Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

Debunking Viral Claim About the Talmud and Minors

18 min read

When most countries turned away desperate refugees fleeing Nazi terror, one unlikely Caribbean island provided Jews with a safe refuge.

When the Nazis came to power, they sought to make their country judenrein – free of Jews. At first, their plans did not involve mass murder. They would have happily allowed the Jews to emigrate to any country in the world that was willing to take them in. Unfortunately, most Jews had nowhere to go.

In 1938, after the Anschluss – the German annexation of Austria – delegates from 32 countries met at the Evian Conference in France to discuss the issue of Jewish refugees. Each delegate expressed sympathy for the refugees and then gave excuses for why their country would be unable to take them in.

Out of these 32 countries, only one agreed to accept desperate Jewish refugees. That country was the Dominican Republic, located on an island in the Caribbean Sea.

The Evian Conference was initiated by U.S. President Roosevelt in response to criticism of the U.S. immigration quotas by American Jewish philanthropic organizations, which sounded the alarm at the distressing news coming out of Germany and Austria. When the Dominican Republic offered to accept up to 100,000 refugees, Roosevelt seized the opportunity to participate in addressing the refugee crisis without increasing U.S. quotas. The United States became heavily involved in the proposed resettlement of European Jews in the Dominican Republic.

Jewish refugees work in the field in Sosua, Dominican Republic. Unknown author, between 1941 and 1946. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Jewish refugees work in the field in Sosua, Dominican Republic. Unknown author, between 1941 and 1946. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

American philanthropists also stepped in. In 1939, the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) founded the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA) to manage the project, providing initial investment and financial assistance to Jewish immigrants to the Dominican Republic. James Rosenberg, an American-born lawyer, was elected president, and Joseph Rosen, a Russian-born agronomist, was elected vice-president. Both Rosenberg and Rosen had previous experience with developing a Jewish agricultural settlement in Russia. They believed they could succeed in building an agricultural settlement in the Dominican Republic.

In 1940, DORSA and the Dominican Republic representatives signed a contract. The Dominican Republic committed to ensuring full civil rights and religious freedom for the Jewish refugees. DORSA, on its part, committed to funding the new settlement and ensuring that the refugees did not become a financial burden on the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican leader, General Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina, presented DORSA with a gift of about 26,000 acres of land on the northern coast of the Dominican Republic. This land became Sosua, the only town in the world settled by Jews fleeing the Holocaust.

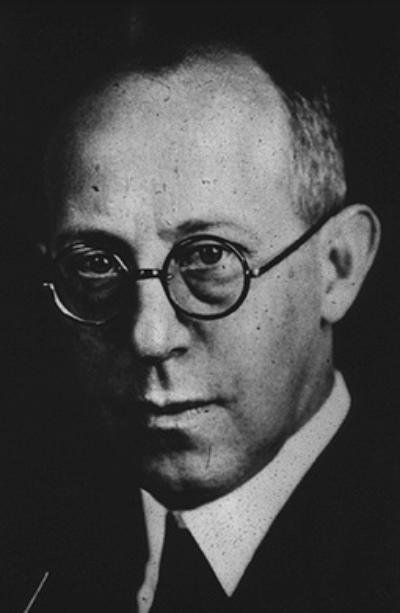

James N. Rosenberg, DORSA's president

James N. Rosenberg, DORSA's president

Much has been written about Trujillo’s motivations for encouraging Jewish immigration to the Dominican Republic. At the time, DORSA leadership and Jewish refugees expressed tremendous gratitude and accepted the help without questioning Trujillo’s motives. In retrospect, it is clear that Trujillo and his regime were not purely altruistic in rescuing Jews fleeing the Holocaust.

Trujillo was a dictator who seized power in a military revolt in 1930. He had no qualms about murdering his political opponents or ordering a massacre of Haitian migrants who crossed the border into the Dominican Republic. Dominican citizens lived in fear of being arrested and executed for any action or statement deemed against the regime.

Trujillo himself was of mixed racial descent, a fact that he had tried to conceal by powdering his face before public appearances. He wanted to “whiten” the Dominican people. This could explain why he opposed Haitian migration, as well as why he supported bringing in European Jews, whom he considered white.

In addition, Trujillo hoped to improve relations with the United States. His humanitarian project did indeed raise the U.S. public opinion on his regime. Trujillo also anticipated U.S. investment in the Dominican economy as a result of the project.

Trujillo also had a personal affinity towards the Jewish people. When his daughter, Flor de Oro, attended school in Paris, she was not accepted by the other students due to her darker skin color. The one girl who befriended Flor was Jewish. Trujillo felt grateful to Flor’s Jewish friend.

