No Jews Allowed—Again

No Jews Allowed—Again

10 min read

Journey across the Red Sea to uncover whether Sheba’s queen ruled from Yemen, Ethiopia, or both—where archaeology, legend, and faith converge in one of the Bible’s greatest mysteries.

Few biblical tales have stirred the imagination across cultures as powerfully as the legendary meeting between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Told in the First Book of Kings (10:1–13), the story describes a mysterious monarch who traveled from a distant land with caravans of gold, spices, and precious stones to test Solomon with riddles and witness his famed wisdom. Her praise of the God of Israel stands out as one of the Bible’s most striking accounts of a foreign ruler recognizing Judaism’s monotheism. Equally memorable is Solomon’s generosity: the king granted her “all that she requested” before she returned to her land.

Yet, despite the vividness of the episode, the identity and location of her kingdom—known in Hebrew as Sheva—remain one of the Bible’s enduring mysteries.

Biblical scholars, historians, and archaeologists have long debated the location of the kingdom described in the story of Solomon. The two most widely accepted views place Sheba either in southern Arabia (present-day Yemen) or in Ethiopia.

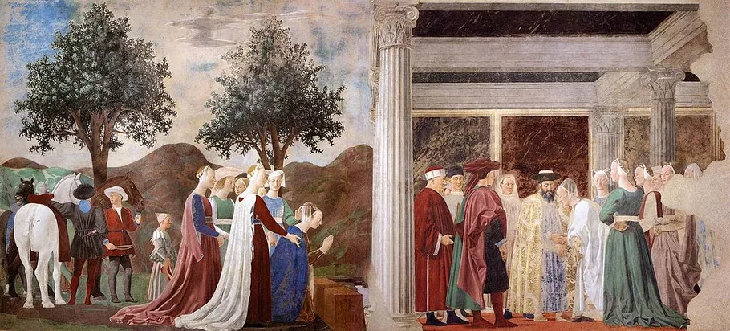

Piero della Francesca, Procession of the Queen of Sheba, ca. 1252–66. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Piero della Francesca, Procession of the Queen of Sheba, ca. 1252–66. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Proponents of the “Yemen theory” point to a historical kingdom that arose in southern Arabia during the 10th century BCE (the period usually associated with Solomon), known as the Sabean Kingdom, or simply Saba. The South Arabian script from that era lacked vowels, leaving scholars unsure whether the name was pronounced Saba, Sheva, or Sheba—but either way, the connection is striking.

The biblical story describes the queen bringing “an abundance of spices,” and Yemen was renowned throughout antiquity as a global producer of exotic spices exported to Egypt, India, Greece, and Rome. Excavations at Ma’rib, the Sabean capital, have uncovered temples, inscriptions, and irrigation works that testify to the wealth and sophistication of this incense-trading kingdom.

At the same time, Ethiopian tradition—especially preserved in the Kebra Nagast (“Glory of the Kings,” a sacred Ethiopian text written in Ge’ez)—firmly places the Queen of Sheba in present-day Ethiopia, naming her Makeda. According to legend, Makeda had a romantic relationship with Solomon (perhaps as a wife or concubine) and bore him a son, Menelik I. Ethiopia’s royal dynasties long legitimized their rule by claiming descent from Menelik I, the supposed son of King Solomon and the queen of Sheba. Some Ethiopian Jews also preserve this tradition.

Adding to the intrigue, the Bible records that the queen gave Solomon not only spices but also 120 talents of gold (about 4,000 kg or 9,000 lbs). In biblical times, the Horn of Africa was among the world’s richest gold-producing regions, and archaeology in northern Ethiopia has confirmed ancient gold mining. By contrast, Yemen never possessed significant gold deposits.

Separating Yemen from Ethiopia is the Red Sea, which may hold clues to Sheba’s true location.

