Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

11 min read

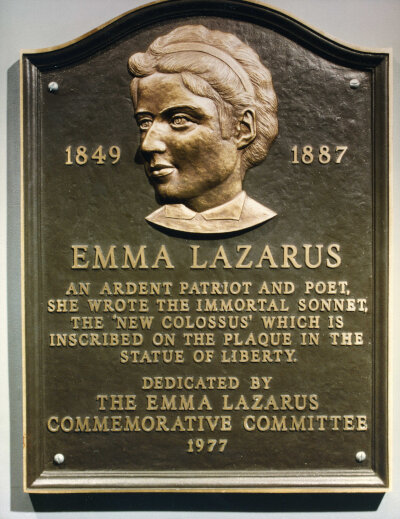

The famous Jewish writer should be remembered for more than her immortal words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty.

If Emma Lazarus is remembered at all, it’s for her immortal words inscribed upon the inner wall of the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” For millions of refugees, her sonnet evokes America’s image as a nation of kindness fundamentally different from all the other great powers of world history.

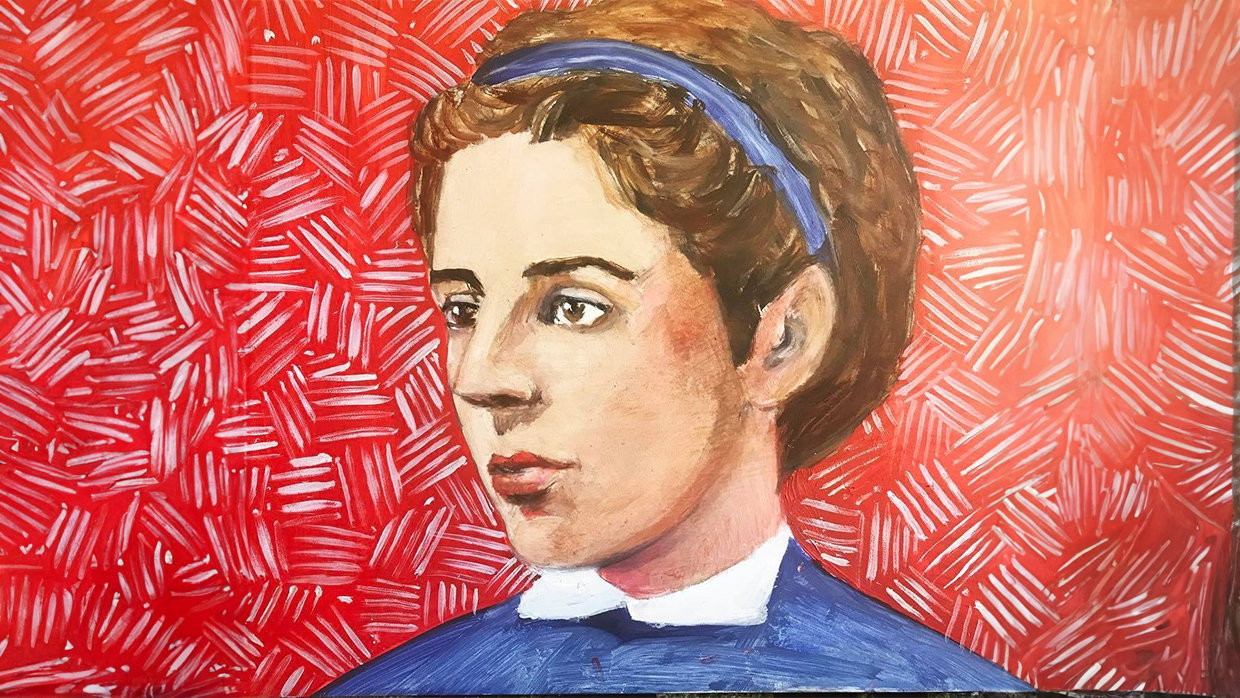

But who was this astonishing young poet who stunned the likes of the novelist Henry James, who wrote to his sister that he “met and fell in love with Emma Lazarus: a poetess, a magaziness, and a Jewess”? Who was this rising star of American literature, tragically cut down by illness at the age 38, just as she reached the height of her literary powers?

