Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

8 min read

How America's favorite author responded to accusations of being a Jew.

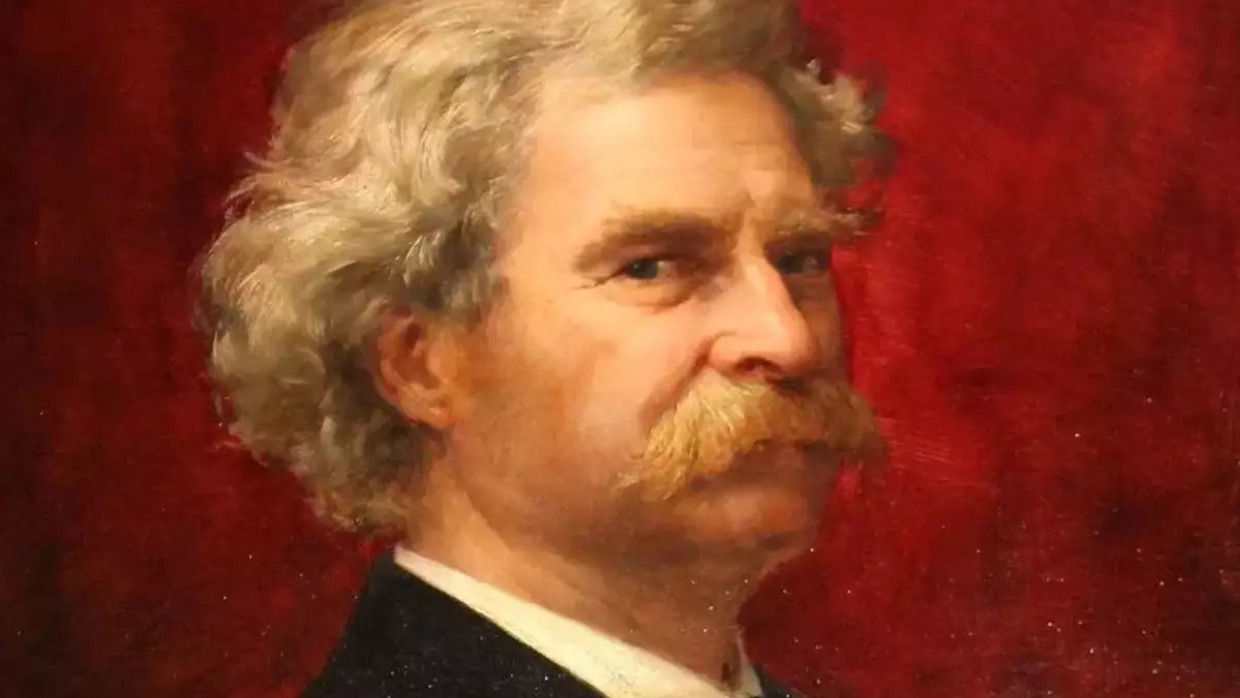

Together with their daughters Clara and Jean, Samuel and Olivia Clemens arrived at Vienna’s Hotel Metropol on September 28, 1897. Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was short on cash and planned to earn money through lectures and travel writing, while Clara, an aspiring singer, hoped to study music with the pianist Theodor Leschetizky in one of Europe’s most cosmopolitan cities. Expecting a pleasant and unremarkable stay in the imperial capital, the family had no inkling of the maelstrom of antisemitism that awaited them.

After Austro-Hungarian Jews were emancipated in 1867, giving them civil rights and freedom of movement, tens of thousands of Jews moved to Vienna from the ghettos of central and eastern Europe. By the time Twain arrived with his family, Vienna was home to 145,000 upwardly mobile Jews, many of whom occupied prominent positions of influence.

The golden era of Viennese Jewry, however, would be short lived. As Clara Clemens would later write, “In every walk of life there were large numbers of successful Jews, so much so, that one frequently heard the complaint: ‘Everything in this city is owned by the Jews – newspapers, banks, high professional offices, and all the successful shops’” (My Father, Mark Twain, 203).