Immediately before the story of Sheba, the Book of Kings describes Solomon constructing a seaport at Etzion-Geber near Eilat on the shore of the Red Sea—an event confirmed by archaeology. From there, he partnered with Hiram, the Phoenician king of Tyre, to send ships to a distant land called Ophir to obtain gold. The Phoenicians were renowned sailors, establishing colonies as far away as Spain and Morocco.

Attributed to Ira, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba page in folio from an illustrated manuscript, early 19th century. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Attributed to Ira, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba page in folio from an illustrated manuscript, early 19th century. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Given the limitations of sea travel 3,000 years ago, Ophir must have been somewhere along the Red Sea coast, not across the Indian Ocean, since no evidence exists of direct sea trade between the Middle East and India until centuries later. If Ophir was on the Red Sea coast, was it in fact on the African or Arabian side? The question matters because immediately after this account, the Bible introduces the Queen of Sheba. This may suggest that Ophir lay close to Sheba itself. Israelite sailors and miners could have carried with them stories of Solomon’s wisdom, which eventually reached the queen: “It was a true report that I heard in my country of your deeds and of your wisdom” (1 Kings 10:6).

The clearest clue may lie in Psalm 72, a prayer for the reign of King Solomon: “The kings of Tarshish and the Isles shall bring tribute; the kings of Sheba and Seba shall offer gifts” (v. 10).

The sentence structure and poetic style of the author is telling. Just as Tarshish is paired with “the Isles,” so Sheba is paired with Seba. Ancient geography helps explain this. Tarshish is widely identified with Cilicia in Asia Minor, on the Aegean coast of modern-day Turkey. The “Isles” (iyim) naturally refer to nearby Greece. The psalmist’s style is to place neighboring lands side by side. By the same logic, Sheba and Seba must also be neighbors. And indeed, across the Red Sea, Yemen and Ethiopia face one another, their ports separated by only a few days’ sail. The psalm may therefore preserve a memory of two parallel kingdoms—one Arabian, one African—linked by trade with Solomon’s Israel, but which one did the Queen of Sheba come from?

The answer to our mystery may be in the Book of Genesis, which describes the ancestral foundations of humanity’s first nations. Following the Great Flood in the time of Noah, Genesis describes humanity branching off from Noah’s three sons. The descendants of Ham are thought to have inherited the African continent, the descendants of Japheth overtook the Eurasian mega continent, and Shem (the Semites) settled in what we today commonly call the Middle East.

In describing the descendants of Ham, the Torah records: “And the sons of Cush were Seba and Havilah and Sabta and Raamah and Sabtecha; and the sons of Raamah were Sheba and Dedan (Genesis 10:7).

Frans Franken II, King Solomon Receiving the Queen of Sheba, ca. 1620–29. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum.

Frans Franken II, King Solomon Receiving the Queen of Sheba, ca. 1620–29. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum.

Throughout the Bible, Cush is known to be located in East Africa. Some scholars identify it with Sudan while others with its neighboring country to the south, Ethiopia. Following the descendants of Cush, we find Sheba! But that’s not all folks.

Later in Genesis 10:26–28, Sheba appears again, this time as a descendant of Joktan, from Shem’s line: “And Joktan begot Almodad and Sheleph and Hazarmaveth and Jerah, Hadoram, Uzal, Diklah, Obal, Abimael, and Sheba.”

Here we see some of Shem’s descendants being listed, those who settled in the Middle East, and particularly in South Arabia. The city of Hadramaut in Yemen may be a preservation of Hadoram. Ancient sources also identify Uzal with the site of Sana’a, the current capital of Yemen. And here too we have Sheba, a remnant of the Sabean kingdom.

Thus the Torah mentions Sheba in both Africa and Arabia, which only strengthens our original question…which Sheba was the queen’s?

Some scholars suggest the answer is both. In antiquity, the Red Sea was less a barrier than a bridge. Ancient Ethiopia and Yemen were so interconnected that they may have formed a united kingdom across the sea.

