Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

8 min read

Jewish principles for change have been corroborated by recent discoveries in brain science.

Can people really change?

Throughout centuries when ancient cultures believed in fatalism and modern cultures believed that who you are is determined by genes and environment, Judaism has propounded the radical notion that human beings have free will in the moral sphere; they can change if they want to.

I am an example of such change on the macro level. I went from being a radical leftist member of S.D.S. and a monastic member of a Hindu ashram for 15 years to being an Orthodox Jew living in Jerusalem and supporting the Zionist parties that my former leftist friends demonize.

I've changed on the macro level, but could I go from being competitive to cooperative, hellbent to helpful, selfish to generous?

But what about change on the micro level? Could I go from being a short-tempered, anger-prone person to being a calm, restrained person who would rather befriend her opponent than decimate him? Could I go from being competitive to cooperative, from being hellbent to helpful, from being selfish to generous, from being cantankerous to kind?

Come Yom Kippur, it is those changes that count.

The good news is that Judaism insists that you CAN change. The bad news is that it takes a long period of consistent, small efforts.

Amazingly, both these principles have been corroborated by the latest discoveries in brain science. Neuroscience has discovered that the brain is “plastic,” which means that it changes every day, in fact with every thought. Neuroplasticity is the term that refers to the ability of the brain to change continuously throughout an individual's life. Norman Doidge, M.D., a neuroscientist at Columbia University, asserts in his book, The Brain that Changes Itself, that brain plasticity exists from the cradle to the grave.

This is the scientific corroboration of the ability of a human being to do teshuva, to change one's life around.

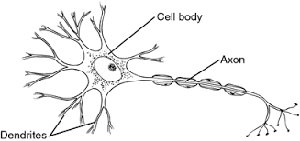

Thoughts take place in the neurons of our brain. The brain consists of 100 billion neurons. A neuron consists of three parts: the dendrites, which look like treelike branches, the cell body, and the axon, a cable that carries electrical impulses toward the dendrites of neighboring neurons. Every time you repeat a thought, the dendrites of the neurons associated with that thought grow. When you stop thinking a habitual thought, the dendrites shrivel up and disappear.

“Practicing a new skill, under the right conditions,” writes Dr. Doidge, “can change hundreds of millions and possibly billions of the connections between the nerve cells in our brain maps.”

“Practicing a new skill, under the right conditions,” writes Dr. Doidge, “can change hundreds of millions and possibly billions of the connections between the nerve cells in our brain maps.”

Let’s say that during this season of teshuva you decide that you are going to stop hurting other people with sharp, insulting, or sarcastic words. This ingrained bad habit of yours is ensconced in a well-worn path in your brain map. Someone says something that ticks you off, and you automatically reply with a nasty retort. Can you really change?

According to Dr. Doidge, one of the key principles of neuroplasticity is: “Use it or lose it.” In grade school we all knew the multiplication tables. Years later, if we pull out a calculator every time we have to multiply numbers, the multiplication tables can actually disappear from our brains. In my twenties, I worked in an orphanage in Calcutta; I spoke, read, and wrote Bengali. Recently I passed a group of Bengali tourists in my neighborhood in the Old City of Jerusalem. I wanted to impress them with my knowledge of their language, but all I could remember was a feeble, “Namaskar.”

“Use it or lose it” actually explains our ability to do teshuva and change. According to the Mussar Masters of the last two centuries, if you want to stop hurting other people with words, you must devise a program where, starting with just 15 minutes a day, you actively refrain from saying anything hurtful. After a couple of weeks, you extend the period to 30 minutes, then gradually to 45 minutes, then to an hour. You can use your cellphone alarm to remind you when your “no hurtful words” period starts and when it ends.

That you can, by an act of will, resist a lifelong habit even once out of every three occasions is significant. A batting average of .333 makes you a champion.

