Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

9 min read

The inside story of a rebellious Jewish sect that began in the Middle Ages.

A popular legend from the medieval period depicts the founding of Karaism to a bitter dispute over the office of the exilarch, the political leader of the Jewish community in Babylonia. Anan Ben David was supposedly qualified for the office but was passed over due to his independence and untrustworthiness. Out of jealousy, Anan gathered together what were left of the sectarians from the Second Temple period, such as the Sadducees, and established a new Jewish sect: the Karaites. Charged with treason and placed in jail, Anan met a prominent Muslim scholar who greatly influenced the development of his new religious sect.

While little of this account is viewed as reliable by historians, and the influence of Islam on Karaism is a controversial academic question, it is generally accepted that in the 8th century a Jewish scholar named Anan abandoned the Babylonian rabbinic academies and composed a Talmud of his own. Like the Babylonian Talmud, Anan’s Talmud is written in Aramaic, and small fragments exist to this day. The students of Anan did not call themselves “Karaites,” but were rather known as “Ananites” or “followers of Anan” and it was not until the 9th century that evidence of communities calling themselves “Karaites” is found.

The Karaites rejected the Oral Torah, a central pillar of Judaism.

The major distinction between Ananites and Karaites, versus the Rabbinic Jewish community, is that Anan and his followers rejected the belief that two Torahs were given by God to Moses at Mount Sinai and taught to the entire Jewish people: a Written Torah, containing the five books of Moses; and an “Oral Torah” in which the details of the written Torah were explained in detail. Faith in the Oral Law whose details were transmitted orally from Moses to Joshua to the present generation of Torah scholars is a central pillar of Judaism. Thus, Anan struck at the core of Jewish faith and survival.

By rejecting the authority of the Oral Torah and the rabbinic leaders who transmitted its teachings, Anan created a new sect based in his view that religious truth emerges from independent study of the Written Torah alone. In other words, in cases where details of Jewish practice are transmitted exclusively via the Oral Torah, Anan insisted that such traditions are mistaken. Instead, he propounded the belief that all of the Torah’s commandments must be derived from a careful examination of its verses alone.

A Karaite kenesa [synagogue], Vilnius, built in 1921.

A Karaite kenesa [synagogue], Vilnius, built in 1921.

A famous slogan epitomizing Anan’s revolution is “search scripture well and do not rely on my opinion.” Later Karaite groups in the medieval period, following in Anan’s footsteps, turned this motto into a principle of faith that each individual Jew in every generation is obligated to interpret the Torah’s commandments on their own.

If such a philosophy sounds like it would lead to chaos, or “two Jews three opinions,” you would be correct. The 10th century Iraqi Karaite Jacob al-Qirqisānī records a lengthy list of disputes within the Karaite community, and complains that the amount of disagreement amongst Karaites is constantly growing and is driven by jealousy and ego amongst Karaite leaders. Even for matters as basic to Jewish life as the calendar, it would not be unusual for two Karaites in the same community to calculate different days and even months for the Jewish holidays because each one observed the new moon on a different day, or observed the ripening of barley (used by Karaites to determine the spring or month of Nisan for celebrating Passover) in a different period.

It would not be unusual for two Karaites in the same community to calculate different days and even months for the Jewish holidays.

By contrast, the leaders of the Rabbinic community – the Geonim – established a fixed calendar in the medieval period so that all Jews around the world would celebrate the holidays on the same day. al-Qirqisānī describes the Ananites as so bitterly divided over the issue of the calendar, that members of their sect refused to eat meals with each other if they disagreed over the calculation of the calendar or any other detail of Anan’s law.

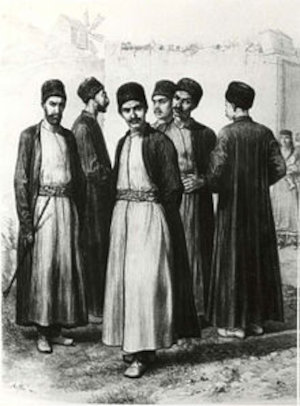

A group of Karaites, from Description ethnographique des Peuples de la Russie (Theodore de Pauly, 1862).

A group of Karaites, from Description ethnographique des Peuples de la Russie (Theodore de Pauly, 1862).

Many of the interpretations that Anan and subsequent generations of Karaites found in the Torah were similarly disruptive for the continuity of Jewish practice since antiquity. For example, Anan interpreted the story of Israel’s circumcision at Gilboa to conclude that “knives of flint” (Joshua 5:2) implies that circumcision must be performed with scissors rather than a knife. He justified this view on the basis that “knives” is in the plural, and thus understood that the circumcision tool must have multiple parts i.e., a scissor with two blades and not a knife with a single blade.

