Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

Passover’s Message of Hope in the Aftermath of Oct. 7

9 min read

I grew up in a religious dictatorship in Iran. My mother didn’t want me to become “brainwashed” in America.

Eight years ago, when my mother first learned that I was engaged, she shared the happy news with every friend, relative and butcher in West Los Angeles. But when she saw me clad in a stylish hat on the first night of Rosh Hashanah (I had been married three months earlier) she gently pulled me aside, handed me a steaming platter of Persian saffron rice and said, “I just want you know that if you ever wear a wig, I’ll kill myself.”

This maternal half-threat will resonate with many in my Iranian American Jewish community in Los Angeles, home to the largest Iranian diaspora in the world. It may even ring a bell with non-Iranian Jews who grew up in non-Orthodox or secular homes and became religious and must now navigate a delicate, often comedic balance between living Torah-observant lives and maintaining a good relationship with their less observant parents.

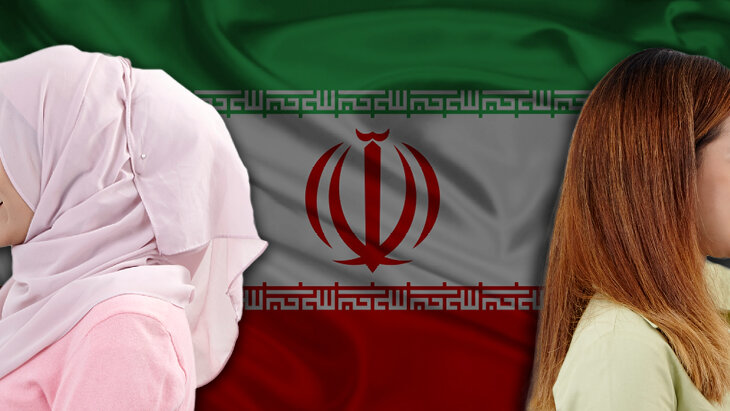

My mother and me

My mother and me

Like tens of thousands of Iranian Jews, I grew up in a traditional Jewish home. Intermarriage with a non-Jew was unfathomable and Shabbat dinners with family members was unabashedly sacrosanct. No one, whether 17 or 70, dared to make plans on Friday evenings other than attending a Shabbat dinner.

But we had an interesting way of sanctifying Shabbat: My mother would light Shabbat candles, my father would recite the prayers over wine and bread as our guests impatiently salivated over the intoxicating scents of Persian stews and rice, and once the prayers ended, we each made ourselves a heaping plate of food and proceeded to run toward the television set. I grew up in the 1990s and my earliest memories of Shabbat in this country include enjoying dozens of stuffed grape leaves while watching the Los Angeles Lakers on TV. But our family had the same Shabbat evening practice in post-revolutionary Iran: We grabbed our plates of Persian delicacies and ran to the television set to scoff at state-sponsored, propaganda “news” programs.

Back in Iran, some Jewish communities in various cities were famously known to be more religiously observant than others. But there was an unspoken understanding among many in Iran's Jewish community that as minorities who were persecuted for several millennia, we had “paid our dues” and didn’t necessarily need to adhere to Orthodox Judaism.

Arriving in America, suddenly the guarantee of Jewish continuity seemed dangerously fragile.

Indeed, we were minorities within a minority; Iran is roughly 99% Shi’ite Muslim and Jews constitute a tiny percentage of that remaining one percent, which also includes Christians, Baha’is and Zoroastrians. For hundreds of years, many in the greater Muslim community treated Jews as ritually impure, and Jews seldom married non-Jews. With intermarriage virtually non-existent and a community that had maintained unbreakable Jewish continuity for 2,700 years, living according to strictly Orthodox Jewish practice seemed superfluous.

But that all changed when nearly 90 percent of Iran’s former Jewish community of 100,000 left the country after the 1979 Islamic Revolution that turned Iran into a fanatic Muslim theocracy. Suddenly, the guarantee of Jewish continuity seemed dangerously fragile once many of us arrived in America. It was in this country where I first learned that some Jews frequent movie theaters on Friday nights, others seldom wince when ordering bacon sandwiches, and still others marry non-Jews and enjoy bacon appetizers during their Friday night weddings. I had never seen such things in Iran.

