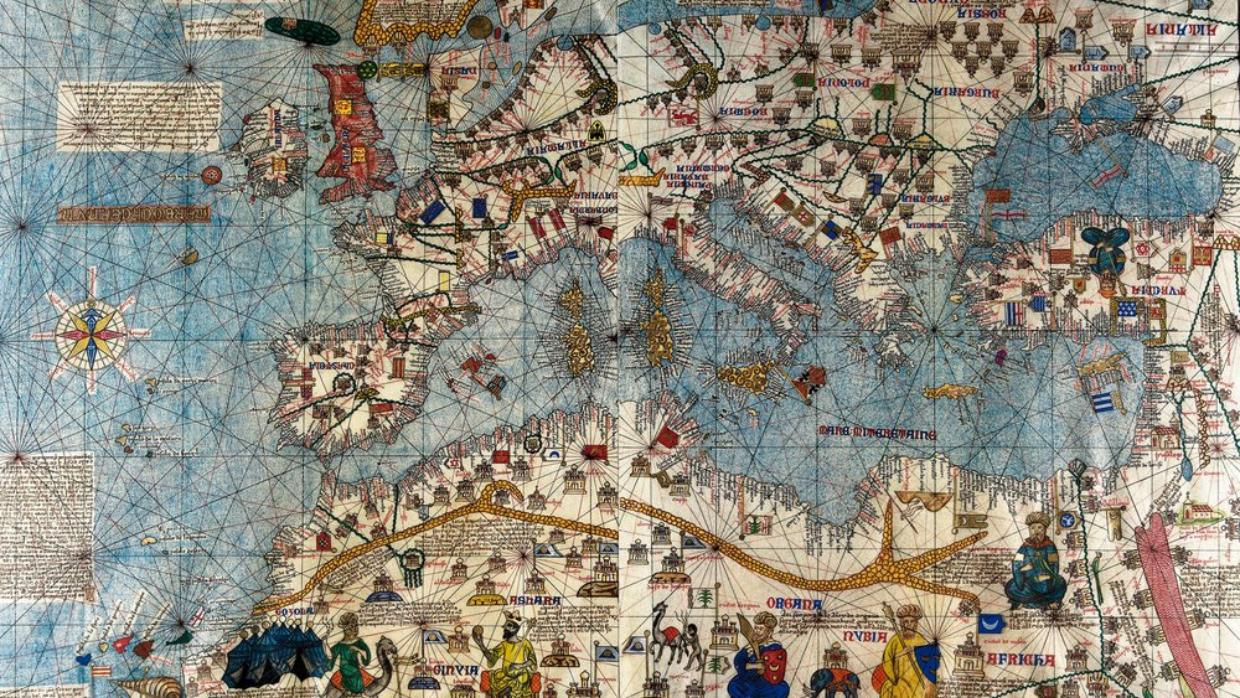

But in 1375, on a small island in the Mediterranean, a Jewish craftsman attempted a balance between accuracy and awe. His name was Abraham Cresques, and his Catalan Atlas would become one of the most influential maps of the Middle Ages.

Cresques lived in Palma, Majorca—a crossroads of merchants, sailors, and scholars. Known as a “master of maps and compasses,” he was fluent in the sciences and languages that passed through the ports of the Mediterranean. His patrons were Christian kings but his sources were global: Jewish astronomy, Islamic geography, and travelers’ reports from as far as China.