An Ethiopian fresco of the Queen of Sheba travelling to King Solomon.

An Ethiopian fresco of the Queen of Sheba travelling to King Solomon.

This would explain how Sheba’s queen could gift Solomon both the spices of Yemen and the gold of Ethiopia. Archaeological remains—including Sabean-style inscriptions, temples, and architecture in Ethiopia—show strong Arabian influence, while Ethiopian power also extended into South Arabia at times. Linguistically, Ethiopian Semitic languages such as Ge‘ez, Amharic, and Tigrinya trace back to South Arabian dialects. Genetic and cultural studies likewise reveal migration in both directions.

The Sabeans, renowned for monumental architecture, advanced irrigation, and the incense trade, left a clear mark on Ethiopian highland culture. Terraced farming, stone inscriptions, and even religious practices show parallels. It is entirely plausible that the Bible’s Sheba was not confined to one shore but was a trans-Red Sea realm uniting parts of both Arabia and Africa.

Returning to Kings, we read that Solomon gave the Queen of Sheba “all that she requested.” The vagueness of this verse has long invited interpretation. Was it merely material gifts, or something more?

Both Yemenite Jews and Ethiopian Jews claim to be the oldest Diaspora communities in the world, tracing their earliest foundations back to the period of Solomon. In the case of Yemenite Jews, their longstanding belief is that what the Queen of Sheba requested from King Solomon was Israelite servants to return home with her, not just as helping hands, but as spiritual guides. Those Israelite servants would have become the earliest Jewish presence in South Arabia and the oldest Jewish community outside Israel. Likewise Ethiopian Jews believe the gift Solomon bequested to the Queen of Sheba was a child, and that they literally descend from that union, marking their ancient connection to the Holy Land and to the Davidic dynasty.

Both traditions reflect deep Jewish influence. Yemenite Jews preserved piyyutim (liturgical poems), unique chanting styles, and Torah cantillation believed to date back to the First and Second Temples. Hebrew tombstones from the 4th–3rd centuries BCE found in Aden provide concrete evidence of Jews in Yemen during antiquity. Later, a Jewish kingdom arose there in the 4th–6th centuries CE, replacing references to pagan gods in inscriptions with the name of “the God of Israel, Lord of the Jews.”

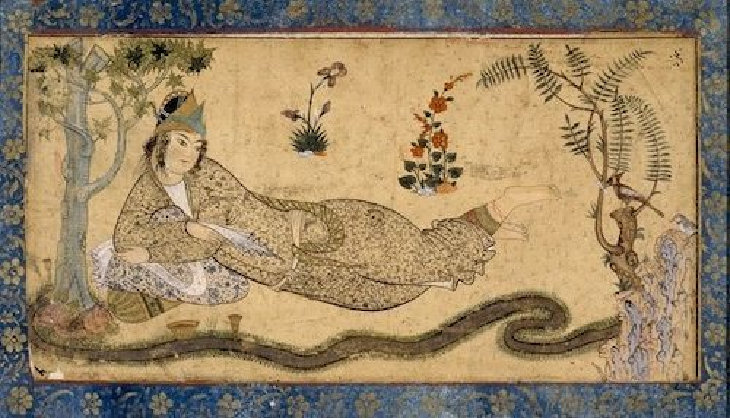

Queen of Sheba attributed to Sadiqi Beg, the superintendent of the library of the great Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I (reigned 1587-1629). British Museum

Queen of Sheba attributed to Sadiqi Beg, the superintendent of the library of the great Safavid ruler Shah Abbas I (reigned 1587-1629). British Museum

In Ethiopia, archaeological findings in Axum and Lalibela point to early Jewish influence. Genetic studies show Ethiopian Jews share Levantine ancestry blended with Cushitic roots. The Beta Israel preserved core practices such as Sabbath observance, dietary laws, and circumcision. Though isolated from rabbinic Judaism and lacking customs like tefillin or holidays like Purim, they preserved other ancient practices—such as the Passover sacrifice—long after it disappeared elsewhere.

