Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

11 min read

Sarra Copia Sullam was a famous Jewish writer at a time women and Jews were marginalized.

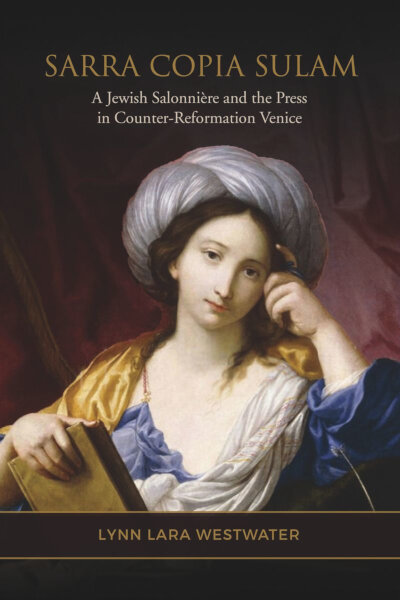

A new novella is bringing attention to a fascinating Jewish woman of the Renaissance era. Sarra Copia: A Locked-In Life by Nancy Ludmerer (WTAW Press: 2023) tells a fictionalized version of the life of Sarra Copia Sullam, a Jewish woman who ran a literary salon in her home in Venice’s Jewish Ghetto in the 1600s. Educated men – both Christian and Jewish, including religious leaders – frequented Sarra’s home, listening to this brilliant Jewish woman expound on the great ideas of the day.

“I want the Sarra Copia in the book to come alive for readers,” explains Ludmerer, in a recent conversation with Aish.com. Here are a few facts about Sarra Copia’s remarkable life.

The word “ghetto” originated in Venice. In the Middle Ages, over a dozen bronze foundries were located on a small island in the city. The work required fires and was so dangerous in an urban setting that the metalworks were forced to relocate outside the city. The land where the foundries once stood was damp and undesirable and stood empty for years. In 1516 the Venice city governors voted to relocate all Jews in the city to the cramped island of Ghetto, offering them security, in return for their freedom.

Thousands of Jews lived in the Ghetto. During the day, Jews were allowed to do business throughout Venice, but at sundown they had to return where they were locked in for the night. Metal gates barred passage across the island’s only link to the the rest of Venice. The Jewish community was forced to pay guards to man the gates. The only exception were Jewish doctors, who were allowed to leave the Ghetto after dark if they were summoned to treat a gentile patient.

Venice’s Jews faced many other restrictions, as well. They were forced to wear yellow hats and other garments, and could practice only a small handful of professions. For many years, it was illegal to study the Talmud in Venice. Yet Venice’s Jewish Ghetto offered European Jews relative freedom compared to many other locales. Jews moved to Venice from throughout Italy, as well as Spain, Portugal, Germany and elsewhere. The Ghetto hummed with activity and intellectual debate. Five synagogues bustled with prayer and study every day. By 1650, approximately 4,000 Jews lived in the Ghetto, and nearly a third of all the Hebrew language books published in Europe were published in Venice.

Sarra Coppia Sullam was born into this heady environment in the year 1592. Her father, Simone, was a successful Sephardi trader who died when Sarra was fourteen years old. Reading about Sarra and her family on a visit to the Jewish cemetery in Venice is what first spurred Nancy Ludmerer to write a novella based on Sarra’s life. She is buried next to her father, “who encouraged her gifts,” Ludmerer explains. “I was so struck by his will: he had so much respect for his wife and daughters. He specified that his daughters were free to marry whomever they pleased. His wife was the executor of his will. In addition to taking care of his family, he specified an annual donation to poor Jews in the holy land.”

Little is known about Sarra’s personal life. She married very young. Her husband, Jacob Sullam, was a banker and a prominent leader of the Venetian Jewish community. Sarra had a daughter who died before her first birthday. After a subsequent miscarriage, Sarra and Jacob were never able to have more children.

Jewish Ghetto in Venice

Jewish Ghetto in Venice

It’s likely that as wealthy, prominent people, Sarra and Jacob had a relatively spacious room in one of the buildings ringing the two courtyards of the Jewish Ghetto. Yet even for those comfortably off, the Ghetto was terribly overcrowded. Unable to build outside the confines of the Ghetto, Venetian Jews built up, adding story upon story to existing buildings. The Venetian Ghetto has the world’s earliest “skyscrapers”: seven and eight story apartment buildings built at a time when such heights were unheard of for residential buildings. With thousands of people confined to such a small area, the buildings were cramped. More than one large family often lived together in a single room.

