Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

7 min read

My grappling with God in the aftermath of my daughter’s sickness and subsequent passing at age 14.

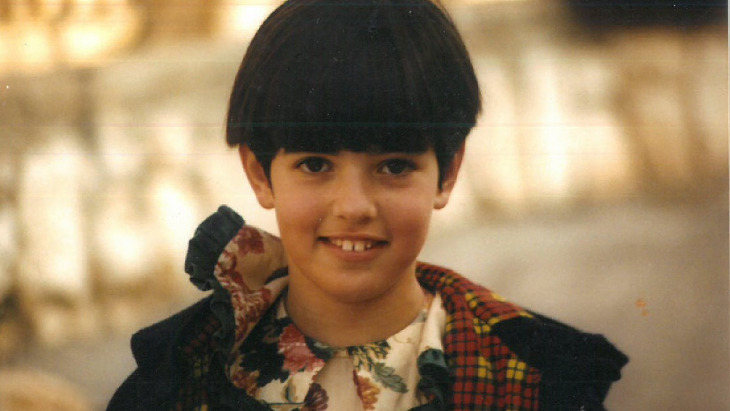

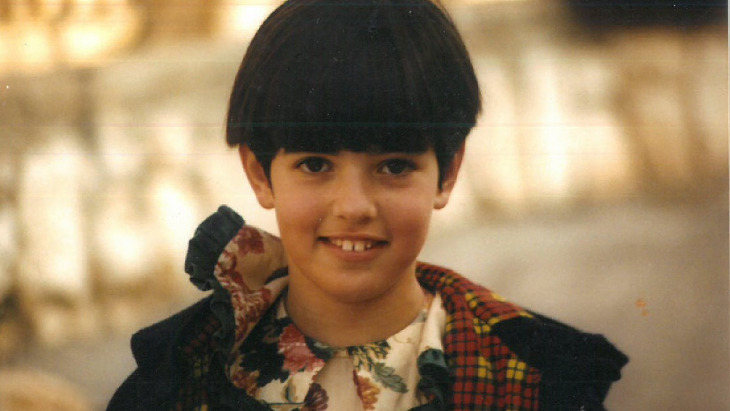

In January, 1990, we received the devastating news that our oldest daughter, Rivka, just over two years old at the time, had leukemia, a cancer of the blood system.

Within the first week of her diagnosis, we were given a very optimistic prognosis: 85–90 percent likelihood for a complete recovery.

Initially, everything seemed to go according to plan, as Rivka went into remission right away. Following 26 months of chemotherapy, mostly on an outpatient basis, we were very hopeful that as the years went on, our daughter’s leukemia would become a thing of the past. She remained in remission and off-treatment for seven additional years, during which time we returned to live in Israel.

Tragically, the nightmare that every parent of a cancer survivor fears occurred in May 1999. Her leukemia, which had somehow remained dormant and undetected for almost ten years, came back into our lives. Rivka was then 11 years old. The doctors told us this was less than 1 percent likely to happen.

Our daughter’s prognosis for a complete recovery was now significantly worse, and we were advised to attempt the risky procedure of a bone marrow transplant. This involves high doses of chemotherapy, along with intensive radiation over the entire body. While this completely obliterates the patient’s immune system, the hope was that it would also eliminate the leukemia in Rivka’s blood.

She received the bone marrow transplant from her baby brother, Yehudah, not quite two years old at the time, just before Rosh Hashanah, in September 1999. Rivka successfully accepted the transplant and was able to leave the hospital after three months, just a few weeks before her bat mitzvah. Ten months after receiving the bone marrow transplant, however, Rivka was struck with a second relapse. At that point, her odds of recovery, according to standard medicine, became dramatically lower.

The doctors attempted a number of different experimental approaches, involving a remarkable total of three additional bone marrow transplants, over the following two years. The first two of these transplants, which also came from her brother, lasted six months each before she relapsed yet again. The final one, which she received from an unrelated donor in England, only lasted a couple of months.

In the end, it was the complications from this last transplant that caused her to pass away, early Shabbos morning, June 29th, 2002.