Ethiopian tradition also maintains that Menelik I brought the Ark of the Covenant from Jerusalem to Axum, where it remains in the Church of Mary of Zion, guarded by priests. While the Bible continues to place the Ark in Jerusalem after Solomon, Midrashic sources mention a secondary Ark that was traditionally taken with the Israelites into battle, which could explain this tradition.

The journey to Sheba is more than a geographical mystery—it is a fulfillment of Biblical prophecy. Solomon’s encounter with the queen fulfilled his role as a light to the nations. The spark of Hebrew monotheism reached across the sea, planting seeds of Judaism in distant lands and giving rise to ancient Jewish communities in Yemen and Ethiopia.

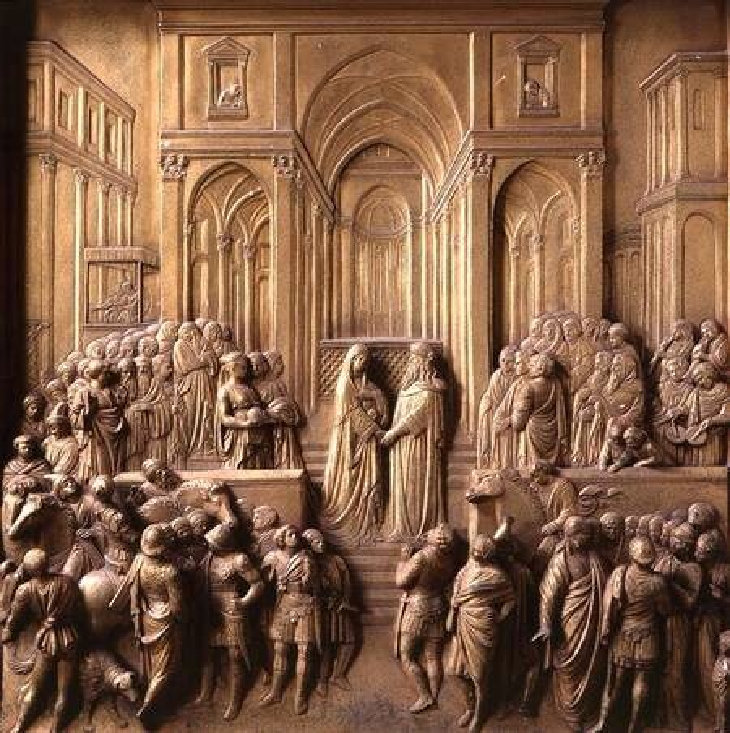

Queen of Sheba meeting King Solomon – Door of Florence Baptistry. Florence, Italy

Queen of Sheba meeting King Solomon – Door of Florence Baptistry. Florence, Italy

In the 20th century, those communities finally returned to Israel after nearly 3,000 years, reuniting with their ancestral homeland. Like two stars pulled apart by time yet bound by fate, King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba continue to meet—through history, tradition, and prophecy.

You wrote "no evidence exists of direct sea trade between the Middle East and India until centuries later." While there is no DIRECT archaeological evidence, there is the oral traditions of 2 of the many migrations of Jews into India.

The oldest group of the Black Jews of Cochin have a tradition that their ancestors were maritime traders for King Solomon and manned a trading post there, and some remained when trading ended.

The Bene Israel have the same tradition about Konkan, except that they left when trading ended, and their descendants returned centuries later during turmoil in the Land of Israel. They navigated the same route that had been passed down to them.

Some of the items from his palace came from India and we don't know if trade was direct or indirect.

Tarshish was the Tin Isles where the ingots came from which have recently been discovered in Israel and the Mediterranean. It was mined in Devon and Cornwall in south-west England. Tarshish will play a roll at 'the end times' (Ezekiel 38) and in other places.

Very interesting and beautifully written. Thank you

Great article!