At night, when the Ghetto gates swung shut and were locked by the island’s guards, Sarra and Jacob – like all their friends and relatives – were unable to leave, forced to pace the cramped courtyards with thousands of other Jews if they wished to leave their small, dark living quarters and get some fresh air.

Rabbi Leon of Modena. (Apparently the Jews of Italy didn’t adopt the custom of wearing a head covering.)

Rabbi Leon of Modena. (Apparently the Jews of Italy didn’t adopt the custom of wearing a head covering.)

A sense of the rich intellectual world that Sarra inhabited can be gained by taking a look at the work of Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh de Modena (also known as Rabbi Leon Modena) (1571-1648). The Sullams and the Modenas socialized together, and Sarra was a congregant and a disciple of Rabbi Modena. Biographer Rabbi Hersh Goldwurm notes that Rabbi Modena “had an astoundingly versatile mind, and became expert in such diverse subjects as music, mathematics, philosophy, science, etc. He spoke and wrote Italian and Latin fluently, wrote good poetry, and was an expert orator. Above all, he was a master of Jewish learning, and was considered to be one of the foremost (rabbinic leaders) in Italy” (quoted in The Early Acharonim, Artscroll: 1989). Like Rabbi Modena, it seems that Sarra also enjoyed a rich and varied intellectual life.

Literary salons were fashionable across Europe during Sarra Copia’s life. These were formal gatherings at a specified time each week or month, where people would gather to share poetry, listen to lectures, and debate great themes of the day. The most famous literary salon in Venice took place while wearing masks, affording participants the chance to remain anonymous while they shared controversial opinions. A handful of salons in Venice had been led by Christian women through the decades: Isotta Nogarola (1418-1466), Cassandra Fedele (1465-1558), Vittoria Colonna (1490-1547) and others led successful salons. But doing so could be dangerous for women; one biographer notes that “while these women earned recognition for their literary skill, male associates often responded to them with slander, sexual interest, or indifference” (quoted in Sarra Coppia Sulam: A Jewish Salonniere and the Press in Counter-Reformation Venice by Lynn Lara Westwater, Toronto Italian Studies: 2019).

In 1618, when she was about 27 years old, Sarra Copia took the unusual step of opening her own monthly literary salon inside the Jewish Ghetto. It was an instant success, with prominent intellectuals gathering in Sarra’s home to hear her speak, to exchange ideas, listen to poetry, and play games. Prof. Howard Adelman of Queens University in Ontario describes the scene: “There was a stream of distinguished visitors – from Treviso, Padua, Vicenza, and beyond (who) congregated because she was a brilliant conversationalist…” Her salon was so impressive that the priest Angelico Aprosio, who was a member of Venice’s most prestigious literary salons, called Sarra’s gathers an accademia, an academy.

Ludmerer vividly imagines what Sarra’s salons might have been like: “We read and discuss works-in-progress, philosophy, religion. Sometimes we play music or sing. I decide the order of events - a delicate matter - and when appropriate, express my opinions…Often, I am the only Jew; invariably the only woman. On religious matters, I am outnumbered and outmanned. Nonetheless, I hold my ground.” (quoted from Sarra Copia: A Locked-In Life by Nancy Ludmerer, WTAW Press: 2023).

Ansaldo Ceba (1565-1623) was a poet who lived in a monastery in the Italian city of Genoa. He and Sarra never met, but they carried out a public literary discourse with one another – until, it seems, Ceba fell in love with Sarra.

Around the time that Sarra opened her salon, she began reading Ceba's poems. One was a long epic called Queen Esther about the Biblical Jewish heroine, which Sarra praised highly. She wrote to Ceba, saying she enjoyed his poem so much, she slept with it underneath her pillow. Ceba began to entertain the idea that somehow he and Sarra could be together. Sarra’s maiden name was Coppia and she used it in her writing. Coppia means couple in Italian, and Ceba wrote her a long letter musing on how appropriate her maiden name was, describing how the two pp’s in the middle of her name were like two Christians who were married to one another. Even though he was a monk and Sarra was married (and Jewish!), Ceba wrote that he hoped he could convert her and that they could live together happily as a Christian couple like those two p’s.

Sarra continued her public correspondence with Ceba – it boosted both of their literary profiles – but she immediately changed the spelling in her maiden name, removing a p and henceforth going by the name Copia.

