Iran’s Attack on Israel

Iran’s Attack on Israel

15 min read

Many pillars of Jewish belief are impossible to comprehend without studying Kabbalah. So why is it so misunderstood?

Kabbalah, from the Hebrew word, mekabel (מקבל), is received knowledge or wisdom. According to Jewish tradition, kabbalistic wisdom is as old as Judaism, and its mysteries are embedded within the text of the Torah. Its secrets were known to the Jewish patriarchs1 featured in the book of Genesis, and Moses passed its lessons on to his students. Kabbalistic experiences are referenced throughout the books of the Bible, and discussed, albeit obliquely, in later rabbinic writings.

In the Talmud, kabbalistic wisdom is referred to as the “Workings of the Chariot (מעשה מרכבה),” in reference to Ezekiel’s vision (Ezekiel 1:1-28), and the “Workings of Creation (מעשה בראשית),” which explains the deeper insights and secrets alluded to in the opening chapters of the book of Genesis. Kabbalah is also considered the highest level of “the Orchard,” or “Pardes (פרד׳ס),” which is an acronym referring to the four levels of Jewish wisdom,2 the highest level being the secrets, or “Sod (סוד)”, which means “secret” in Hebrew.

Kabbalah is the study of how to understand and relate to God — how He created and maintains the world, and the paradox of finite, yet independent, existence despite His omnipotence — and is vital to comprehending many of the Torah’s commandments; the fundamentals of Jewish belief; and the organization, arrangement, and meditative aspects of formal Jewish prayer.

Kabbalistic wisdom falls into three general categories: theoretical, meditative, and practical.

Theoretical Kabbalah, which is the most studied and well-known, discusses — as mentioned above — the basics of how God, who is wholly unknowable, created, sustains, and runs the universe; the process of how that came to be; and an understanding of how to use that information when contemplating your place in the world and your relationship with God.

Meditative Kabbalah, which uses various devices and tools, is a system of spiritual liberation,3 and, especially since the rise of the Hasidic movement in the 18th century, employs a number of techniques, and in particular those centered around prayer.

Practical Kabbalah is for the most part no longer studied, and many of the leading kabbalistic figures discourage its usage. It focuses on things like chiromancy, physiognomy, astrology, amulet writing, and the like, although it does also delve into deeper mysteries, and its usage is documented in a number of places in the Talmud.4

The term, “Kabbalah,” is from the Hebrew word, mekabel (מקבל), which means to receive. According to Jewish tradition, Kabbalah is an essential part of the received wisdom God gave to the Jewish nation at Mount Sinai (as chronicled in Exodus 19 and 20).

On a deeper level, a person who studies Kabbalah is called a mekubal (מקובל), which means “one who receives.” The student of Kabbalah—like any student of Torah—needs to show great humility, as if he’s a vessel open to receiving new, pure information, who’s uninfluenced by his innate biases, prejudices, or an overinflated sense of self.

Kabbalah is central to Jewish belief and practice, and is essential to understanding many foundational Jewish ideas.

According to the great medieval thinker, Rabbi Moses Maimonides, the highest level of wisdom is comprehending God’s oneness. More than knowing that God exists, and greater than not believing in other powers, is understanding that God’s existence is the only existence. Nothing exists other than God.

That’s not just an interesting idea, it’s the point of Judaism, so much so that you're commanded to meditate on, and to contemplate, that idea at least twice a day.

That meditation is called the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4), “Listen, Israel. God is our Lord. God is one,” and you’re expected to say it every morning and evening. It’s also what’s written on a mezuzah, which is affixed to the doorposts of a Jewish house; it’s written on the parchment that’s placed inside tefillin; it’s one of the first things you’re supposed to teach your children; and it’s the last words you’re expected to say before you die.

The concept of God’s oneness is impossible to understand without Kabbalah. In Jewish thought, God doesn’t change.5 Relative to God (or from God’s perspective), creating the world changed nothing.6 God is who He is. What did change is the concept of “perspective.” The creation of the world is, in reality, simply the ability of the world’s inhabitants (i.e. you), to perceive themselves as separate, or independent, from God.7

That’s not an illusion. That’s real. You’re real. You perceive yourself as independent, have the free will to choose, and the ability to act upon those choices. But that’s only from your perspective. From God’s perspective, nothing’s changed.8

God did that in order to enable man to earn eternal pleasure; and the ultimate, eternal, only true pleasure is attachment to God.9 God is all there is. However, God gave a semblance of autonomy to man. You have a mind of your own, and that gives you the opportunity to discover your true source (God), and receive pleasure from your awareness of God’s presence. The challenge of being a physical human being is seeing past that perception of autonomy, and discerning the truth of God’s existence.