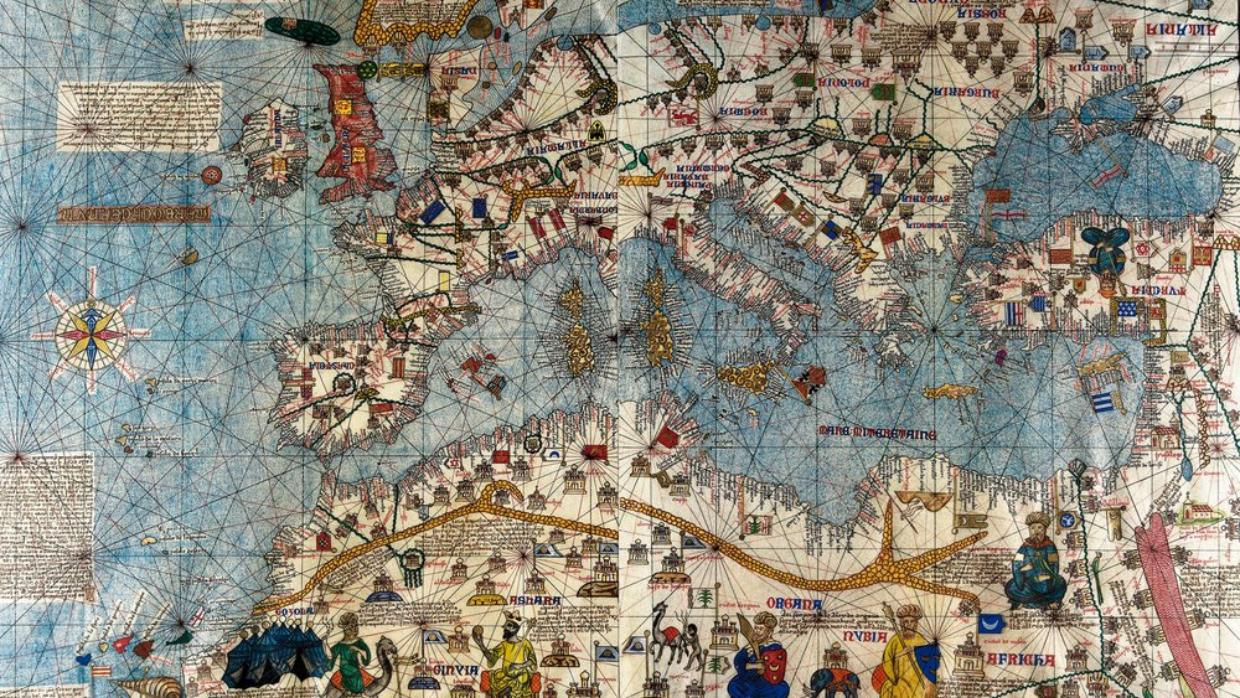

Many medieval maps were more statements of faith than science. They were meant to teach a worldview, not help a traveler find his way. Cresques's era saw a movement towards precision and utility, and yet his Catalan Atlas did not abandon its medieval roots. It joined the accuracy of new navigational data with the wonder of the stories people told about the world.

