Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

14 min read

The shofar has become the voice of the Jewish people at different occasions throughout history.

While unverified and undocumented, is nevertheless a widespread legend amongst Jews and is cited by the author Eliyahu Kitov in his famous Book of Our Heritage.

This story is supposed to have occurred in 1497, five years after the expulsion of Spain’s Jews. The Jews who remained in Spain were converts to Christianity, many of whom secretly practiced some Judaism in secret. These crypto-Jews were known as conversos, anusim (Hebrew for “those coerced”) or by the derogatory term, Marranos. One of these conversos was a musician, Don Aguilar.

He announced that on Sunday, the 5th of September, he would personally lead an orchestra in Barcelona in a novel concert of his own composition. The piece he wrote would be a celebration of native peoples and their cultures. Exotic instruments from around the world would be utilized in the composition. Many secret Jews came to the concert because that date was Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year, and one of the “exotic” instruments was a ram’s horn.

The horn was played by another converso, who sounded the traditional notes of the shofar blowing in synagogues throughout history and around the world, Tekiah, shevarim, teruah, tekiah.1 Most of the audience appreciated this virtuoso performance of a “primitive” and unfamiliar instrument. However, for the secret Jews in the audience, Don Aguilar’s “music” gave them their first chance in years to fulfill the commandment of hearing the Shofar.2

I cannot attest to the historicity of this story, but I can attest to many examples of Jews going to extraordinary lengths to preserve their heritage under every condition, as we shall see.

Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Meisels discusses his Rosh Hashanah experience in Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944:

“The experience of one transport that left Auschwitz is seared in my memory. With the grace of God, I was miraculously able to bring a shofar into the camp. On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, I went from block to block, shofar in hand, to sound the tekiyot3. This put my life in danger, and I had to avoid the Nazis and malevolent Kapos.4 I thank God that due to His mercy and compassion I was privileged to sound the shofar that Rosh Hashanah some twenty times, coming to a hundred blasts in total. This revived the spirits of the shattered camp inmates and gave them some peace of mind knowing that at least they could observe one mitzvah in Auschwitz – that of shofar on Rosh Hashanah.

“I can still hear reverberating in my ears the sobs that burst forth from those thousand people during the tekiot. I especially remember the trembling voice of the well-known Chassid who announced the sounds before I blew them. He was Rabbi Yehoshua Fleischman, may God avenge his death, from Debrecen, Hungary, who called out the notes in a piercing wail, tekiah, shevarim-teruah, tekiah. I could barely concentrate…

“The boys who were locked in the block and were about to be sent to the crematoria found out that I had a shofar. I heard shouts and entreaties emanating from their block imploring me to come to them and sound the one hundred blasts of the shofar so they could fulfill this precious mitzvah (commandment) on Rosh Hashanah in their last moments of life, before they would be martyred and sanctify the Name of God.

“I was beside myself and completely confounded, because this involved a tremendous risk since it was nearing twilight, a dangerous hour, and the Nazis would be coming to take them. If the Nazis were to suddenly show up while I was in there with the youngsters, no doubt they would take me to the crematoria as well. The Kapos, so famous for their ruthlessness, would not let me escape. I stood there weighing the situation and trying to decide what to do. It was very doubtful that I should take the risk to blow the shofar for the boys in such a dangerous situation, and it was not clear that the risk would be justified even if there were some doubts about the danger. But the youths’ bitter supplications were heart-piercing. ‘Rebbe, rebbe! Please for the sake of God have pity on our souls. We beg you to enable us to observe this mitzvah in our last moments.’ I stood there immobile. I was all alone in my decision….

If truth be told, my decision was probably at variance with the strict law which rules that you do not endanger yourself, or even put yourself slightly at risk, to perform the mitzvah of shofar….”5

At the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel, survivors recounted that Rosh Hashanah. Menachem Brickman, a boy from Lodz taken to Auschwitz when the ghetto was liquidated, described the experience:

The sound of eternity has burst forth even in Auschwitz.