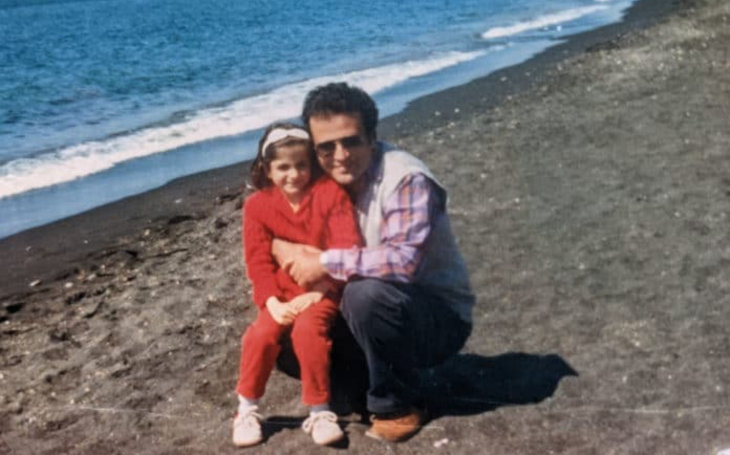

Me and my father, 1989

Me and my father, 1989

My family (and ironically, my mother) is unabashedly proud of our Jewish identity; we also feel deeply entitled to it, given the brutal hardships that Persian Jews faced for millennia. Our Jewish identity is undoubtedly our primary identity.

But growing up in the United States, I never attended Jewish day school (or even Sunday school) because those experiences were unattainable luxuries for my refugee family. My knowledge of Judaism hovered somewhere between the realms of “We’ve always done it this way” traditionalism and “What we practice is enough” resignation. In America, we hung a large, metal mezuzah on the doorpost of our apartment, but never bothered to check whether the scroll inside was kosher. That about sums up my Jewish upbringing: fiercely proud and traditional, but not adhering to the nitty-gritty details of Jewish law.

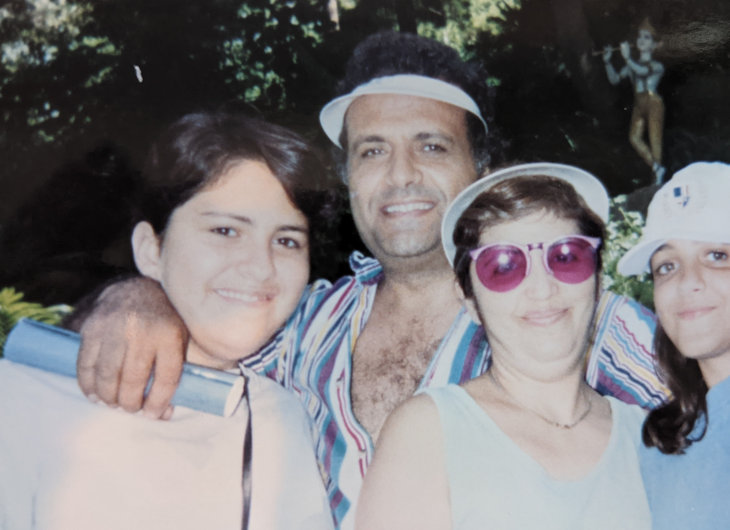

My family in America

My family in America

And then, it happened: I went to college in a small town in northern California and some of my peers who had never met a Jew began asking me a variety of questions about Judaism. I was mortified because for years I had prided myself on mastering secular studies, particularly American history, and yet, I possessed the Jewish fluency of a small child. In America, I had been enrolled in over half a dozen Advanced Placement (AP) classes and could easily reference facts about Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, but when it came to Judaism, I didn’t know Maimonides from Moses.

Everything I knew about the Passover story was derived from watching annual re-runs of Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Ten Commandments” while enjoying heaping platefuls of Persian rice, stew and matzah during TV breaks at our family seder.

I realized something was missing. I needed many more answers about what it meant to be Jew.

One day, during my freshman year in Fall 2001, I discovered a copy of Isidore Fishman’s 1978 book, Introduction to Judaism on a bookshelf at our campus Hillel house and spent the next three weeks teaching myself about Jewish values. After two years, I transferred to another university in southern California, where I became very active in Jewish life and even learned to read rudimentary Hebrew with the help of the Hillel executive director.

Upon completing my undergraduate studies, I moved back to Los Angeles and felt a palpable lack of Jewish life, given that I had “graduated” from weekly Hillel Shabbat dinners and events. My older sister urged me to visit a synagogue called Aish on Pico Robertson.

