Why the Tenth of Tevet Feels Uncomfortably Current

Why the Tenth of Tevet Feels Uncomfortably Current

11 min read

Museums around the world erroneously label ancient Jewish artifacts “Palestinian.” That has to change.

In the year 66 CE, one of the greatest uprisings against the Roman Empire began in the kingdom of Judea in modern-day Israel. The “Jewish Revolt,” as it became known, pitted groups of Jewish subjects against their brutal Roman overlords.

Judea, the ancient Jewish homeland, became part of the Roman Empire in the year 6 CE. Now Jewish subjects were fed up with Rome’s brutal rule and fought back, driving Roman soldiers out of Judea’s capital Jerusalem. In celebration of what they hoped would mark a return to independent Jewish control of their homeland, the rebels issued new shekel coins. One coin, today held in the British Museum in London, was minted in 69 or 70 CE and says Shekel Yisrael (“Israel Shekel”) Year 4 (of the rebellion). The coin’s back bears the Hebrew words “Yerushalayim Hakadosh” (“Jerusalem the Holy”).

It’s a remarkable artifact from one of the most consequential moments in Jewish history. Yet visitors to the British Museum labels this coin, and countless other Judean objects, as “Greek coin from Palestine,” erasing its Jewish history.

The names for the land that encompasses today’s State of Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza (not to mention today’s nations of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and elsewhere) can be confusing. Here’s a crash course in six points:

1. Israel. The term is first found in the Torah, when a mysterious stranger, considered an angel in Jewish tradition, tells the Biblical patriarch Jacob: “No longer will it be said that your name is Jacob, but Israel, for you have struggled with the Divine and with man and have overcome” (Genesis 32:28). The name Israel comes from the Hebrew words for struggling with God. At that early time, the Torah described the land of present-day Israel as Canaan, named after an ancient non-Jewish tribe in the area named the Canaanites. Jews lived among them.

2. Kingdom of Israel. After the Jews were enslaved then freed from Israel, they returned to the land of Canaan and slowly began building a Jewish kingdom there. Nearly three thousand years ago, King David expanded a roughly 200-year-old independent Jewish kingdom to include Jerusalem as its capital. This is generally considered the beginning of the ancient Jewish Kingdom of Israel. His son King Solomon built the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, establishing Jerusalem as both the spiritual as well as political center of Jewish life.

3. Kingdom of Judah. After Solomon’s death, the kingdom split into two separate Jewish nations led by different kings: the Kingdom of Israel occupied the north, and the Kingdom of Judah, encompassing Jerusalem, in the south. The Kingdom of Israel came to an end when it was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 80th Century BCE.

4. Judea. Judah remained a Jewish kingdom, weathering exile and proxy rule by foreign empires including the Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans, who referred to it as Judea.

5. Syria Palaestina. In 135 CE, after yet another Jewish uprising, the Roman Emperor Hadrian ordered the name of Judea obliterated. He chose the name Syria Palaestina in reference to the ancient people Plishtim tribe, an ancient Greek seafaring group of pillagers who settled in the area of modern-day Gaza 3,000 and were the sworn enemies of the Jewish people, as a sign that Jewish rule in Judea was finally over. Though later Christian rulers preferred to call the land of the present-day Israel the “Holy Land,” the (anglicized) name Palestine remained current thanks to the many Latin scholars who referred to the area by its post 135 CE Roman name.

6. State of Israel. After the Allies defeated the Ottoman Empire in World War I, they renamed the area that comprises present-day Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Jordan. Present-day Israel, Jordan, and the West Bank was turned over to British rule under the name Trans-Jordanian Palestine. In 1948, following a UN vote on the matter, the modern State of Israel was established in much of the ancient Land of Israel. An Arab nation of Palestine was meant to be set up at the same time, but local Arabs rejected it. Instead Jordan and Egypt took over the land designated by the UN to become an independent Palestinian Arab state. Today, the West Bank is ruled by the corrupt Palestinian Authority and Gaza is run by Hamas.