Each year, on our daughter’s yahrzeit, I would share my research on related topics, as a merit for her, sharing my perspectives in various classes and on my website JewishClarity.com.

What have I learned all these years? Perhaps the most significant point concerns the great fundamental in life of free will. There is a common thought in today’s world that the ability to make choices, particularly within situations of hardship, is greatly limited. That, however, is not the Jewish perspective, and that was most certainly not my experience. While it was often very difficult to keep choosing during the many ordeals we went through, this was ultimately the difference between being empowered, and not merely seeing ourselves as helpless victims. The choices we faced were most significant in three different areas.

Every person has to deal with pain in their life, sometimes minor, sometimes serious, and sometimes overwhelming.

First of all, every person has to deal with pain in their life, sometimes minor, sometimes serious, and sometimes overwhelming. This pain is often a reality we are unable to control. How we relate to this pain, however, is where we are able to make choices. If we focus on the fact that there is a purpose to these painful situations, we will then have the ability to grow from them. If, on the other hand, we choose to ignore any possibility of there being a purpose, we will then be left with only suffering.

While the pain of the situation is a reality, suffering is a choice.

While no one likes pain, if there is enough of a purpose or benefit, we will often welcome a painful situation. An obvious example of this is childbirth. Women are willing to undergo the pain and difficulty of pregnancy and childbirth because having a child at the end of the process makes it all worthwhile. Our goal in life is, therefore, not the avoidance of all pain, but rather the avoidance of any pain that is lacking in purpose or meaning.

Secondly, one of the most difficult areas for the mourner to navigate involves one’s emotions. Emotions play a critical role in our lives and in our fulfillment of Judaism. The goal is to avoid the extremes and strive for a normal balanced approach. On the one hand, one who doesn’t mourn properly is considered to be cruel. But, at the same time, if the expression of the grief is excessive, this is not considered to be healthy. I discovered that we generally possess much more ability to control our emotions than we give ourselves credit for.

And finally, a fundamental decision that every mourner needs to make is how they will live their life in the long term. Judaism has a series of mandated time periods which begin from the moment that one’s close relative passes away. Once all of those times have finished, however, the mourner can ether begin to rejoin life and the world, or maintain his or her separation and isolation.

Recognizing ourselves as members of the Jewish nation and as part of Jewish history can help us to gradually transition back to a normal life. The Jewish people have been managing to do this for thousands of years, beginning with the destruction of the two different Temples, and through all of the terrible pogroms, persecutions, and antisemitism that we’ve had to deal with ever since. Throughout these many difficulties and challenges, Jews always continued to live their lives. They enjoyed celebrations, observed holidays, and remained connected to their communities. As impossible as it may seem to find the proper balance between the conflicting emotions that fill our lives, we have the model of the Jewish people throughout the generations showing us that it can and must be done.

It is striking that the Hebrew word nechama, meaning comfort or consolation, actually refers to reconsidering something or changing one’s perspective. The acceptance of nechama is, therefore, the willingness, within one’s heart, to view the situation differently, and to thereby be able to continue with one’s life.

While the tragic reality will remain exactly as it was, how we accept it and how we relate to it can definitely change. When someone close to us passes away, we also experience a type of death. Without the spiritual healing and the renewed wholeness that we get from Nechama, consolation, it would be impossible for us to continue to exist. The remarkable quality of nechama gives us the strength to reconsider not only the painful situations we are dealing with, but what we ourselves are capable of.

Rabbi Asher Resnick recently published his book, Pain is a Reality, Suffering is a Choice – Grappling with Divine Justice which is the outgrowth of over 30 years of personal engagement with loss and pain, and his drive to understand life’s challenges from a Jewish perspective.

Based on hundreds of classical Torah sources, the book is an extensive presentation of the Torah’s view and wisdom on dealing with difficulties in life, and is presented through the prism of the challenges his family has gone through as a result of his daughter’s illness and passing away at a young age.

Click here to order your copy of Pain is a Reality, Suffering is a Choice.