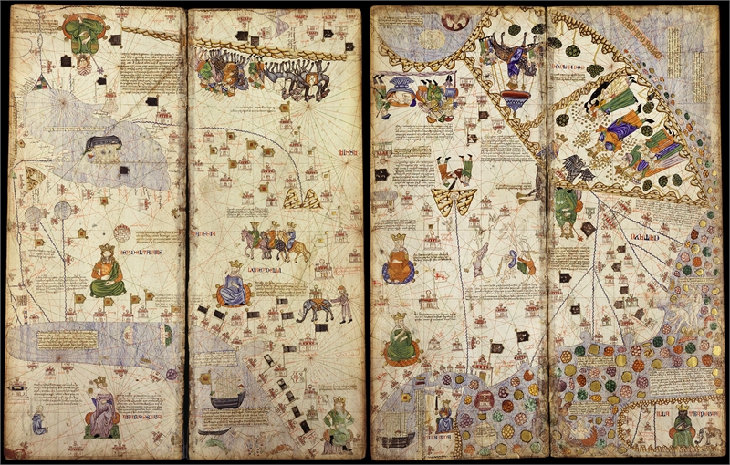

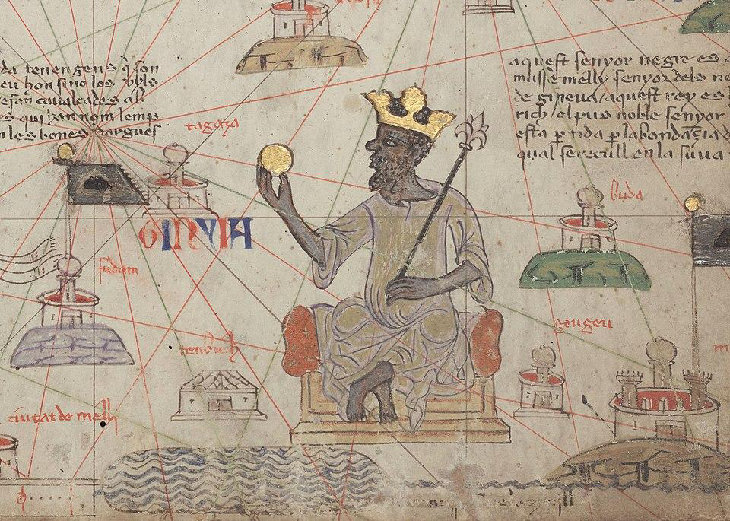

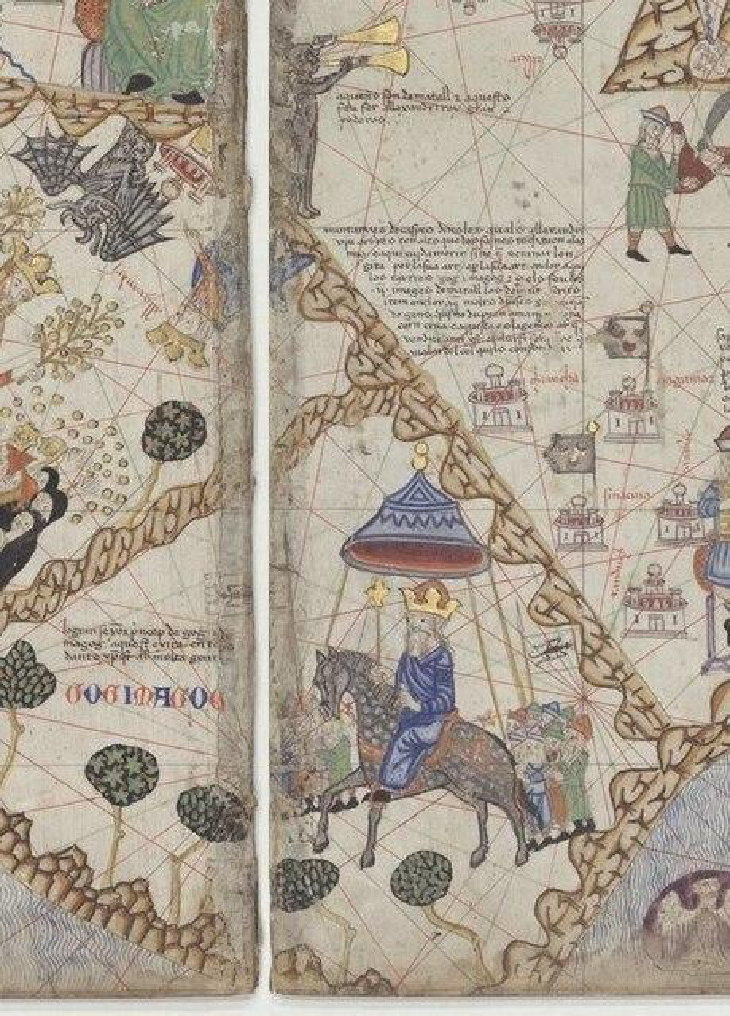

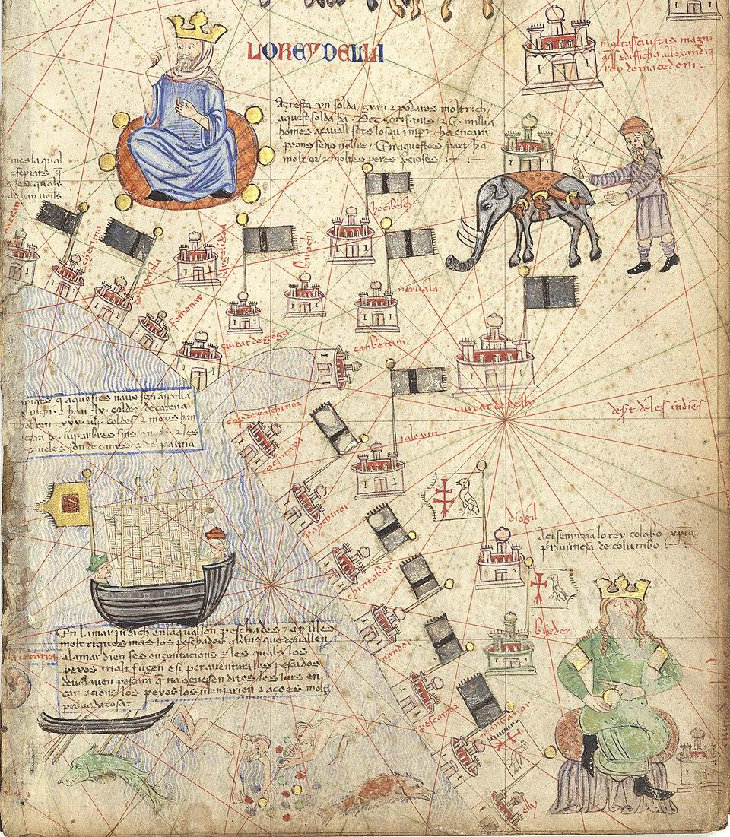

In West Africa, we find an image of Mansa Musa, the wealthy ruler of Mali, holding a golden orb in his outstretched hand. In Asia, the Mongol emperor oversees the trade routes Marco Polo had described. And, if we look carefully at the edge of the map, we find that Cresques concealed a powerful message for Jewish life in a hostile world.

The Jews of 14th-century Majorca were in a precarious position. Their property rights were limited, and they were required to wear identifying yellow badges. Yet, many became indispensable through learning, craftsmanship, and trade. Abraham Cresques and his son Yehudah—who would later be forced to convert—lived in a fragile space between respect and danger.