That idea is expressed in the Torah.10 Kabbalah makes it possible to understand and appreciate its depth. More than that, the Shema (mentioned above) is a commandment—you are commanded to “know God is one”—and that is impossible to do without Kabbalah.

That need for kabbalistic understanding holds true for many other important Jewish ideas as well.

Kabbalah isn’t a book, it’s an area of study, and thousands of texts deal with its subject matter. Those texts were written and compiled over a period of more than 2,000 years, and continues until today. The most important and well-known kabbalistic works include:

Sefer Yetzirah: or the Book of Creation, this ancient text deals with the Hebrew alphabet, letter permutations, and different names of God; and explains some of the deeper mysteries of the creative process. Rabbinic tradition attributes authorship to the biblical patriarch Abraham.11 Other sources indicate it may have been worked on, or restructured, by the Talmudic sage, Rebbe Akiva (he died in the year 135), and his contemporaries.12

The Bahir: attributed to the first century sage, Rabbi Nehuniah ben HaKana and his school, this text deals with important kabbalistic concepts like the 10 sefirot, the mysteries of the Hebrew alphabet, and other significant themes. It is often quoted in other kabbalistic texts.

Zohar: the primary work of Kabbalah, and an important source text for most kabbalistic thought. Its authorship is attributed to the second century sage, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, but it’s important to note, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai didn’t write the Zohar per se. Rather, his students compiled his teachings, which were later arranged by subsequent generations.

“The truth is that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai did not write these words of the Zohar in a book and he did not arrange the words according to the sequence of the Torah readings as we have it today … The Zohar was written several generations after Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai with what was written and passed down in his name and that of the rest of his contemporary colleagues and students. Even this was with a great many additions being made to it by the later generations after it was put into writing and given out to be copied … We find [from] the writings of the Arizal that [he states that] several sections are not from the Zohar at all. The truth is that one who looks properly who is experienced and expert in it, will understand and figure out the difference between what comes from Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, his colleagues and students, and what was added by the later generations … The arrangement of the holy Zohar according to the sequence of Torah readings was done in the [much later] time of the Gaonim13 as the Kabbilists wrote.”14

The Zohar was first published in the late 13th century by Rabbi Moses de Leon from Spain.

The Torah commentary of Rabbi Moses Nachmonides: this work, completed near the end of his life (he died in 1270), is a commentary on the verses of the Torah, and often draws from Kabbalah to explain various concepts and ideas.

Pardes Rimonim: written by Rabbi Moses Cordovero from Tzaft in 1548, this work—along with the author’s other works—organizes and helps systematize many disparate kabbalistic ideas.

The writings of the Arizal: Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534-1572)—known as “the Godly Rabbi Isaac of blessed memory (האריז׳ל)”—is considered one of the most important and influential kabbalistic thinkers. His teachings were compiled and published by his students, most notably Rabbi Chaim Vital and Rabbi Israel Sarug.

Kabbalah deals with myriad ideas and concepts, the most well-known being the 10 Sefirot, the “Breaking of the Vessels,” and the Partzufim.