What is going on in your brain during that period? Every time you refrain from treading the well-worn path of hurtful words in your brain, the dendrites of the neurons associated with that path shrink. “Use it or lose it.” Eventually as your designated time period to be vigilant expands, your brain map actually changes. Teshuva occurs one thought at a time.

You may think that refraining from hurtful words once a day is worthless if you make cutting remarks two times later in the day. But every thought has an effect of either growing or shrinking the dendrites. That you can, by an act of will, resist a lifelong habit even once out of every three occasions is significant. A batting average of .333 makes you a champion.

This leads us to another Mussar method corroborated by neuroscience. The Mussar Masters teach the importance of making a chart. Every time you do the exercise you have chosen, you give yourself a check on the chart. When you have earned a certain number of checks (decided by you), you go out and “reward the body.” This can mean chocolate, a dinner in a gourmet restaurant, a new garment, a massage, a new high-tech gadget, or something else on which you would not normally spend that much money. Rewarding yourself solidifies the change.

For example, let’s say you have a co-worker who presses your buttons and your default response is to answer with a sarcastic, cutting remark. Now you are doing teshuva. You set your cellphone alarm. From 10:00 to 10:15 AM, you will not let any hurtful words escape your lips. You succeed, and at 10:15 you give yourself a check on your chart, feeling like a mini-hero. When you get ten checks, you go to the store you pass every day on your way to work and buy the item in the window that you’ve been wanting but didn’t buy because you felt like it was an indulgence. You look at it and glow.

I have personally experienced how the method of small, daily exercises can lead to fundamental behavior changes over time. The only part of the method that perplexed me was “rewarding the body.” Here I was engaged in an exalted spiritual practice and I when I succeeded, I should go out and buy myself a box of Belgian chocolates?

Only when I read The Brain that Changes Itself did I realize the genius of the practice. Dr. Norman Doidge explains that a second basic principle of neuroplasticity is: “Neurons that fire together wire together.” Dr. Doidge tells about experiments done with children with major language processing problems. They worked on a computer program to actually change their brains. When the child achieved a goal, something funny would happen: the character in the animation would eat the answer, get a funny look on his face, etc. Dr. Doidge writes: “This reward is a crucial feature of the program, because each time the child is rewarded, his brain secretes such neurotransmitters as dopamine and acetylcholine, which help consolidate the map changes he has just made. (Dopamine reinforces the reward, and acetylcholine helps the brain ‘tune in’ and sharpen memories.)”

Whereas it used to make you feel good to make a wisecrack at your co-worker’s expense, now you feel good by refraining from the wisecrack.

In other words, if you are about to make a cutting remark to your co-worker and you stop yourself, you give yourself a check on the chart. The brain registers this as a pat on the back and secretes neurotransmitters such as dopamine and acetylcholine. You feel good about what you just did (refraining from hurtful words), and “neurons that fire together wire together.” Next time you are about to make a hurtful quip, you will associate the act of refraining with pleasure. Whereas it used to make you feel good to make a wisecrack at your co-worker’s expense, now you feel good by refraining from the wisecrack. After you get, say, twenty checks, you go out and buy yourself that new gadget you have earned. Every time you use the new gadget, you feel happy.

“Neurons that fire together wire together.” You have rewired your brain. Now you associate refraining from hurtful words with happiness. This is lasting teshuva.

It’s too close to Yom Kippur for you to make any significant changes in your brain or your behavior. But you can decide the one or two changes you want to make in your life and start with the program outlined above: specific, small steps on a daily basis, charting, and rewarding the body. It’s important to join a group of similarly aspiring Jews in one of the many local or online programs. The support of an ongoing group is essential for lasting change. Commit to sticking with the program at least till Chanukah. On Yom Kippur, tell God: “I’ve just started to develop this muscle, but I did join the gym. And I’m going to do my spiritual workout every day.” And mean it.

Sara Yoheved Rigler gives a weekly webinar, the Kesher Wife Club, for women who want to work on themselves spiritually through their marriages. For more information, see www.sararigler.com.