Identifying as a Jew

Identifying as a Jew

8 min read

The city, recently designated by UNESCO as a world heritage site, was a place of significant Jewish scholarship and horrific antisemitic violence.

UNESCO, the United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, recently designated three buildings in Erfurt’s city center UNESCO world heritage sites. “Located in the medieval historic center of Erfurt, the capital of Thuringia, the property comprises three monuments: the Old Synagogue, the Mikveh, and the Stone House,” UNESCO declared. “They illustrate the life of the local Jewish community and its coexistence with a Christian majority in Central Europe during the Middle Ages….”

The Old Synagogue, Western façade, courtesy Unesco

The Old Synagogue, Western façade, courtesy Unesco

“Coexisted” might be overstating it. For generations, Jews in Erfurt did indeed live and work alongside their Christian neighbors, but waves of prejudice and violence disrupted Erfurt’s Jewish community time and again. Despite the intense hatred that was too often directed against them, Erfurt’s Jews flourished, producing vibrant Jewish communities and scholars whose words are still read today.

Jews began settling in Erfurt in the 800s, according to the oldest dates in the town’s Jewish cemetery. By the late 1000s, the Jewish community boasted a synagogue and mikveh (ritual bath). Tax and census records show a thriving Jewish community situation next to the Town Hall in Erfurt’s center. Municipal records show that many Jews worked in banking (money lending being one of the few occupations which Jews were allowed to pursue in Medieval Europe) and traded goods across Europe.

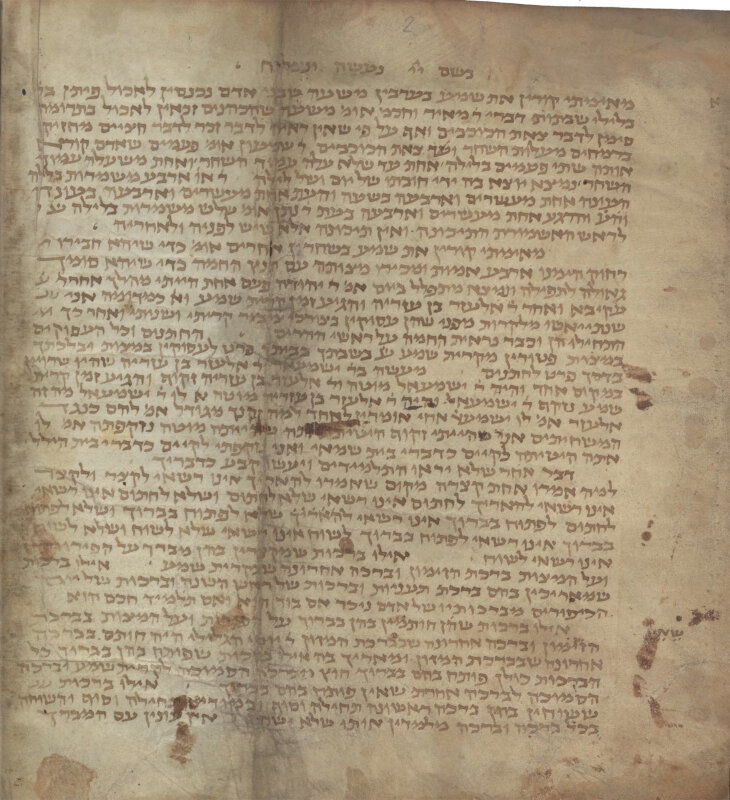

Erfurt became a center of Jewish scholarship, with Jews from throughout the area traveling to study with Erfurt’s renown rabbis. In fact, the oldest manuscript in existence of the Tosefta, a set of Medieval commentaries that are still studied today, was written by Erfurt scholars during the Middle Ages.

The Tosefta, Part of the Erfurt Collection

The Tosefta, Part of the Erfurt Collection

Many of the records we have from this period speak both of the dynamism of Erfurt’s Jews, as well as untold hardship and danger they endured. Local Christians repeatedly turned on Jews in their midst. Across Germanic lands, Jews lived at the mercy of local noblemen and local priests, who could choose to protect Jewish populations in their midst or not, often in return for large bribes. It was a precarious time.

One of the worst spasms of violence occurred on July 26, 1221, when local Christians on their way to fight in the Fifth Crusade massacred Jews in Erfurt on their way to the Middle East. Accounts vary: between 26 and 86 Jews were murdered in Erfurt on that day, and unknown numbers injured. For years, Erfurt’s Jews observed a fast and day of mourning to commemorate the victims.

In archeology, a “horde” refers to items that were buried, often because the owner feared he or she would be robbed or attacked, and hoped to be able to come back and receive their possessions at a later, safer time. In 1998, researchers discovered the “Erfurt Horde” under the wall of a stone cellar in Erfurt’s old Jewish quarter. They estimate it was buried sometime in the 1100s, during one of the periodic spasms of violence that threatened Erfurt’s Jews.