The desperate Jewish refugees did not ask any questions. They seized the opportunity offered by Trujillo.

Eleanor Roosevelt, President Rafael Trujillo, and Mrs. Trujillo in Dominican Republic, 1934. National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Eleanor Roosevelt, President Rafael Trujillo, and Mrs. Trujillo in Dominican Republic, 1934. National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On May 10th, 1940, the first group of Jewish refugees from Germany arrived in Sosua. The group consisted of 27 men, 10 women, and a baby smuggled out of Germany in a suitcase, with his mouth taped, because his parents didn’t manage to obtain official paperwork to get him out of Germany.

More immigrants arrived in the following months, totaling 252 by the end of 1940. Understandably, there was a lot of interest in Dominican visas among European Jews, who were desperate to leave Europe. DORSA officials were put into an unenviable position of selecting the most suitable candidates among thousands of applications.

As a philanthropic organization, DORSA was dependent on donations and had limited funds. Its goal was for Sosua to eventually become financially independent and self-supporting. In their eyes, Sosua was only the beginning. If this project succeeded, they could expand to other locations in the Dominican Republic, and perhaps, beyond. In the long run, they would be able to get many more Jews out of Europe.

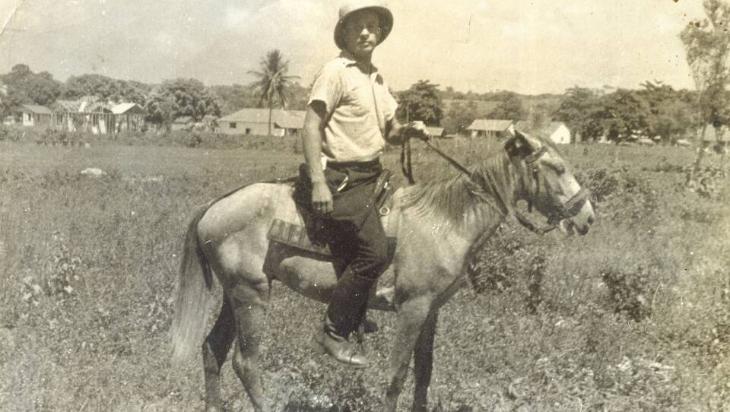

Franz Blumenstein rides a donkey in Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940.

Franz Blumenstein rides a donkey in Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940.

Courtesy, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Therefore, DORSA instructed its representatives to accept for immigration those candidates who had some agricultural experience and a propensity for manual labor. They looked for hard workers who were willing to commit to staying in Sosua long term and to devote themselves to its development and success.

The refugees, on the other hand, had only one goal – survival, for themselves and their families. They were willing to put anything on the application and to sign any paper that would ensure them a Dominican visa. Their responses to the questions indicated what they thought the DORSA representative wanted to hear rather than their own experiences and preferences.

James Rosenberg later wrote that DORSA’s recruiters were “beggars and not choosers.” Only a handful of applicants had actual agricultural experience. Most had no interest in farming and no plans to remain in an agricultural settlement long term.

In addition, DORSA recruiters understood that rejecting an applicant could condemn them to death. So some of the refugees were accepted because DORSA could not abandon them in Europe. And even the promising candidates would only agree to come to the Dominican Republic if they were able to bring their families along. Thus, the majority of the new arrivals in Sosua were not suited for farm work.

The logistics of travel between Europe and the Dominican Republic complicated matters even further. The Jewish refugees traveled by boat to the United States, where they spent up to a week at Ellis Island awaiting the next boat to the Dominican Republic. Therefore, every refugee required a U.S. transit visa in addition to a Dominican visa.

But as the war raged on in Europe, the United States became increasingly concerned about Nazi infiltration. Every foreigner was suspected of spying for the enemy. Even the candidates selected by DORSA had trouble getting U.S. transit visas. Early in 1940, the State Department warned DORSA not to accept refugees from Germany and any Nazi-occupied territory. Later that year, 200 people already accepted by DORSA were rejected by the U.S. State Department and were unable to come to the Dominican Republic.