Twain’s visit to Vienna coincided with a new wave of antisemitism in the Austro-Hungarian empire. A few months earlier, the infamous antisemite Karl Lueger was elected mayor of Vienna, lending official respectability to a form of blatant and public antisemitism that previously had simmered beneath the surface of respectable society. Hitler would later describe Lueger as “the greatest German mayor of all time” in his infamous autobiography Mein Kampf. In those days, Vienna was, in the words of journalist Carl Dolmetsch, a “cesspool of antisemitism.” Meanwhile, the infamous Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish French army captain was falsely accused of spying for Germany, reverberated throughout Europe, triggering a wave of antisemitic riots in over twenty French cities in early 1898.

The great author’s arrival was celebrated in all of Vienna’s newspapers, and Twain was immediately besieged with requests for interviews and invitations to lecture. Aristocrats, diplomats, dramatists and journalists all vied for the great man’s attention. Innocently, Twain immediately granted interviews to Sigmund Schlesinger, Eduard Potzl, Ferdinand Gross and Vincenz Chiavacci, all of whom happened to be Jewish writers. The non-Jewish writers of Vienna had been scooped – and they soon made their jealousy and resentment known.

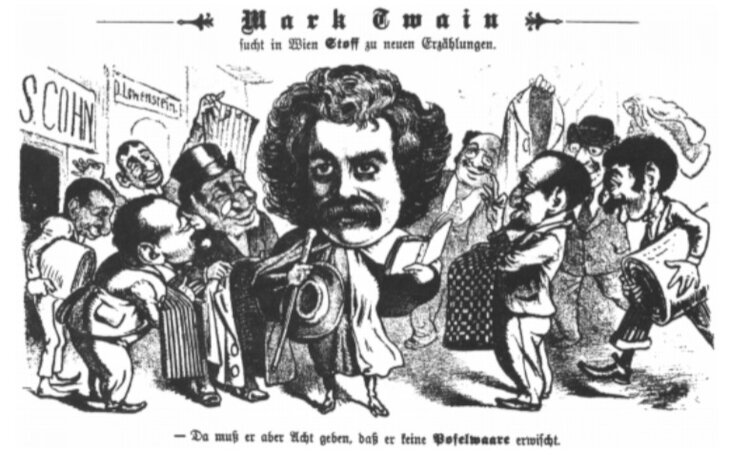

The first attack on Twain, published in the antisemitic newspaper Kikeriki, was a cartoon depicting Twain surrounded by caricatures of Jewish storeowners hawking clothing and bolts of cloth to him in front of stores with obviously Jewish names. The caption beneath the cartoon read: “Mark Twain is looking for new material for stories in Vienna, but he better watch out that he doesn’t get shoddy goods.”

The cartoon, however, was just the beginning. Twain soon found himself targeted not only for associating with Jews, but for being a Jew himself! In February, 1898, Kikeriki once again attacked the American writer, suggesting that he adopted his pen name in order to hide his Jewish identity. Austrian Catholics never used names from the Hebrew Bible, and so “Samuel Langhorne” struck Viennese antisemites as a Jewish name. The “slur” soon caught on, and before long newspapers throughout Vienna were noting that Twain’s nose was large and crooked and referring to him as “der Jude Mark Twain” or “der jüdische amerikanische Humorist.” Antisemitism was no longer a theoretical issue for Twain, but how the American icon would respond was an open question.

Unlike many of the writers of his generation, Twain had a soft spot for the Jews. Though he mercilessly poked fun at Mexicans, Native Americans and the Irish, his writings contain relatively few jokes about Jews. In his best-selling first book, The Innocents Abroad – a humorous chronicle of his trip to the Holy Land in 1867 – Twain was far more biting in his criticism of Christianity that he was of Judaism. He was pleased by the popularity of his books in Yiddish translation, and upon hearing that the Yiddish writer Sholem Alechem was called the “Jewish Mark Twain,” Twain said, “Please tell him that I’m the American Sholem Aleichem.”

Unsurprisingly, Twain’s personal experience of antisemitism heightened his awareness of the Jewish people’s tenuous status in Viennese society. Describing a crisis in the Austrian Parliament for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Twain mockingly wrote of the Austrian parliamentarians: “They are religious men, they are earnest, sincere, devoted, and they hate the Jews.” Recounting the rioting that followed the crisis, he noted that “in other Bohemian towns there was rioting – in some cases the Germans being the rioters, in others the Czechs – and in all cases the Jew had to roast, no matter which side he was on” (Stirring Times in Austria, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1898).