This history is hardly a secret. Yet museums around the world refuse to identify Jewish artifacts from the ancient Kingdoms of Israel and Judah as such, routinely - and anachronistically - referring to them as Palestinian instead. Of all the many names for modern-day Israel, it’s curious that only one - Palestine - is used over and over again.

When the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures in Chicago went to label the 3,500-year-old Bronze Age jug in their collection, they correctly noted that it was found in the massive archeological site at Megiddo in northern Israel. It predates the Kingdom of Israel, predates the Kingdom of Judah, and predates the establishment of Palestine by nearly 2,000 years. Yet “Made in Palestine” is how this august museum classifies the find. Other ancient finds are similarly mislabeled.

The renowned Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto, labels items from ancient Judea as Palestinian. Take a look at this oil lamp from the 2nd to 1st Century BCE, found in the present-day State of Israel labeled as originating in “Syro-Palestine.”

In Brisbane, Australia, the Queensland Museum similarly labels items from Israel and Judea as “Palestinian.” To take one example, a 3,000-year-old pottery fragment is labeled as Palestinian, despite predating the naming of Palestine by millennia.

The Vatican Museums also mislabel ancient items as Palestinian. Take a look at this remarkable lamp with Greek writing on it that was found in Jerusalem.

Despite Jerusalem being the capital of the Kingdom of Judah at the time the lamp was likely made, the Vatican asserts this find is from “Syria-Palestine,” a political designation that wouldn’t exist for hundreds of years.

The Louvre is no different. Take this 7,000-year-old sickle. It dates from thousands of years before Israel, Judah, and Palestine ever existed, and was found in 1958 in the Israeli city of Beersheba, yet is named as belonging to Palestine and Transjordan.

The British Museum also labels even extremely old items, clearly dating from the Judean Kingdom period, as Palestinian. This 7th century BCE funeral inscription features Hebrew writing identifying the person buried underneath it as “Shebna” – yet is labeled a Palestinian artifact.

This Hebrew language seal reads “belonging to Hananyahu son of Gedaliah” and is labelled Palestinian, a term that wouldn’t come into use for nearly a thousand years after its creation.

The simple explanation for museums’ persistence in labeling items from ancient Israel, Judah, and before as Palestinian is ease of use. Chicago’s Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures explains as much, asserting that “The name Palestine, derived from the ancient Philistines, refers to the geographical area that comprises most of what is now Israel and Jordan.” Calling all artifacts found anywhere in Israel “Palestinian” might just be the easiest way to characterize them.

Yet this de facto policy is harmful. It creates the false narrative that there was a consistent political entity called Palestine that always existed, and that this Palestinian identity is the original, default identity in the Middle East. Labeling everything from the Land of Israel as Palestinian is ahistorical, and it gives the false impression that Jews outsiders and illegitimate. These dangerous assumptions are spreading.

A recent plaque in the British Museum accompanying an exhibit about the 3,000-year-old Phoenicians wrongly declared: “By the beginning of the first millennium BC the Israelites occupied most of Palestine.” The museum’s language was factually incorrect; there was no “Palestine” and the presence of two Jewish kingdoms in the ancient Middle East did not constitute an “occupation.” Yet this wrong-headed language echoes current political smears against Israel and Jews as having no place in contemporary Israel. The Museum’s persistence in labeling all Israeli artifacts as Palestinian reinforces this lazy and dangerous narrative, fostering the impression among visitors that Jews have no historical or contemporary connection to the Land of Israel.

The smear that ancient Jews had no place in a Palestine that never existed is spreading. The UN’s website asserts that “In early times, Palestine was inhabited by Semitic peoples…” and that “the tribes of Israel came to Palestine after their captivity in Egypt.” Again, Jews are depicted as outsiders with no business in ancient “Palestine,” a place that never existed.

Palestinian Authority officials for years have been encouraging museums and other cultural institutions to adopt the incorrect narrative that there was an ancient “Palestine” millennia before Emperor Hadrian named the Land of Israel Palestine and that it is present-day Arabs in the West Bank and Gaza - not Jews - who are heirs to all the historical artifacts found inside "ancient Palestine.”