At Aish I met dozens of other young, Jewish students and professionals who had grown up in non-Orthodox communities and were open to learning more about Jewish values through engaging, soul-touching classes. I met local families who kindly hosted me and other young professionals for Shabbat lunches where I was irreversibly inspired by experiencing the difficult yet rewarding weaning off of work, driving and other mundane tasks on Shabbat.

In 2009, I spent several illuminating weeks in Jerusalem at Aish’s JEWEL program, which offers introductory, holistic learning, and tours and day trips for young women. In that lovely, Socratic-style lecture space in Ramat Eshkol, I had never felt so at home.

My mother didn’t know what to think. She begged me to continue to eat at her home when I returned, called incessantly to ensure I hadn’t been “brainwashed,” then called again to ask me to pray fervently for our family at the Western Wall and to bring back Shabbat candlesticks from Israel. I loved her ambivalence.

During my first week at JEWEL, I sat beneath an olive tree, gazed at the sun-kissed Jerusalem hills and began reading the section of the Torah where God instructs Abraham, “Go to yourself…to the land that I will show you” (Genesis 12:1). Beneath the shade of that serene Jerusalem garden, I found my essence.

I explained that no one was forcing me to commit to Jewish growth; I wasn’t being brainwashed and my world wasn’t shrinking. In fact, it was expanding.

I was connecting with my true self, but I also understood my mother’s fears, which were twofold: First, she believed that if I adhered to stricter interpretations of halacha, Jewish law, I would seemingly nullify her own Jewish practices, rendering them “not enough.” Second, my mother feared that my growing religious observance would create an irreparable gap between us.

When I returned home to Los Angeles, I invited my mother and father to my apartment for Shabbat dinner; I wanted my mother to know that we could still be together for Shabbat meals (and as an added perk, she wouldn’t have to strain herself cooking because I was the host). That night, I spoke to her and acknowledged that given her trauma (and mine) in post-revolutionary Iran, where religious fanaticism was violently forced upon us, I empathized with why she was so distrustful and afraid of any religious observance that she perceived as “too much.” I explained that no one was forcing me to commit to Jewish growth; I wasn’t being brainwashed and my world wasn’t shrinking. In fact, it was expanding.

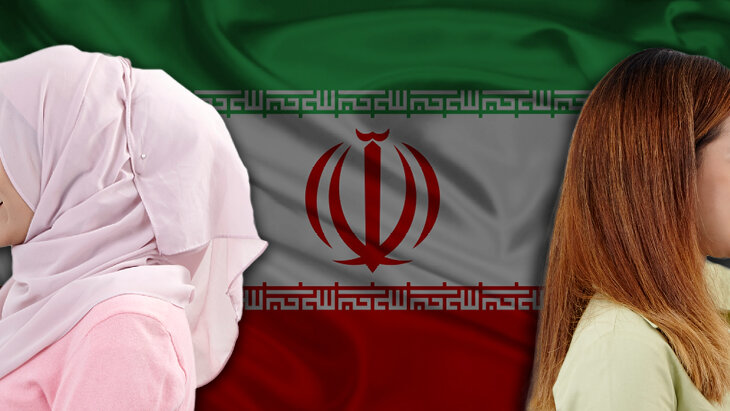

Married me, note the hat

Married me, note the hat

My mother was compassionate, but skeptical. But I held firm to the belief that like the intersection of a Venn Diagram, there was space for my Jewish growth to not only exist alongside, but actually include my parents. Afterall, I wasn’t converting to a new religion; I was returning (the literal meaning of teshuvah, often grossly mistranslated as “repentance”) to the way of life our family had upheld and cherished for millennia.

My mother is sensitive to head coverings, especially wigs, because we were forced to wear the mandatory hijab, or Islamic head covering, back in Iran.

In the years since I returned to Los Angeles, I married an Iranian American Jew who also came to traditional observance later in life, and we’ve hosted countless Shabbat and Yom Tov meals. My mother began keeping a strictly kosher home, initially to host her children (and grandchildren). One afternoon, she casually noted, “I also wanted to make the kitchen kosher for myself and your dad.”

We grew closer because she now understood my world. For my part, I recognized her story. My mother was still sensitive to head coverings, especially wigs, because we were forced to wear the mandatory hijab, or Islamic head covering, back in Iran. Once married, I compromised and bought stylish hats.

My journey of growth and learning remains continuous, but it’s anchored by an eternal instruction God gave to Abraham, the first Jew: “Go to yourself.” Even if, every now and then, you have to take your mother along on the journey with you.