Erfurt Horde excavation site, Courtesy Unesco

Erfurt Horde excavation site, Courtesy Unesco

It likely contains the wealth of several Jewish families: over 3,000 silver coins, 14 silver ingots, 600 items of jewelry, silver kiddush cups, a cosmetic case, and some items of clothing. Two of the kiddush cups portray unusual carvings of Aesop’s fables (the Fox and the Eagle on one cup and the Fox and the Raven on another) around their sides. A woman’s gold wedding ring is shaped to look like the ancient Temple in Jerusalem and says “Mazel Tov” on the sides. Pictures of other similar rings survive from the Middle Ages, but most were melted down to form new jewelry; the Erfurt ring is one of the few that exists today.

The Erfurt ring

The Erfurt ring

Hundreds of years of the “coexistence” UNESCO is commemorating came to an end in 1348, when simmering tensions boiled over in Erfurt. The Black Death had been sickening people in the area for over 30 years. As elsewhere in Europe, Jews were often blamed for spreading the disease. Locals accused Jews of poisoning Christian wells, and these baseless claims were encouraged by local Dominican priests and the chief of Erfurt’s political council. Many local Christians were in debt to Jewish money lenders; if the Jews were out of the picture, these debts could be forgiven.

Fear and suspicion led to violence. On March 21, 1348, mobs attacked Erfurt’s Jewish quarter, killing hundreds. Estimates of the numbers of dead range from 900 to over 3,000. Erfurt’s city council seized Jewish property, including 800 Marks (the currency of the day), furniture, and household items. Erfurt’s synagogue was turned into a storehouse.

Jews returned to Erfurt scarcely a year later. This time, “coexistence” was even more lacking. In time, thousands of Jews moved to the city, expanding the Jewish areas beyond their previous borders and building a new synagogue. Yet as the Renaissance dawned, Erfurt’s anti-Jewish sentiment became increasingly codified into edicts. Jews in the city were ordered to wear special long robes, boots and hats to distinguish themselves. Jewish women were prohibited from wearing jewelry and fashionable waistbands. Erfurt’s Jews were forced to pay exorbitant taxes merely for the privilege of living in the town.

Erfurt treasures, Courtesy Unesco

Erfurt treasures, Courtesy Unesco

As time went on, these restrictions and the Jews’ tax burden increased. They had to pay an enormous one-off special tax in 1380. In 1391, King Wenceslaus of Bohemia ordered that all debts to Jews were erased, wiping out Jewish banking businesses. Ruinous special taxes were leveled on the Jews with increasing frequency. Jews were given permission to live in Erfurt only for set periods; every five or ten years, they had to seek permission to remain living in the town.

Despite the intense prejudice against them, Erfurt’s Jews thrived. Erfurt became noted for its Jewish scholarship and some of the Middle Ages greatest Jewish sages and rabbis lived and taught there.

Excavations in 2007 of the medieval Mikveh in Erfurt uncovered this portrait of David.

Excavations in 2007 of the medieval Mikveh in Erfurt uncovered this portrait of David.

Despite Erfurt’s important role in European Jewry, antisemitism prevailed in the end. Hatred for Jews reached a head in the early 1450s when the Italian priest (and patron saint of military chaplains and jurists today) John of Capistrano visited Erfurt and surrounding towns, preaching hatred of Jews. The mood in Erfurt and surrounding towns darkened considerably. In 1450, Erfurt’s city council revoked Jews’ right to live in the city. For the next 254 years, no Jew was allowed to reside in Erfurt. The town’s synagogue (the Old Synagogue in UNESCO’s declaration) was turned into an armory and the Jewish cemetery was largely destroyed.

Jews were allowed back into Erfurt after the Napoleonic Wars, when Erfurt and the surrounding areas became a French territory. The first Jew of that era to move into Erfurt was a man named David Solomon Unger, in 1804. He was soon joined by many others. The new Erfurt Jewish community built a grand new place of worship known as the Great Synagogue.

In 1932, census records show 1,290 Jews living in Erfurt. Jewish-owned local businesses including wool, clothing manufacturing, shoemaking and beer making, and contributed greatly to the prosperity of the town. Three Jews sat on Erfurt’s city council in the 1920s and the city boasted many Jewish charitable organizations.

Virtual reconstruction of the Great Synagogue of Erfurt, which was consecrated in 1884 and destroyed by the National Socialists in 1938

Virtual reconstruction of the Great Synagogue of Erfurt, which was consecrated in 1884 and destroyed by the National Socialists in 1938

With the election of Hitler in 1933, many Jews fled Erfurt and other German towns. Those who remained were present to watch locals destroy and burn the town synagogue on Kristallnacht, the night of November 9th and 10th, 1938. They attacked hundreds of Jews. Starting in September 1941, all the Jews who still lived in Erfurt were deported to Nazi death camps.