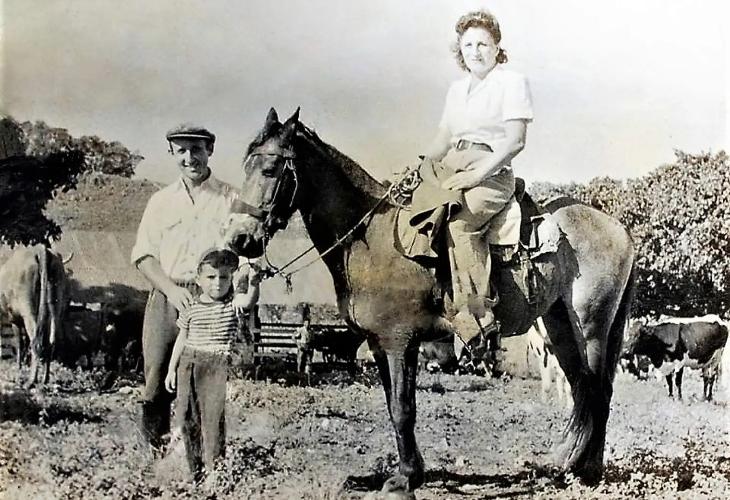

Rene Kirchheimer is pictured as a child with his parents, growing up on the farm in Sosúa in the 1940s.

Rene Kirchheimer is pictured as a child with his parents, growing up on the farm in Sosúa in the 1940s.

An additional factor was the cost of the trip. Due to the war, few ships were traveling between Europe and the United States, and the ticket prices soared. DORSA found itself spending a large portion of its budget on the refugees’ transportation instead of on the development of the settlement.

In October 1941, Germany closed its borders to emigration. Even Jews with means could no longer leave Germany. The first group of immigrants to Sosua was the only one that arrived directly from Germany. The rest came from refugee camps in Switzerland, Italy, and other countries. With no legal permission to remain in those countries, they were living in fear of being deported back to Germany. They saw the Dominican visas as their tickets to freedom, even if they had no intention of staying in the Dominican Republic after the war.

Soon, it became clear to DORSA administrators that it would be impossible to bring anywhere near 100,000 refugees from Europe. Altogether, 5,000 Dominican visas were issued, but only about 750 Jewish refugees made it to the Dominican Republic during the war years. Instead of an agricultural settlement, Sosua was turning into a refugee camp.

(The Dominican visas saved thousands of lives even when their recipients were unable to leave Europe. Jews with foreign visas were not sent to death camps. Based on their own version of diplomacy, the Nazis sent them to work camps, and many of them survived the Holocaust.)

One of the fortunate refugees who made it to Sosua, Horst Wagner, recalls1 that upon arrival, the group encountered “a wonderful view. Before us lay the ocean with a snow white beach. The water was light blue and so clear that one could see to the bottom of the sea. We were thrilled.” Another refugee described Sosua as Paradise.

However, as the reality of life in an unfamiliar tropical climate set in, the settlers found that life in Sosua was less than idyllic. They suffered from unbearable heat and humidity. The air was filled with malaria-carrying mosquitoes. The conditions were primitive, without electricity or running water. The settlers were housed in hastily built barracks, with the intention that they would eventually build their own homes.

Nevertheless, the new arrivals were grateful to be alive and determined to make the best of their new home. They were encouraged by the warm welcome they received from the Dominicans and pleasantly surprised by the absence of any trace of antisemitism. Luis Hess, one of the settlers, later recalled2, “The word Jew was not an insult here. Dominicans treated us as they did any other ethnic group.” Coming from Nazi-ruled Europe, the settlers were truly moved by such acceptance. Another settler, Otto Papernik, wrote about the locals3, “Even if we could not understand a word they were saying, . . . their friendliness and smiles meant a lot to us.”

The transition to agricultural work was difficult for many of the refugees, who had worked as lawyers, engineers, merchants, and clerks and were not accustomed to manual labor. In addition, the settlers discovered through trial and error that most of Sosua was not suitable for agriculture. The soil was sandy and rocky, and some areas were marshlands. Draught was a common occurrence.

Eventually, the settlers turned to raising cattle and using the land for pasture. Dairy farming became the settlement’s main source of income. By mid-1941, a group of enterprising settlers, supported by DORSA’s initial investment, established a dairy cooperative producing high quality milk and butter. Within a few years, the cooperative captured the butter market of the Dominican Republic. Its other products were also distributed throughout the country.

