Holocaust Education Should Start in Elementary School

Holocaust Education Should Start in Elementary School

4 min read

4 min read

6 min read

Teaching the Holocaust in elementary school builds empathy, critical thinking, and early resistance to antisemitism, before prejudices harden and misinformation takes hold.

Holocaust education needs to start being taught in upper elementary school, as part of a multi-faceted response to rising antisemitism. Kids are sponges, and teaching this topic at a younger age will help people recognize the signs of antisemitism.

But that’s only the beginning of what age-appropriate Holocaust lessons can offer. The abundant documentation of the Holocaust can also open kids’ eyes to so many different things, including the importance of critical thinking, the way humans repeat certain behaviors, how history shapes the present, the power we have as individuals, the harm of us-versus-them mentality, and why we ought to treat others the way we’d like to be treated. All of these are important lessons to prepare children for the real world.

As it is now, almost half of American states don’t require Holocaust education. Even for states with that requirement, lessons have typically started in middle school or high school, years after kids have been exposed to antisemitism. Many students aren’t learning about the Holocaust, but with today’s technology and current challenges, they are being barraged by antisemitic conspiracy theories on social media and by people in power, including elected officials of various political leanings, and celebrities.

The results are grim. A 2020 survey showed that about two-thirds of millennials and Gen-Z were unaware that the Holocaust consisted of the murder of about six million Jews, eleven percent blamed the Jews themselves as the cause of the Holocaust, and almost half had been exposed to Holocaust denial and revisionism on the internet. And while there’s been some attention paid to antisemitism at colleges (the severity of which varies by the campus) not much attention has been on the fact that antisemitism starts way before then. In a late 2024 survey, the Anti-Defamation League noted that 71% of Jewish parents say their K-12 child was either the victim of antisemitism or saw it happen to another kid.

Now we’re seeing an uptake in everything from harassment to murder to terrorism aimed at Jewish people in America and beyond.

The truly dismal state of Holocaust and antisemitism education became apparent to me after experiencing increased antisemitism, mainly at work but also in my personal life. My boss informed me that it “wasn’t a big deal” to refer to Jewish people as Nazis. After not agreeing with her, I suddenly — and conveniently — found myself jobless. I had thought my boss was well-educated. She did like to brag about how smart she was. So how was it she couldn’t understand the Holocaust or antisemitism?

It was speaking with child Auschwitz survivor Eva Mozes Kor afterward that a profound reality dawned on me: Holocaust education needs to start with educating kids, not waiting until people are teens or adults.

Eva, as a child, had watched as her classmates turned against her because they were told to do so. She had watched as no one helped when her family was taken away and put into a ghetto. At ten, she was in the Nazi death camp Auschwitz.

“You have to reach kids before they turn twelve,” Eva told me multiple times. “After that, it’s too late, the prejudices are formed.”

I first learned about the Holocaust at home from my father when I was in elementary school, so I knew teaching it to this age range could be done. He started with background. He taught me about harassment of Jews, of Jews being put on trains. He built up to the gas chambers. That’s a good way to teach kids: build up gradually, hold their hand and answer their questions step-by-step. Be respectful of children’s intelligence while also not barraging them.

What happens when you wait until kids are older? I have some personal experience with that: After we learned about the Holocaust in eighth grade (when we were 13 or 14) a schoolmate gave me a book she said I needed to read. It included passages about the Jews that said our works were works of darkness and our doings were abominations. She had obviously been told negative things about Jews long before the school stepped in to educate on antisemitism. When I tried to talk to her about the antisemitism in this book, she only doubled down. The prejudices were already formed.

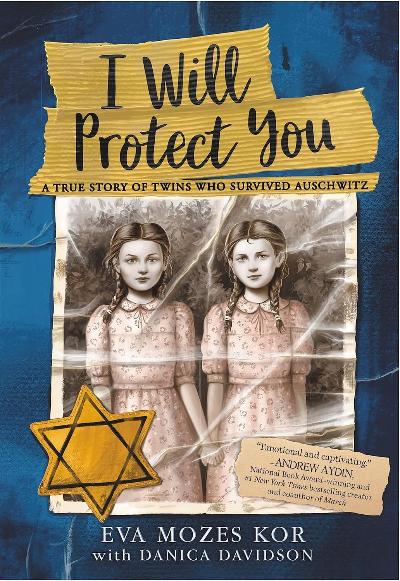

When Eva learned I was a children’s author, she said we needed to write a book aimed for elementary school about her experiences at the same age. It was to fill a gap in Holocaust and antisemitism education because so many people have been unwilling to touch the topic at that age. But because I’d known about the Holocaust almost my whole life, that made it easier for me to approach. Working with her, I wrote it the same way I learned it. Nothing graphic, but nothing sugarcoated, either.

To make the topic age-appropriate, I told it from child Eva’s point-of-view, like one child talking to another, beginning with her being bullied for being Jewish and the long history of antisemitism. I gave context and wove in history, and I built up to Auschwitz. I kept it in a child’s voice. Our book, I Will Protect You, was creating something new, an experiment to revolutionize Holocaust education. When Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum looked it over, he said that “the story of this young girl is narrated in a manner that I would not have thought possible, faithful to the history and yet accessible to young readers.” Just because it hadn’t been done before didn’t mean it couldn’t be done.

To make the topic age-appropriate, I told it from child Eva’s point-of-view, like one child talking to another, beginning with her being bullied for being Jewish and the long history of antisemitism. I gave context and wove in history, and I built up to Auschwitz. I kept it in a child’s voice. Our book, I Will Protect You, was creating something new, an experiment to revolutionize Holocaust education. When Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum looked it over, he said that “the story of this young girl is narrated in a manner that I would not have thought possible, faithful to the history and yet accessible to young readers.” Just because it hadn’t been done before didn’t mean it couldn’t be done.

It’s good for children to learn some of the harder things in life while being taught in a safe environment. At the same time, of course children should also have plenty of time to play, read fun books, and learn about more positive times in history. There is more to Jewish history than the Holocaust, so it isn’t the only thing schools ought to teach about the Jewish people, either.

I hope kids can take away the same lessons I got from learning about the Holocaust in elementary school: the patterns of antisemitism, the importance of empathy, the reality that action must be taken before things get this bad, the need to question things and not let other people do your thinking for you, the necessity of viewing people as individuals instead of prejudging them. Kids are a lot smarter than adults often give them credit for, and these are lessons they can take with them for a lifetime.