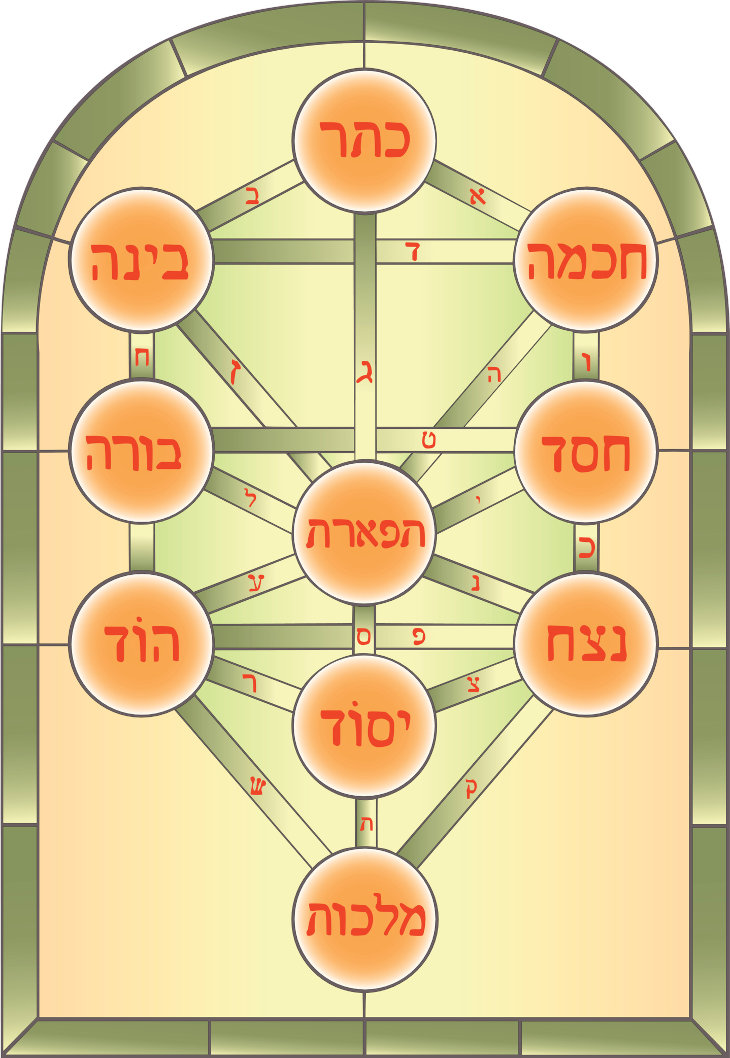

The 10 Sefirot are the basic building blocks of kabbalistic terminology. Their names derive from Proverbs 3:19-20, “With wisdom (חכמה), God established the earth, and with understanding (תבונה), He established the heavens, and with His knowledge (דעת), the depths were broken up;” and Chronicles I 29:11, “Yours God are the greatness (גדולה), the strength (גבורה), the beauty (תפארת), the victory (נצח), and the splendor (הוד), for all (כל) in heaven and in earth; yours God is the kingdom (ממלכה).”15 Most systems, however, use another level, “Crown (כתר),” as the top Sefirah, and don’t include “Knowledge (דעת).”16

The 10 Sefirot are:

When Keter is excluded, and Daat (דעת), knowledge, is included instead, it’s listed between Binah and Chesed.

The “Breaking of the Vessels” is a complex and detailed concept that describes the intricacies of the creative process. It’s analogous to a seed that, after it’s planted, rots, but is then reconstituted and rearranged, and grows into a flourishing new tree.17 That idea is used to explain many other creative, or generative, situations as well.

Partzufim, or in the singular, Partzuf (Hebrew for Face/פרצוף), refers to the idea of the reconstitution of separate building blocks into a new entity, but that what emerges from that reconstitution is a reality that is greater than the sum of its parts.

For example, a face is the combination of diverse elements like a nose, eyes, ears, and a mouth. Each of these elements can be understood and discussed as an individual entity, but when you combine them together, they become something new, a face. You wouldn’t look at a nose and think, “face,” yet a nose is integral to the face. It’s the combination of these disparate elements that creates a new entity, which, in essence, is something greater than the total of its individual components.18

The most common kabbalistic practice is the consistent and regular study of kabbalistic texts. Many of the most important works have been edited, annotated, and corrected, and new editions have been published based on scholarly research that started with analyzing centuries-old handwritten manuscripts. Many important kabbalistic works have been translated into modern Hebrew, English, and other languages as well.

The most common practical application of kabbalistic ideas is as they’re applied to the daily prayer service. That application ranges from having a deeper, or more meaningful, understanding of the structure and order of prayer; to having greater intention, or focus, while engaged in prayer; to the usage of divine names and unifications; to, as per the Hasidic tradition, embracing the deeper meditative aspects of prayer.