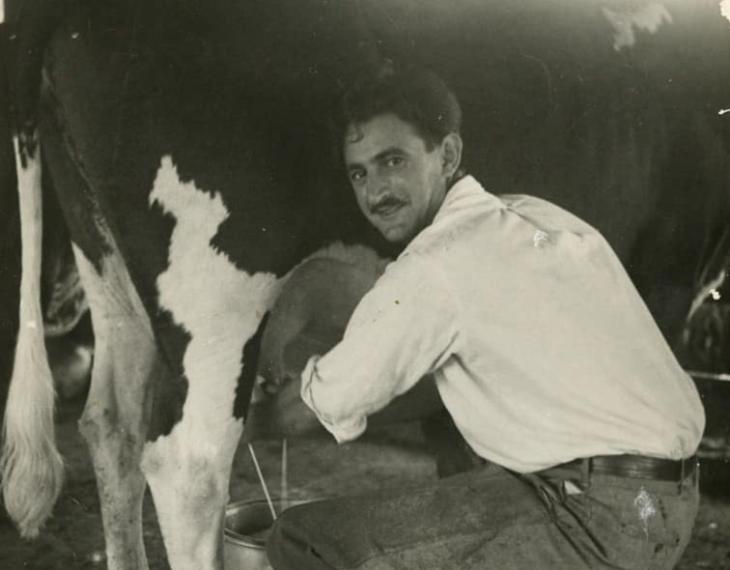

Dezider Scheer milking cow, Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940s. Museum of Jewish Heritage

Dezider Scheer milking cow, Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940s. Museum of Jewish Heritage

Other cooperatives followed, producing meat and sausage. Even the settlers who had given up on farming were finding ways to support themselves. By 1944, Sosua had about 25 shops and small businesses, such as a haberdashery, a seamstress shop, a shoemaker shop, and a plumbing business.

The first years also saw a lot of construction. By the end of 1941, Sosua had 60 houses, in addition to 9 dormitories, a synagogue, a school, a small clinic, and 12 shops and warehouses.

The synagogue in Sosua. Phyrexian, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The synagogue in Sosua. Phyrexian, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Many of the settlers came to Sosua with the intention of eventually bringing over their parents, siblings, and other extended family members.

As the Nazis conquered more and more territory, DORSA was left powerless to fulfill its promises. This caused much conflict between the settlers, who accused DORSA of not doing enough, and the administrators, who accused the settlers of ingratitude for everything DORSA had done for them.

By 1942, both DORSA and the settlers themselves realized that no more Jewish refugees would be able to reach the Dominican Republic until the end of the war. The grand plans for Sosua’s growth and expansion would never be realized.

The effective freezing of the Sosua settlement was demoralizing for everyone involved, including the philanthropists who had invested large sums into the project, expecting it to rescue a significant portion of European Jewry. Instead, this rescue avenue was closed, and European Jewry was in more danger than ever. American philanthropists turned their attention, and their funds, to other rescue efforts. As a result, DORSA found itself struggling financially while the settlement was still nowhere near self-sufficient.

Even the more motivated settlers began to lose faith in the project. The Dominican authorities also grew concerned about what they perceived as a lack of investment on the part of the U.S. In the summer of 1943, the Dominican secretary of interior inspected the settlement and demanded proof that DORSA would continue its investment.

Meanwhile, the settlers had to come to terms with the fact that they were unlikely to ever see their families again. Even the happiest occasions in Sosua were filled with sadness. The first wedding, of Otto and Irene Papernik, was attended by DORSA officials and other settlers, but, Otto recalls4, it was “darkened only by the thoughts that none of our family could be there with us. Especially Irene was very sad, thinking of her little sister, somewhere in a concentration camp and probably alone or not even alive anywhere. I was also very sad.”

Likewise, Passover seder and other Jewish holidays were bittersweet, with the settlers reminiscing about the family they left behind.

Hanukkah celebration in Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940s, Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Hanukkah celebration in Sosúa, Dominican Republic, 1940s, Museum of Jewish Heritage.

For the rest of their lives, the Sosuaners experienced survivor’s guilt. Allen Wells describes his father, one of the settlers, as a flexible person, not discouraged by failure. Wells writes5, “The only failure he would acknowledge was one that tormented him to his grave: his inability to get his family out of Europe. All his pleas to DORSA administrators went for naught, and he never forgave them or himself for not doing enough. Sosúa and Trujillo may have saved his life, but in his mind, there was an unacceptably high price to pay for that privilege.”

Otto Papernik also mentions the heavy guilt. He concludes6, “We tried to forget all the bad things that had happened to… our family and friends, only sadness remained that we were unable to help more, save their lives and get them out, when there was still time. Reluctantly, we survivors had to accept… that we… could not have done more for our loved ones.”