“The Palestinian people are a direct continuation of the original inhabitants from the Stone Age to the present,” Palestinian Authority Director of Culture and Antiquities Kdeclared in 2024. “Therefore the Palestinian people own the land and history, and all the antiquities (found there) are the property of the Palestinian people. The Palestinian people is the legitimate her, and everything the occupation (that is, Israel) says is untrue…. Everyone knows that the Zionist claims are no longer historically acceptable.”

UNESCO, the UN’s Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization, has designated major sites such as the birthplace of Jesus, the Tomb of the Patriarchs, and the ancient Jewish fortress of Betar as “Palestinian” sites; none of the descriptions of the historical importance of these ancient Jewish artifacts contains even one mention of the word “Jew.”

Not all museums routinely default to labeling items found in the Land of Israel as Palestinian. The Egypt Museum in Cairo, for instance, is one of the world’s great collections of ancient artifacts and they carefully label items, resisting the trend to default to calling artifacts from present-day Israel as Palestinian.

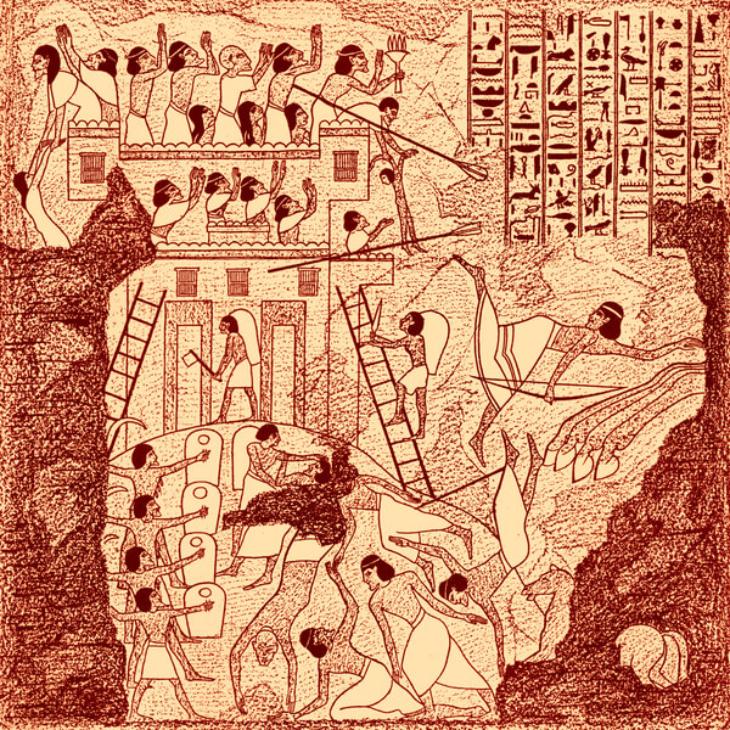

For example, consider this scene from Ramesses II’s palace in Karnak. It depicts the 1280 BCE attack by Egyptian forces on the Israeli city of Ashkelon. The museum correctly identifies Ashkelon not as a Palestinian city, but Israeli.

Israeli museums, unsurprisingly, are generally more careful to label items correctly, designating artifacts from ancient Judea as such, as well as from other ancient communities in the Middle East. For instance, one incredible holding in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem is a piece of graffito taken from a wall in the house of an ancient Cohen who served in the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem; the sketch depicts a Menorah and other instruments used in service in the Temple. The Israel Museum simply describes its provenance as from the Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem. The Israel Museum is careful to use the appropriate designation: for instance, in describing another one of its holdings, a late 19th century photograph of a Christian chapel on Mt. Carmel, it describes the artifact as being from Palestine, which the area was called when it was created.

There is some precedent for American museums ditching their reflexive, ahistorical use of the term Palestine. In 1986, for instance, the Metropolitan Museum of New York held a joint exhibit with the Israel Museum of treasures from ancient Judah and other periods of Middle Eastern history. Instead of labeling everything Palestine, the Met used the more neutral term “Holy Land” to describe the region. It’s a model for what other museums might do.

The use of Palestine as a catch-all term describing any and all artifacts from present-day Israel is well established. There are ways we can encourage museums in our communities to evolve.

Let’s make our voices heard, demanding accountability and change.