“Suddenly, a sound—a sharp, ongoing sound that hits me. All at once I become tense and listen to the sound, which casts me back to my father’s house. But the sound is already gone… For a moment I think it was an illusion. A shofar? A shofar being blown in Auschwitz. But the thought races through my head. If there’s a shofar, maybe there is still hope. I turn to one of the men and ask him in Yiddish, ‘Vas iz dos?’ (What is this?) ‘A shofar,’ he tells me. ‘It’s Rosh Hashanah today.’ Rosh Hashanah, I think to myself. A shofar being blown on Rosh Hashanah. Right under the Nazis’ noses. Something about the blowing instills in me renewed hope. The sound of eternity has burst forth even in Auschwitz. I keep wondering who blew the shofar and how he managed to smuggle a shofar into Auschwitz. It seems like a tremendous miracle to me. A small light in the dark of night.”6

During the British Mandate over Palestine, the British wanted to quash any Jewish nationalism and Jewish claims to the Land of Israel. One of the most dramatic examples of shofar blowing was performed by Rabbi Moshe Segal (1904-1985) during the British Mandate. He describes it in his memoirs:

“In those years, the area in front of the Kotel (the Western Wall) did not look as it does today. Only a narrow alley separated the Kotel and the Arab houses on its other side. The British Government forbade us to place an Ark, tables or benches in the alley; even a small stool could not be brought to the Kotel. The British also instituted the following ordinances, designed to humble the Jews at the holiest place of their faith: it is forbidden to pray out loud, lest one upset the Arab residents; it is forbidden to read from the Torah; it is forbidden to sound the shofar on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The British Government placed policemen at the Kotel to enforce these rules.

“On Yom Kippur of that year [1930] I was praying at the Kotel. During the brief intermission between… prayers, I overheard people whispering to each other: ‘Where will we go to hear the shofar? It'll be impossible to blow here. There are as many policemen as people praying...’ The Police Commander himself was there, to make sure that the Jews will not, God forbid, sound the single blast that closes the fast.

“I listened to these whisperings, and thought to myself: Can we possibly forgo the sounding of the shofar that accompanies our proclamation of the sovereignty of God? Can we possibly forgo the sounding of the shofar, which symbolizes the redemption of Israel? True, the sounding of the shofar at the close of Yom Kippur is only a custom, but "A Jewish custom is Torah"! I approached Rabbi Yitzchak Horenstein, who served as the Rabbi of our ‘congregation,’ and said to him: ‘Give me a shofar.

‘What for?’

‘I'll blow.’

‘What are you talking about? Don't you see the police?’

‘I'll blow.’

“The Rabbi abruptly turned away from me, but not before he cast a glance at the prayer stand at the left end of the alley. I understood: the shofar was in the stand. When the hour of the blowing approached, I walked over to the stand and leaned against it.

“I opened the drawer and slipped the shofar into my shirt. I had the shofar, but what if they saw me before I had a chance to blow it? I was still unmarried at the time, and following the Ashkenazic custom, did not wear a tallit (prayer shawl). I turned to person praying at my side and asked him for his tallit. My request must have seemed strange to him, but the Jews are a kind people, especially at the holiest moments of the holiest day, and he handed me his tallit without a word.

“I wrapped myself in the tallit. At that moment, I felt that I had created my own private domain. All around me, a foreign government prevails, ruling over the people of Israel even on their holiest day and at their holiest place, and we are not free to serve our God; but under this tallit is another domain. Here I am under no dominion save that of my Father in Heaven; here I shall do as He commands me, and no force on earth will stop me.

“When the closing verses of the concluding prayer – ‘Hear O Israel,’ ‘Blessed be the name’ and "The Lord is God’ -- were proclaimed, I took the shofar and blew a long, resounding blast. Everything happened very quickly. Many hands grabbed me. I removed the tallit from over my head, and before me stood the Police Commander, who ordered my arrest.

“I was taken to the… prison in the Old City, and an Arab policeman was appointed to watch over me. Many hours passed; I was given no food or water to break my fast. At midnight, the policeman received an order to release me, and he let me out without a word.

“I then learned that when the chief rabbi of the Holy Land, Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook, heard of my arrest, he immediately contacted the secretary of High Commissioner of Palestine, and asked that I be released. When his request was refused, he stated that he would not break his fast until I was freed. The High Commissioner resisted for many hours, but finally, out of respect for the Rabbi, he had no choice but to set me free.

“For the next 18 years, until the Arab conquest of the Old City in 1948, the shofar was sounded at the Kotel every Yom Kippur. The British well understood the significance of this blast; they knew that it will ultimately demolish their reign over our land as the walls of Jericho crumbled before the shofar of Joshua, and they did everything in their power to prevent it. But every Yom Kippur, the shofar was sounded by men who know they would be arrested for their part in staking our claim on the holiest of our possessions.”7

The next shofar is one of liberation and exaltation and took place at the Western Wall, but this time on June 7th, 1967, during the Six Day War. Below is a transcript of a live radio broadcast of that dramatic and joyous occasion:

“Yossi Ronen (reporter for Israeli Army Radio): We are now walking on one of the main streets of Jerusalem towards the Old City. The head of the force is about to enter the Old City.