The Stone House, west façade, with neighboring buildings, courtesy Unesco

The Stone House, west façade, with neighboring buildings, courtesy Unesco

After the Holocaust, virtually no Jews remained in Germany. Those few Jewish survivors who found themselves alive largely left, bound for the Land of Israel, America, or elsewhere. Yet Erfurt was somehow different. This city, once home to so many persecuted Jews, which nevertheless saw rebirth after Jewish rebirth through the ages, once again became a home to Jews. In 1946, 120 Jewish Holocaust survivors moved to Erfurt, establishing what soon became the largest Jewish community in East Germany after Berlin. A “New Synagogue” was built in 1952 on the site of the Nazi-destroyed Great Synagogue.

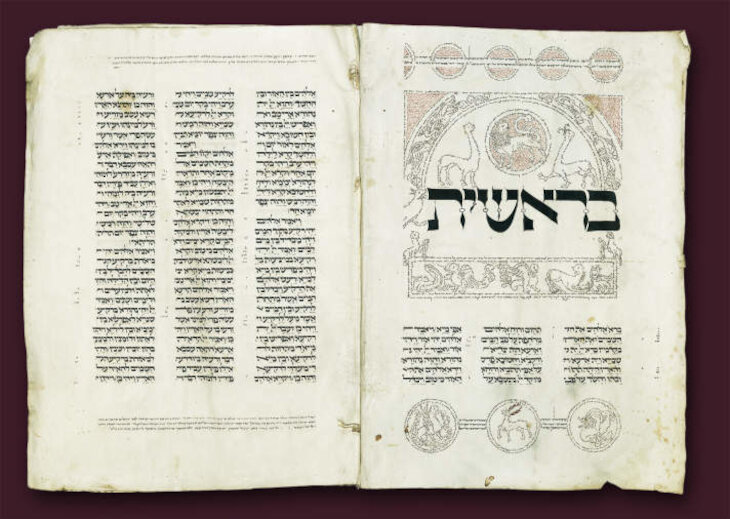

A Bible from the Erfurt Collection

A Bible from the Erfurt Collection

After 1990, Jews from the former Soviet Union poured into Germany. The German state of Thuringia, where Erfurt is located, has approximately 800 members. The city’s New Synagogue is the heart of Jewish life in the area, once again giving Jews in Erfurt a place to pour out their hearts in prayer.

Now that UNESCO has recognized Erfurt’s long Jewish history as a protected site, local Jews hope that tourists will visit their town, learning more about both Erfurt’s long Jewish history, and its thriving Jewish life today.

Fascinating though I never understood the reason to want to to live in Germany. Thanks for this article.

Why would any Jew want to live in Germany after all the war crimes that the Germans have committed?

Early 1973 my wife I I made Aliyah and left after my miluim late 1975 due to the economic crisis following the Yom Kippur War. We visited London with my sister wanting to return to Israel having been a kibbutznik and enquired about returning residents help. The Shaliakh only wanted to know about my wife and me. He finally said the Israel did not want immigrants from the UK or America, only the Russians who are the life blood of Israel.

Being an Anglo at the time was virtually a curse. Conditions were very bleak and evidence that only those from the Soviet Union warranted any help.

Hopefully it's different today. In my heart I am Israeli still and mange to visit as often as I can manage it financially.

Am Yisrael Khai

Witnessing the surge of Jew hate around the world including the USA, Canada UK, Australia and Europe, bears forecasting the end of Jews in Blood soaked Europe.

I really believe that in 50 years from now, Europe will be more or less Jew free,

Sadly my forecast many years ago that because of Mosl;ems putting into Europe and claiming their areas as off limits to the police etc will hasten the Jew hate and ant-Semitism that although in evidence would again erupt into violence against Jews.

Even in north American Australia etc it is difficult to ignore,

At the age of 82, I will finish my days in Britain unfortunately. Young Jews need to leave and set up some in our ancestral homeland.

Why would any Jew choose to live in this blood soaked country

As we were looking for where my husband's great-grandfather came from, we found a man by the same name who was listed as being born in Erfurt. We don't know if they are one and the same man, but it's intreaguing to think about after reading this article.

I never heard of the city of Erfurt. Thank you for posting, it was interesting.

Teri

Atlas Biomechanics

Its my hometown and very very beautiful. In the Communist time IT was nearly destroyed, but after the wall came down all the old jewish Sites From the medieval time we're discovered. In highschool i took part in an History Project about jewish life in Erfurt and spent weeks in archives and libraries studiing about jewish History in the City overnight decades. IT opened my Horizon and i am Sure not many people have a knowledge about all of this. So thanks a Lot about this Article!