Even the later Karaites were very critical of this interpretation, because it was obvious that in the thousands of years of Jewish history, nobody had heard of circumcision scissors. Indeed, one Karaite points out that “knives” is in the plural in the story of Joshua because thousands of Jews were being circumcised at the same time and thus many knives were needed.

The ancient details regarding tzitzit and what to write inside the boxes of tefillin were rejected by Karaites, as were the identity of the plants used for the four species on Sukkot.

In addition to new interpretations of biblical verses, Anan and the Karaites also rejected many details of Judaism that have no explicit biblical description but are included in the Oral Torah. For example, the ancient details regarding how to tie tzitzit and what to write inside the boxes of tefillin were rejected by Karaites, as were the identity of the plants used for the four species on Sukkot and the guidelines for building a legal Sukkah and many more details of the commandments. Some aspects of post-biblical Judaism, such as the holiday of Hanukkah are not observed by Karaites for the same reason.

Moreover, some aspects of Torah law that are understood in the Oral Torah as non-literal, such as the understanding that the punishment of an “eye for an eye” means monetary compensation, were re-interpreted as literal punishments by some Karaites.

Karaite men in traditional garb, Crimea, 19th century.

Karaite men in traditional garb, Crimea, 19th century.

As a result of the Karaite commitment towards utilizing the Written Torah as the sole basis of their legal traditions, Karaites in the Middle Ages produced many biblical commentaries and treatises on Hebrew grammar designed to understand the Torah’s language as precisely as possible. For example, a Karaite from Jerusalem, Japheth Ben Eli, is credited by historians as the first author to complete a commentary on all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible in the second half of the 10th century. Japhet’s commentary and other Karaite works on Hebrew grammar were studied by some of the most influential Rabbinic commentators on the Torah such as Ibn Ezra, who occasionally cites Japhet’s views anonymously in his biblical commentary.

The chief opponent of Anan and the Karaites in the medieval period was Saadia Gaon, who wrote several books challenging Karaism from the beginning to the end of his long scholarly career. Most of these books, written in Arabic, have unfortunately been lost. From the fragments that have survived, it is clear that Saadia was diametrically opposed to the heart of Karaite ideology – that each Jew is obligated to interpret the Torah on their own.

Those who were physically and proximally closer to God’s revelation to the entire Jewish people at Sinai – the sages of the Mishna and Talmud - necessarily earn a higher degree of authority in Judaism than later generations.

Rather, Saadia pointed out that Judaism, like any other mature legal system, builds upon the efforts of earlier generations and does not start from scratch in each generation. Those who were physically and proximally closer to God’s revelation to the entire Jewish people at Sinai – the sages of the Mishna and Talmud - necessarily earn a higher degree of authority in Judaism than later generations.

At the outset of Anan’s activity until the 10th century, Saadia and other Babylonian Jewish leaders fiercely opposed Anan and his followers and banned marriages and other communal intermingling between Rabbinic Jews and Karaites. In subsequent centuries, however, attitudes towards Karaites relaxed as the “threat” of Karaism dwindled and it became clear that the Karaites were destined to become a small minority splinter group. Evidence unearthed in the 20th century from the Cairo Geniza, such as marriage documents, letters, and donation slips, indicate that Rabbinic Jews and Karaites in medieval Egypt of the 11th-12th centuries had a higher degree of social cohesion than previously understood -- and the various legal questions concerning the status of Karaites in Judaism remain complex and debated amongst rabbinic scholars to this day.

Nowadays, the Karaites survive as a small minority group of approximately 40,000 individuals in Israel, with smaller communities in the United States and Europe. Most of today’s Karaites are descendants of the Egyptian Karaite community, with smaller communities from Eastern Europe, Turkey and Iraq.

Karaite Congregation B’nai Israel in Daly City, California

Karaite Congregation B’nai Israel in Daly City, California

The face of Karaism has changed dramatically since the medieval period. Karaism developed its own set of customs and beliefs over the generations and is significantly less “revolutionary” in encouraging each individual in each generation to discover the truth on his own. Like other minority groups in Israel, such as the Samaritans, many Karaites have assimilated into the fabric of Israeli society and the future of Karaism is uncertain at best.

The medieval Karaites left an indelible mark on medieval Judaism and its intellectual culture. Rather than defeating the Oral Torah, they only strengthened the faith in its necessity for Judaism, as Proverbs says, “It’s a tree of life to those who hold fast to it, and those who uphold it are happy. Its ways are pleasant and all of its paths are peaceful” (3:18).

Are Karaites considered Jewish according to the Halakha? What is their status?