[Gunfire.]

Yossi Ronen: There is still shooting from all directions; we’re advancing towards the entrance of the Old City.

[Sound of gunfire and soldiers’ footsteps.]

[Yelling of commands to soldiers.] [More soldiers’ footsteps.]

The soldiers are keeping approximately 5 meters between them. It’s still dangerous to walk around here; there is still sniper shooting here and there.

[Gunfire.]

We’re all told to stop; we’re advancing towards the mountainside; on our left is the Mount of Olives; we’re now in the Old City opposite the Russian church. I’m right now lowering my head; we’re running next to the mountainside. We can see the stone walls. They’re still shooting at us. The Israeli tanks are at the entrance to the Old City, and ahead we go, through the Lion’s Gate. I’m with the first unit to break through into the Old City. There is a Jordanian bus next to me, totally burnt; it is very hot here. We’re about to enter the Old City itself. We’re standing below the Lion’s Gate, the Gate is about to come crashing down, probably because of the previous shelling. Soldiers are taking cover next to the palm trees; I’m also staying close to one of the trees. We’re getting further and further into the city.

[Gunfire.]

Colonel Motta Gur announces on the army wireless: The Temple Mount is in our hands! I repeat, the Temple Mount is in our hands!

All forces, stop firing! This is the David Operations Room. All forces, stop firing! I repeat, all forces, stop firing! Over….

Yossi Ronen: I’m driving fast through the Lion’s Gate all the way inside the Old City.

Command on the army wireless: Comb the area, discover the source of the firing. Protect every building, in every way. Do not touch anything, especially in the holy places.

[Lt.- Col. Uzi Eilam blows the Shofar. Soldiers are singing ‘Jerusalem of Gold’.]

Yossi Ronen: I’m walking right now down the steps towards the Western Wall. I’m not a religious man, I never have been, but this is the Western Wall and I’m touching the stones of the Western Wall.

Soldiers: [reciting the blessing: Blessed are You Lord God King of the Universe who has sustained us and kept us and has brought us to this day!

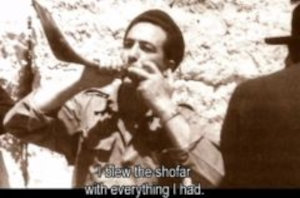

Rabbi Goren blowing the shofar

Rabbi Goren blowing the shofar

Rabbi Shlomo Goren (Chief Rabbi of the IDF): Blessed are You our God, who comforts Zion and builds Jerusalem]

Soldiers: Amen!

[Soldiers sing ‘Hatikvah’ next to the Western Wall.]

Rabbi Goren now recites a prayer for fallen soldiers [Soldiers and reporter weep in the background]

Rabbi Goren sounds the shofar, with the sounds of gunfire in the background.

Rabbi Goren: This year in a rebuilt Jerusalem! In the Jerusalem of old!8

The shofar of Inquisition-era Spain represents the eternal Jewish spark that cannot be extinguished and the flame of Judaism within every Jew that has enabled our continuity despite everything.

The shofar of Auschwitz is a cry of faith in God from the depths of the soul - even in the depths of hell.

The shofar at the Kotel under the British Mandate is the shofar of defiance and determination, two features of the Jewish people that were instrumental in building the State of Israel.

The shofar at the liberation of the Old City is a shofar of triumph and joy as the Jewish people return home and rebuild our ancient homeland and capital city.

The final shofar is not of history but of the future. In the central prayer of Jewish liturgy, the Silent Prayer, also known as the Eighteen Blessings, we say “Sound the great shofar for our liberty, and raise a banner to gather our exiles, and gather us together quickly from the four corners of the earth. into our Land. Blessed are You, God, Gatherer of the dispersed of His people Israel.” What is this “great shofar” to which the prayer refers?

I believe that the “great shofar” is composed of all the smaller shofars of our history – from Spain, Auschwitz, Jerusalem, and every synagogue in the world – all which will be joined together into the “great shofar” which will, in the words of the Bible, “proclaim liberty throughout the land for all its inhabitants thereof.”