Sarra soon got into more serious trouble with another Catholic cleric, Baldassare Bonifaccio (1585-1659), the Archdeacon of the town of Treviso, who spent much of his time in Venice.. Bonifaccio attended Sarra’s salon which put her life in peril.

At one of Sarra’s literary salons, participants discussed the immortality of the soul. Afterwards, Bonifaccio wrote a long Discorso (discourse) on the immortality of souls and accused Sarra of not believing in this core Christian and Jewish tenet. He suggested that she convert to Christianity and thus resolve her supposed blasphemy. This was a grave charge in 17th century Italy, and Sarra was terrified that Bonifaccio’s baseless accusation could harm the entire Jewish community. Bonifaccio’s slanders gave the Roman Inquisition an excuse to try Sarra and perhaps even other Jews in Venice. None of the people who frequented Sarra’s salon came to her defense.

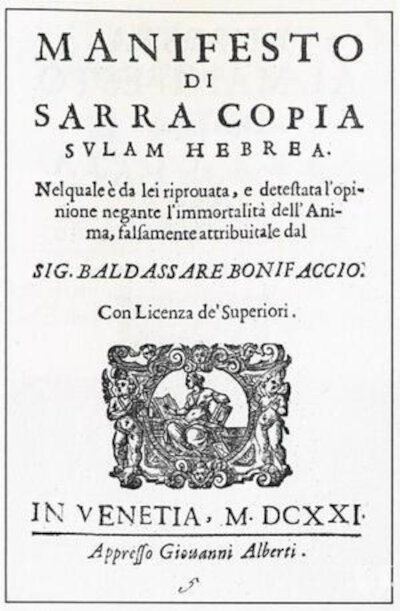

Sarra took to her room and spent two days penning a response. The result was magnificent: her Manifesto drew on Jewish and secular writings to marshal arguments for belief in the immortality of the soul. Sarra railed against Bonifaccio’s betrayal in accusing her of heresy, and dissected his arguments one by one. Sarra poured her entire being into this Manifesto; she even included four of her sonnets as she built her case, defending her Jewish beliefs, and expressing her hurt that Bonifaccio had endangered her and the entire Jewish community. The work “is a religious apology designed to protect her own community,” notes Westwater.

The Manifesto was an instant success. (It’s full name in English was The Manifesto of Sarra Copia Sulam, a Jewish Woman, In Which She Refutes and Disavows the Opinion Denying Immortality of the Soul, Falsely Attributed to Her by Mr. Baldassare Bonifacio.) Readers throughout Venice and beyond bought all the copies that Sarra printed and read and debated her points in many other literary salons. Her Manifesto was re-issued several times, as printers tried to keep up with demand for Sarra’s work.

Bonifaccio accused Sarra of not being the Manifesto’s author, claiming that Rabbi Modena must have written it. Bonifaccio never responded to Sarra’s criticisms, merely maintaining in his public correspondence that she ought to convert to Christianity.

Sarra’s salon continued for only a few years, until 1624. During that time, she was able to converse with educated, fascinating people from throughout Venice who all made the trek to the Jewish Ghetto. Sarra’s many poems continued to be well received and often read. Yet as a public figure, Sarra was slandered by some of the Christian men who attended her salon. She was accused of sexual impropriety and plagiarism. Her servants were induced to spy on her. Sarra spent years watching as her name was dragged through the mud by writers who concocted the most outrageous and damaging stories about her supposedly outlandish love life.

It’s unclear how deeply Sarra regretted opening her home to others who would later turn on her so viciously. Sarra lived to the age of approximately 49. She never stopped writing, and she and Jacob never left Venice’s Jewish Ghetto. For her entire life, she was surrounded by a close-knit, pious community, locked in at night, and was part of a highly religious, traditional society where life revolved around the synagogue, family, and Jewish holidays.

Her legacy to us are her beautiful literary works, some of which survive today.

Read about more remarkable Jewish women in Portraits of Valor: Heroic Jewish Women You Should Know by Yvette Alt Miller.

Thank you for the superbly interesting article about this brilliant, fascinating and principled woman.. a woman of valor, indeed!

Thanks for this most interesting article!

Fascinating!

Interesting to see another book on Sarra Coppio Sullam. She is one of the main characters in my Venice Beauties series of historical suspense, with THE GALLERY OF BEAUTIES (Level Best Books/Historia/2022) introducing her and her salon where she performs a play in her salon, written by Rabbi Leon di Modena.

Excellent article! I enjoyed learning about the Jewish Getto, especially. I also liked re-reading the parts of Nancy Ludmerer's book on Sarra Copia.