Twain’s unpleasant experiences also drew him to Theodor Herzl. Covering the Dreyfus trial as a journalist, Herzl was deeply shocked by the virulent antisemitism that broke out in France and became convinced that Jews must emigrate and establish their own, independent nation. He soon published The Jewish State and convened the First Zionist Congress, launching the Zionist movement that would forever alter the destiny of the Jewish people.

Impressed by Herzl and his vision, Twain expressed his support for Zionism with characteristic irony. “If that concentration [in Palestine] of the cunningest brains in the world were going to be made on a free country (bar Scotland), I think it would be politic to stop it… It will not be well to let that [Jewish] race find out its strength. If the horses knew theirs, we should not ride anymore.”

Twain authored his most comprehensive and well-known response to antisemitism in his essay “Concerning the Jews,” published in Harper’s in 1898. Very proud of the essay, he wrote to a friend that “The Jew article is my gem of the ocean. I have taken a world of pleasure in writing it and doctoring it and polishing it and fussing at it. Neither Jew nor Christian will approve of it, but… I really believe that I am the only one in the world who is equipped to write upon the subject without prejudice.”

As Twain had suspected it would, the essay met with a mixed reception, and for good reason. Its conclusion – a stirring ode to the immortality of the Jewish people – is regularly cited with pride by the Jewish community to this day. “The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts, no slowing of his energies, no dulling of his alert and aggressive mind. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?”

Unfortunately, Concerning the Jews is a philosemitic essay that is itself marred by antisemitic generalizations. Among other cringeworthy comments, Twain describes the Jew as a “money-getter” with “a reputation for various small forms of cheating.” Ironically, in an essay dedicated to defending the Jews, Twain carelessly promoted the ancient canard of the Jew’s obsession with money. Some of these paragraphs would later be used by American pro-Nazi groups in the 1930s to foment hatred against the American Jewish community. The London Jewish Chronicle spoke for many Jews when it commented, “Of all such advocates, we can but say ‘Heaven save us from our friends.’”

Yet Twain’s analysis of the “Jewish problem” – the essential aloneness of the Jewish people – cuts to the core of the Jewish experience. “By his make and ways he is substantially a foreigner wherever he may be, and even the angels dislike a foreigner… Nearly all of us have an antipathy to a stranger, even of our own nationality.” With these words, Twain echoed another gentile, Balaam the prophet, who said at the very dawn of Jewish history that the nation of Israel is “a people that dwells alone, not reckoned among the nations” (Numbers, 23:9).

The Clemens

The Clemens

The great Baltimorean journalist, H.L. Mencken, would later reiterate Twain’s assessment: “[The Jewish problem will continue] until the Jews learn to go from Saturday to Friday without recalling once that they are Jews, just as the rest of us put in whole weeks without recalling that we are Aryans, or Chinamen, or members of Blood Group number 4, or what not… The sharp, unyielding separateness of the Jews, marks them off as strangers everywhere… The average Jew is Jewish before he is a man, and presses the fact home with relentless lack of tact. This habit, I suspect, is one of the chief causes of Jewish unpopularity, even among those who are not rationally to be called antisemitic.”

We can say with confidence that Twain certainly meant well. As Cynthia Ozick writes, “We can believe Mark Twain… when he avers that he makes ‘no uncourteous reference’ to Jews in his books ‘because the disposition is lacking.’” But for all of his good intentions, Twain never grasped that the Jewish people’s unique aloneness is not only the root of its suffering, but also the secret to its miraculous survival and success. As painful as it may sometimes be, the Jewish People understand that aloneness is not a curse, but a blessing.

Twain also delivered this insightful remark: "Like many Christians, I was brought up to dislike Jews. However, if I had these thoughts in my head, I never had them in my heart.".

A very enlightning article. I have always enjoyed Mark Twain sense of humor and his sense of a story. Learning of his connnection to the Jewish people, casts him in a whole new light. Thank you!!