There is far more to Emma Lazarus than her remarkable poem. America’s first celebrity returnee to Judaism, she bravely stood up for her people and blazed a trail for thousands of Jews who would one day awaken to their roots.

Emma Lazarus was born in 1849 in New York City, where she would live the rest of her life. Both of her parents’ families arrived in Manhattan before the American Revolution, part of the small but influential Sephardic Jewish community in New York. Emma’s father, the successful sugar merchant Moses Lazarus, had little interest in Judaism or the Jewish community. A member of the exclusive – and very non-Jewish – Union and Knickerbocker Clubs, he bought a summer home in the fashionable section of Newport, Rhode Island, far from the town’s historic synagogue.

Emma grew up with little awareness or understanding of her heritage and successfully integrated into Christian society.

Unsurprisingly, Emma grew up with little awareness or understanding of her heritage. She observed Christmas with her Christian friends and spent Friday evenings at the elegant salons of Richard and Helena Gilder, the editor and illustrator of Century Magazine. At a time when most American Jews and Christians avoided social mingling, Emma successfully integrated into Christian society. Other than her many sisters, she had no close Jewish friends. All of her best friends were Christian.

Though she lacked a strong Jewish education, Emma recognized early on that she was different. In her early twenties, while strolling through Newport, Emma was drawn to the neglected Newport synagogue, where few Jews then prayed. Everywhere she looked, she found symbols of the Jewish people’s decline:

No signs of life are here: the very prayers

Inscribed around are in a language dead;

The light of the "perpetual lamp" is spent

That an undying radiance was to shed.

At this early stage, Emma calls Hebrew a “language dead” and considers the light of Judaism “spent.” But she does so with deep sadness, perhaps sensing that this abandoned synagogue reflected her own neglected religious identity.

What prayers were in this temple offered up,

Wrung from sad hearts that knew no joy on earth,

By these lone exiles of a thousand years,

From the fair sunrise land that gave them birth!

(In the Jewish Synagogue at Newport)

As Emma’s reputation grew in literary circles, she largely avoided Jewish themes, with one prominent exception: Christian antisemitism. In a highly publicized case in 1877, the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga, New York, refused to admit Joseph Seligman, a wealthy German Jewish banker. The owner, Judge Henry Hilton, explained that he had no objection to “true Hebrews,” the Sephardic Jews with a long history in America, and only objected to “greedy” and “dirty” immigrant Jews like Seligman. Emma never forgot this act of blatant and public antisemitism.

In an essay that could have easily been written today as Jewish students are squeezed out of elite universities and are harassed on campuses throughout America, she wrote: “Within recent years… in our schools and colleges, even in our scientific universities, Jewish scholars are frequently subjected to annoyance on account of their race… In other words, all the magnanimity, patience, charity, and humanity, which the Jews have manifested in return for centuries of persecution, have been thus far inadequate to eradicate the profound antipathy engendered by fanaticism and ready to break out in one or another shape at any moment of popular excitement.”1

Though she was personally spared from explicit discrimination, Emma was regularly referred to as “the Jewess” by her Christian friends. As she later wrote in a letter to Philip Cowen, “I am perfectly conscious that… contempt and hatred underlies the general tone of the community towards us.” Her personal experiences led her to study the long history of hypocritical Christian antisemitism, a theme she would return to in many of her poems, including The Death of Rashi and The Crowing of the Red Cock:

When the long roll of Christian guilt

Against his sires and kin is known,

The flood of tears, the life-blood spilt,

The agony of ages shown,

What oceans can the stain remove,

From Christian law and Christian love?