Kabbalah wrestles with some of the Torah’s deepest mysteries, and for the person unfamiliar with the basics of Torah study, it can seem confusing and overwhelming. However, many of the important principles of Kabbalah—especially as they relate to things like comprehending God’s oneness, and the other foundations of Jewish belief—are accessible to nearly everyone via the writings of people like Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (1707-1746), the early Hasidic masters, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan (1934-1983), and others.

Kabbalah, from the Hebrew word, mekabel (מקבל), is received knowledge or wisdom. It is the study of how to understand and relate to God, and is vital to comprehending many of the Torah’s commandments. Kabbalah isn’t a single book, it’s an area of study, and thousands of texts deal with kabbalistic concepts, some of those main ideas being: the 10 Sefirot, the “Breaking of the Vessels,” and the Partzufim. Kabbalah is practiced via study and prayer, and while its deepest secrets are difficult to comprehend without a rigorous Torah education, many of its important ideas have been made accessible to the common man.

Kabbalah isn’t a single book. Kabbalah is an area of study. Thousands of texts deal with kabbalistic ideas, and most of those have been written or compiled over the last 2,000 years. The most significant kabbalistic texts include the Sefer Yetzirah, the Bahir, the Zohar, the Torah commentary of Rabbi Moses Nachmonides, Pardes Rimonim, and the writings of the Arizal as compiled by his students.

The red thread (roiteh bendel in Yiddish) is a “Jewish” practice that isn’t very Jewish. There is no known early source that mentions or condones it, and if it has any kabbalistic powers, no work on Kabbalah makes any mention of it.

Thank you so much for this introduction to the meaning of Kabbalah and its writings. So many of us will benefit from this most important article. Steve Finer

In modern Hebrew a "מקובל" is someone (or something) accepted or acceptable. The root for "receive" in Hebrew is קבל and one who receives is a "מקבל".

And that is why you can't just pickiup any book and read about it.

It has to be from an authorative source, and anyone who really knows is stuff will not share it it with anyone unless he knows that the one he is teaching is already a fully-practising Orthodox Jew who is already well versed in the Revealed Torah.

True books on Kabbalah, like the Zohar, are writteen in the same style as the Gemara - very brief note-form, and you have to be taught how to fill in the missing parts.

Kabbalah is NOT central to the practice or understanding of Judaism. H" (blessed is He) and His Torah are central to Judaism. Witchcraft (chiromancy and astrology) and gnosticism are forbidden by H" in Torah.

The Kabbalah Yochanan is refering to is the "pop" stuff they teach in Holywood and what they read in "pop" books.and what the Christians dabbled in in the Middle Ages.

Chassiduss is some aspects of Kabbalah, made easy for the layman.

If Yochana wants to get better informed about real Kabbalah, he should have a chat with a senior Orthodox Jewish Rabbi.

That's better stated

Loshon Kodesh is the programing language of the world's existence.

A computer runs on binary code - 0 or 1.

Computer Programs are written in English but do not make literary sense

The world runs on the 22-letters of the aleph-bet.

The Torah can be read in 2 levels.

A literary text of infinite depth of meaning - the Revealed Torah

And as a programing language by Mekubalim - the Nister - Hidden Torah.

So, when you read, write or even think in Loshon Kodesh, you are creating worlds. Praying in Loshon Kodesh is okay, even without understanding the words. The words do the job.

In early times, Jews avoided writing in the characters of Loshon Kodesh and used an alternative, Loshon Ivri or Phenoecian. Later, we use alternatives for general speaking, Aramaic, Arabic, Ladinino, Yiddish.

That's study of the Kabbalah is very interesting I read a book on it years ago and I forgotten a lot of it that is really neat. I'm not Jewish but I love the Jews shalom shalom

Kabbalah is NOT central to the practice or understanding of Judaism. H" (blessed is He) and His Torah are central to Judaism. Kabbalah is not even Judaism

It is certainly part of Judaism, but the true study of Kabbalah is not simple and not for everyone. Once it was required both that a person be over a certain age (I think 40) and have first a thorough grounding in the "revealed" wisdom - Torah & Oral Law.

Unfortunately today some scraps of mostly distorted concepts have fallen into the hands of charlatans who use them for personal promotion and profit. That being so, it becomes necessary to counter false ideas with a smattering of the true ones.