The Atlas brings this anxiety to life. Gog and Magog—the apocalyptic threat foretold in Jewish prophecies—lurk as hostile nations at the map's edge. As art historian Dr. Ariel Fein notes, “for Cresques, living in a period of increased persecution under Christian rulers, it highlighted a messianic hope for the lost tribes to cross the River Sambatyon and herald the coming of a Jewish messiah and an independent Jewish future.”1

At the same time, Cresques held out hope for his particular historical moment. We can see this in his surprising choice of illustrations. Though commissioned by a Christian king, Cresques included regal images of foreign rulers as well. Fein draws attention to just how unusually these rulers are portrayed: “not as foreign or menacing, but rather as respected, powerful, and prosperous political rivals.” Cresques illustrated a global society in which difference did not necessarily imply conflict; in which powerful civilizations could potentially coexist.

In Cresques's hands, the world as it is overlaps with the world as it could be. His map is both a navigational tool and a moral vision, acknowledging the perils that surround us while still insisting that history has direction and purpose. In an age like ours—algorithmically precise but often empty of meaning—Cresques reminds us that finding our way requires both spatial and spiritual orientation.

Cresques used his work to articulate a vision of balance that speaks directly to our time. In an age of exaggerated dichotomies—science vs. faith, national pride vs. global solidarity—his map suggests that the world is big enough to embrace them all.

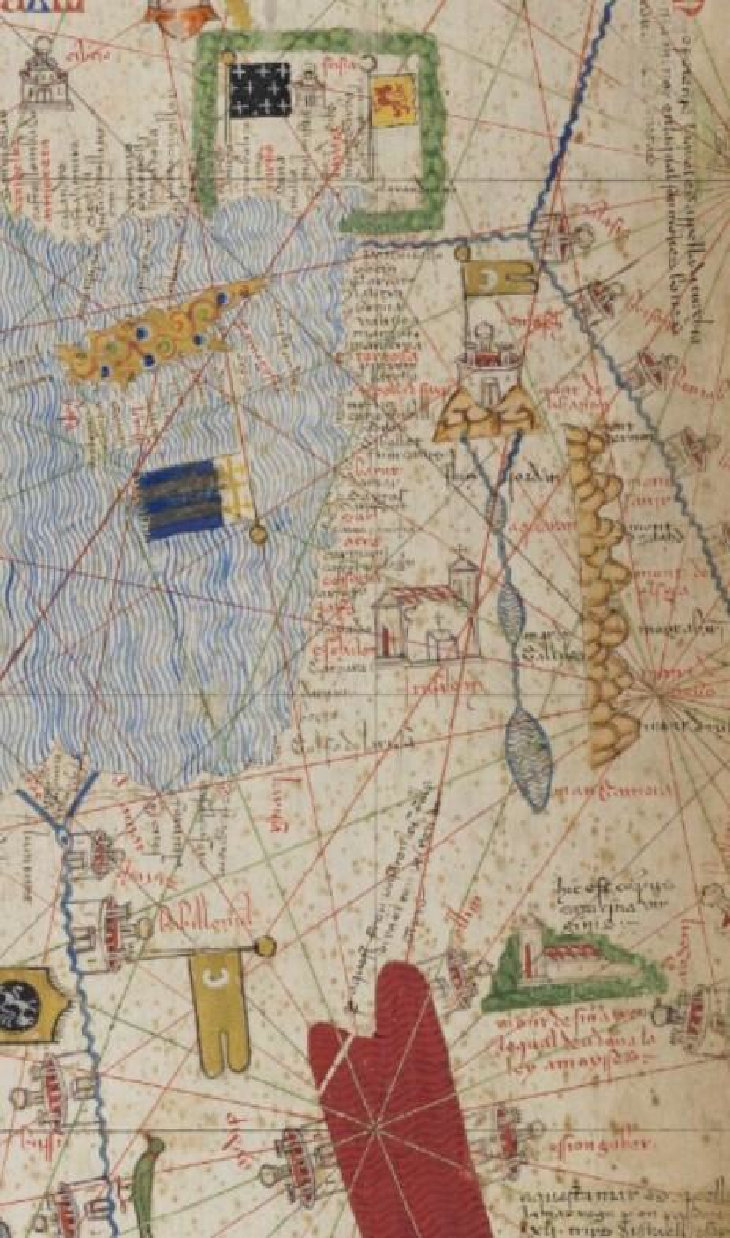

And like Cresques’s world, our lives also need a center. His map placed Jerusalem in the middle of everything—a symbolic heart that held the pieces together. Each of us has to decide what sits at the center of our own map. Is it faith, family, conscience, or something else?

The Land of Israel at the center of the map, with the biblical Red Sea painted in bright red. Cresques includes a note that this is where the children of Israel escaped from the Egyptians.2

We may not sail medieval seas, but we are still charting our place in a vast and complicated world. Cresques reminds me that the goal isn’t only to draw the world accurately, but to live within it wisely—to keep our values at the center while we endlessly explore new horizons.

Never heard of this before! Eye opening historical context