(The Crowing of the Red Cock)

Emma’s growing identification with her people accelerated in the wake of a terrible outbreak of Russian pogroms in the early 1880s. Russian antisemites murdered over 40 Jews, raped hundreds of Jewish women, and destroyed thousands of Jewish homes and businesses. Horrified and shaken by the news, Emma’s Jewish consciousness, always present if often subdued, took center stage. Overnight, it seemed to many critics, she was transformed into “a flaming prophetess whose lines reverberated across the continents.”2

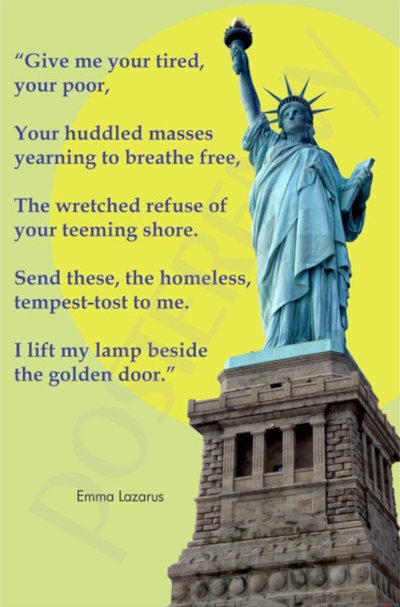

With stirring Jewish pride and righteous fury, Emma published a book of poetry, Songs of a Semite, in which she fully and unequivocally embraced her Jewish identity. With this slender book of powerful poems, Emma declared that she intended to stand up for “disgraced, despised, immortal Israel”3 without apology or hesitation. As an anonymous reviewer wrote, he had finally “come upon a Jewess who made a departure from the rule of silence.”4 Suffused with defiant Jewish pride, Emma’s Jewish poems should be required reading for every Jewish child.

Written 14 years before Theodor Herzl launched political Zionism with the publication of The Jewish State, Emma called upon her downtrodden people to rise up in strength and return their ancient homeland. Evoking Ezekiel’s powerful image of dry bones come to life, Emma wrote:

The Spirit is not dead, proclaim the word,

Where lay dead bones, a host of armed men stand!

I ope your graves, my people, saith the Lord,

And I shall place you living in your land.

(The New Ezekiel)

In her simple but powerful poem, The Banner of the Jew, Emma called for action. The Jews themselves must rise up, fight back and take their destiny in their own hands. Anticipating Herzl, she called for a modern Ezra to lead his people home:

Wake, Israel, wake! Recall to-day

The glorious Maccabean rage…

Oh deem not dead that martial fire,

Say not the mystic flame is spent!

With Moses' law and David's lyre,

Your ancient strength remains unbent.

Let but an Ezra rise anew,

To lift the BANNER OF THE JEW!

Not content with writing poetry, Emma founded the Society for the Improvement and Emigration of East European Jews in 1883, whose goal was to raise money to send large numbers of suffering East European Jews to resettle in the holy land. The Society corresponded and shared ideas with Baron Maurice de Hirsch and the Alliance Israelite Universelle. At the same time, Emma published a series of 15 essays in The American Hebrew, later published together as An Epistle to the Hebrews, in which she made her case for the return of the Jewish people to their ancient homeland.

Emma drew upon the writings of both Jewish and Christian proto-Zionists like George Eliot, Laurence Oliphant and Leo Pinsker, and used her literary celebrity to popularize them in America. “A home for the homeless, a goal for the wanderer, an asylum for the persecuted, a nation for the denationalized. Such is the need of our generation, and whether it be voiced in the hissing denunciations of Anti-Semitism, in the enthusiasm of helpful Christian advocates, or in the piteous appeal from Hungary and Galicia, from Bessarabia and Warsaw, the call is too distinct for misconstruction, and too loud to remain ignored and unanswered.”5

Her call to return home met with stiff opposition. Only two years later, in 1885, the Union of Reform Congregations issued its infamous Pittsburgh Platform, stating, “We consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community. [We] expect therefore neither a return to Palestine nor a restoration of… the Jewish state.” Meanwhile, Abram S. Isaacs, later the editor of The American Hebrew, rebuked Emma, arguing that it was “unwise to advocate a separate nationality… at a time when anti-Semites are creating the impression that Jews… are only Palestinians, Semites [and] Orientals.”6

Despite her passion and prominence, Emma’s Society fell apart within two years. In the words of Bette Roth Young, “she was the wrong age, the wrong sex, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.”7 Emma herself sensed early on that she was ahead of her time. Writing 65 years before the establishment of the modern State of Israel, she presciently wrote: “In all such questions as this, that which is agitated to-day, is formulated and acted upon on the morrow, or as Emerson put it, ‘the aspiration of this century is the code of the next.’”8

Five months after the disbanding of her society, Emma sailed to Europe with her sisters. By January 1887, she was seriously ill with cancer, and her sisters brought her home that July. She died on November 19, 1887, only 38 years old.

