An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

4 min read

Why were European Jews who appeared in court subjugated to humiliating acts like standing bare-chested and bare-headed on a bloody pigskin?

In the year 532 CE, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian proclaimed that Jews could not provide testimony in a Christian court. The prevailing assumption was that the word of a Jew could not be trusted.

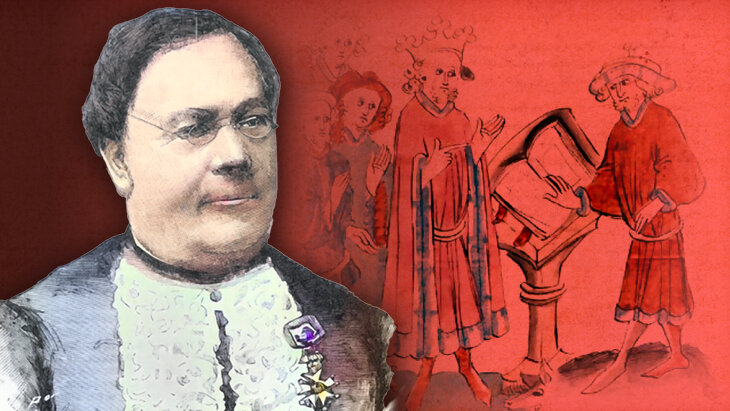

A 17th century depiction of a Jew taking the More Iudaico. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A 17th century depiction of a Jew taking the More Iudaico. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This proved to be a fairly unworkable ban, so over the centuries a bizarre ritual developed, designed to intimidate Jews from their presumed predilection for untruthfulness. Known as the More Iudaico, Latin for “Jewish custom,” Jews who appeared in court were required to subjugate themselves to a broad array of humiliating circumstances, from calling down Biblical curses upon themselves if they were to lie in court, to standing bare-chested and bare-headed on a bloody pigskin, with one hand on an open Bible, to discourage any possible dissimulation.

Amazingly, some version of the More Iudaico persisted well into the 19th century, even in otherwise “enlightened” countries like England and France.

That is, until 1838, when young Lazare Isidor appeared on the scene. A graduate of the Yeshivah of Metz, a town in eastern France that was once the home of the great Rabeinu Gershom Me’or ha-Golah (“Light of the Exile”) whose ban on polygamy shaped Ashkenazi for a millennium. In his very first posting in the town of Pfalzburg, barely 24 years of age, Rabbi Isidor came face to face with this medieval indignity when a congregant was ordered to take the More Iudaico as part of required court testimony. As per the local judicial procedure, the oath was to be administered in a synagogue.

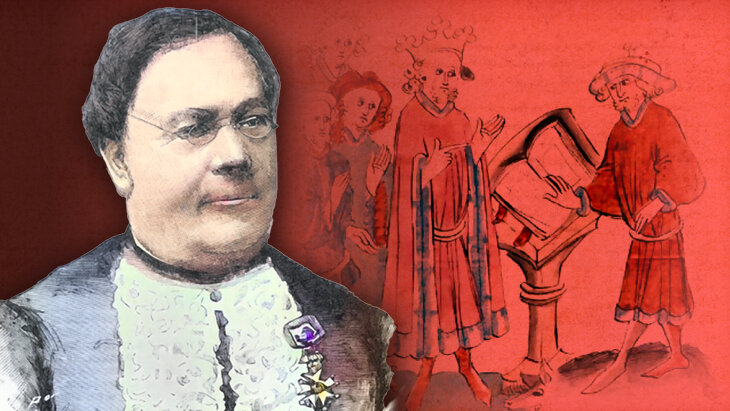

Rabbi Lazare Isidor (1806-1888) in later middle age. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Rabbi Lazare Isidor (1806-1888) in later middle age. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Rabbi Isidor refused to allow the sanctuary to be profaned by such an insult to the dignity of a fellow Jew (even if, as was the case under consideration, the Jew was willing to debase himself).

The demand was especially galling, given that the Jews of France had been formally emancipated in revolutionary France for almost half a century. Even though the long-standing and obvious discrimination against Jewish French citizens was such an egregious violation of the principles of “Equality, Freedom and Fraternity,” Rabbi Isidor’s opposition brought him a charge of contempt of court.

French Jewry galvanized themselves on his behalf and a young firebrand attorney named Adolphe Crémieux took up the case.

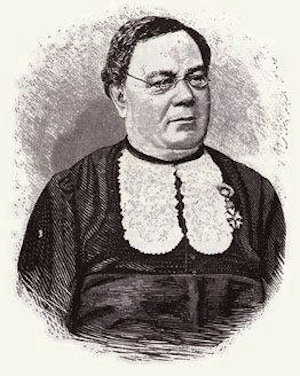

Adolphe Crémieux at the time of the Lazar trial. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Adolphe Crémieux at the time of the Lazar trial. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Crémieux, who would soon go on to great fame as a fearless advocate of Jewish rights in infamous cases like the Damascus Blood Libel of 1840, mounted a brilliant defense that shamed the French Republic for maintaining this vestige of medieval antisemitism. With ferocious and soaring oratory, Crémieux berated the court:

Do you believe that French Jews are unworthy of equality with French Christians? You say the Jews cannot understand the importance of taking an oath with an upraised hand. How many Christians fail to understand that concept? How many raise their hands and say, “I swear,” without realizing the sanctity of that holy gesture, that sacred word?

By what right, you judges, do you proclaim yourselves theologians? By what right, as Catholics, do you seek to regulate the conscience of a Jew; as Magistrates, to regulate the conscience of a Rabbi?

Rabbi Isidor was duly acquitted, and within fairly short order, the infamous More Iudaico was abolished.

Rabbi Isidor’s bold condemnation of the More Iudaico signaled a new direction for French Jewry, asserting their rights as full citizens of the Republic, entitled to equal treatment under the law. As Rabbi Isidor put it, “We have shown that we were worthy of liberty, worthy of the title of citizen, and that it was possible to be at once a Jew and a Frenchman.”

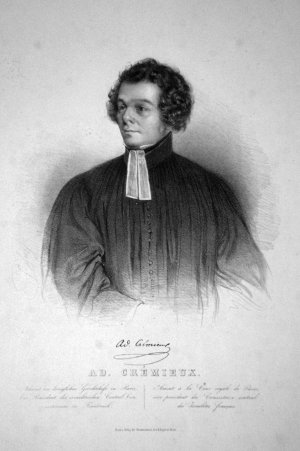

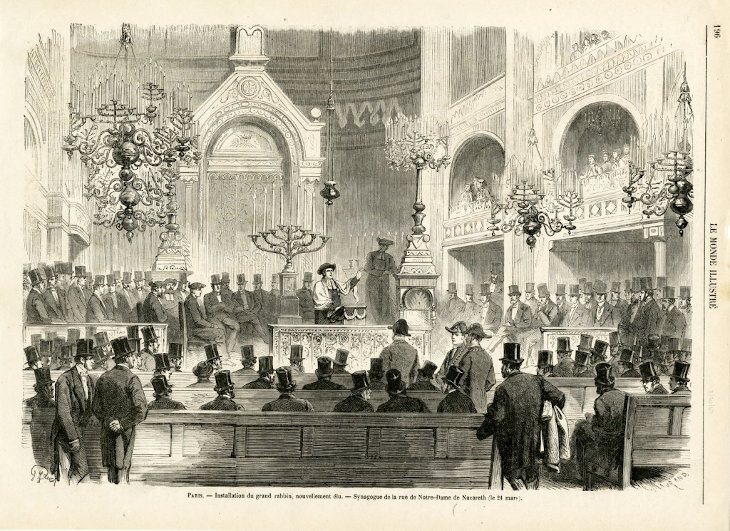

Installation of the newly elected Chief Rabbi Lazar Isidor from Le Monde Illustre. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Installation of the newly elected Chief Rabbi Lazar Isidor from Le Monde Illustre. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A noted scholar and popularizer of Torah study, he was named Chief Rabbi of Paris at age 33, but this would not mark the pinnacle of his career. For his courageous and consistent efforts on behalf of French Jewry, he was ultimately recognized with the highest ecclesiastical title in the land, becoming Chief Rabbi of France in 1867, a position he held until his passing in 1888.