From the moment of Emma’s untimely death, many of Emma’s family members and friends sought to minimize her Jewish identity. Annie Lazarus Johnston, Emma’s sister who converted to Anglican-Catholicism, denied a publisher’s request to publish Emma’s Jewish poems. She wrote: “There has been a tendency on the part of the public to over emphasize the Hebraic strain of her work, giving it this quality of sectarian propaganda, which I greatly deplore, for I consider this to have been merely a phase in my sister’s development, called forth by righteous indignation at the tragic happenings of those days. Then, unfortunately, owing to her untimely death, this was destined to be her final word.”9

Annie and much of the family found Emma’s embrace of her “backwards” people both baffling and embarrassing. What could possibly compel her to lean into her identity as a Jew, one they had fled from their entire life?

In a profound way, Emma was a fiercely dedicated Jew.

The entire arc of Emma’s life refutes this claim. As a young woman, she referred to Jews as “they”; but as she matured, she referred to them as “we.” The title of her greatest work, Songs of a Semite, was a public proclamation of Emma’s wholehearted identification with her people. As she herself made clear, “I do not hesitate to say that our national defect is that we are not ‘tribal’ enough; we have not sufficient solidarity to perceive that when the life and property of a Jew in the uttermost provinces of the Caucuses are attacked, the dignity of a Jew in free America is humiliated… Until we are all free, we are none of us free.”10

Though she did not live an observant Jewish lifestyle – perhaps she would have had she lived – Emma Lazarus was, in a profound way, a fiercely dedicated Jew. Defying the expectations of her family and social circle, she boldly asserted her solidarity with her people, a people she hardly knew but deeply loved. Her willingness to stand up for her beleaguered nation, to fight on their behalf, elevated her from a talented writer to the voice of her people.

For Jews who were not raised in religious homes or did not receive a proper Jewish education, Emma is an inspiration. “No words of praise can be too great for one who… voluntarily returns to the old household, publicly proclaiming herself one it its members, and bringing to it not alone a heart filled with sympathy, but the pen of a prophet…”11

May her memory lift the “banner of the Jew.”

Love it thank you so much I had no idea what she was about. Very interesting and inspiring.

A most enlightening article. I never knew anything about her. That brings to mind the fact that the world of Jew hatred has always minimized Jewish achievement and contribution. I believe it's because they are envious of our accomplishments and are contemptuous of our G-d given morality and religious beliefs and practice. But consider this: If it was not for the Torah and the Jews, the world would be peopled with nothing but pagans and primitives with their degrading and despicable practices. Even Christianity would not exist. Imagine that!

Shalom. Well written and a very nice introduction on the works and times of Emma Lazarus. Thank you

Wonderful! Emotionally moving to me! My first doctoral advisor--Ben Halpern--mentioned Emma's impact on early Zionist history, but I never followed up in considering that role. My loss; this article, my gain.

A TRULY REMARKABLE HUMAN BEING,THAT MOST PEOPLE,ESPECIALLY THE TEENS,KNOW NOTHING ABOUT!THE SCHOOLS SHOULD BE ACTIVE IN PUBLISIZING HER CONTRIBUTION TO JUDAISM AND ISRAEL!!!

Emma Lazarus is an inspiration to all the Jewish People. Thank you for publicising her life, especially through her poetry.

A real eye opener. I now think of. Emma Lazarus, not only as a talented poetiss, but a heroic Jew in a land where so many of her brethren were so anxious to deny their faith, their people and their destiny.