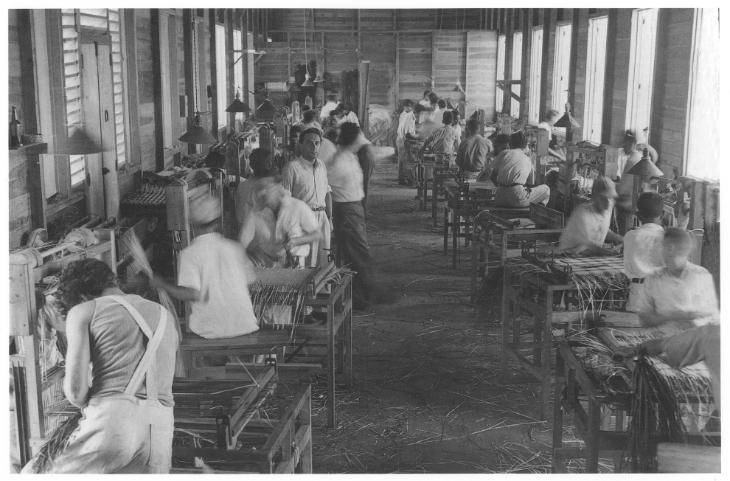

Jewish refugees in Sosúa work in a straw factory making handbags for export to the United States. Unknown author, between 1943 and 1944. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Jewish refugees in Sosúa work in a straw factory making handbags for export to the United States. Unknown author, between 1943 and 1944. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

When the war was finally over in 1945, U.S. President Truman issued a directive on immigration and gave priority to people displaced by the war, especially from Germany7. Since most Sosuaners were German-born, they qualified for immigration. Many Sosuaners jumped at the opportunity to leave the settlement and its farming lifestyle and to emigrate to the United States.

Even those settlers who succeeded in Sosua began to contemplate leaving for America. Otto Papernik had built a successful cabinetmaking shop in Sosua and felt very much at home there. He recalls8, “We, who thought that Sosúa would be our permanent residence, began to worry. We saw our doctors, nurses, barbers, and other professionals leave for the United States and reporting back of a completely different life there. Better sanitary conditions, larger incomes and best of all, regular schools for the children… It was with great sadness when we finally made up our mind to leave Sosúa.” The Paperniks left in 1950.

Single Sosuaners left because they yearned to settle down and begin a family and despaired of meeting their soulmate in Sosua, where single men greatly outnumbered single women.

Schoolchildren sit down for a meal in the Sosúa refugee colony.

Schoolchildren sit down for a meal in the Sosúa refugee colony.

Courtesy, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Married Sosuaners with growing families left because they envisioned a better future for their children. A Sosuaner recalls9, “For a while we lived as in a golden cage. They [DORSA] took care of us… but soon our children grew older… When they reached their teens, we knew it was now or never. We had to leave or face assimilation.”

Within a decade after the war’s end, the majority of those who spent the war years in Sosua left for America.

The DORSA administration felt betrayed by the settlers who chose to leave, despite the huge investment of money and effort into Sosua. They felt that those settlers took advantage of their generosity.

The future of Sosua was now in question. The settlers who stayed expected DORSA to grow and expand the settlement, now that the war was over and migration had become possible. However, Holocaust survivors, especially those interested in farming, chose to go to the newly formed State of Israel rather than the Dominican Republic.

DORSA was in a quandary. Could they approach donors for funds to expand the settlement when funds were desperately needed in Israel? Should they continue investing in what was turning out to be a failed experiment? The matter was heatedly debated in the JDC.

In 1948, Rosenberg resigned from DORSA. In his final report, he wrote10, “[W]e cannot foresee any large scale increase of DORSA work. It may well be therefore we should plan to gradually conclude this effort as one which came into being at a dark hour and which, by acting upon the humanitarianism of President Trujillo, has saved many lives with the continued cooperation of the Dominican authorities.”

The remaining Sosuaners were now on their own. President Trujillo was disappointed that, despite his generous offer of many more visas, the settlement was declining rather than growing. However, Trujillo was not interested in investing Dominican funds into the project.

As many Sosuaners were leaving for America, the last wave of Jewish refugees arrived in Sosua in 1947. They consisted of 90 people who had spent the war years in Shanghai, China. No longer able to remain in China due to its civil war and increasing hostility towards Jews, the refugees were persuaded by JDC representatives to go to the Dominican Republic.

The new arrivals came with their extended families and were warmly welcomed by the veteran Sosuaners. They joined the dairy and meat industry and made a significant contribution. In 1953, a New York Times article reported11 that Sosua was “virtually self-supporting, with assets of about one million [dollars] and no liabilities to speak of.”

Nevertheless, Sosua’s population continued to decline. Some settlers left because they found family members who survived the Holocaust and moved to America. Others yearned for a more urban lifestyle they had enjoyed in Germany and Austria before the war.

The second generation of Sosuaners were even more likely to leave the settlement than their parents. Though they had fond memories of their childhood, many of them left the Dominican Republic to attend university in America and then found employment and settled there.

Today, Sosua is a tourist destination with tourism as its main industry. Out of its approximately 50,000 residents, only several dozen are Jewish.

The Sosua synagogue is still standing. Next to it, the second generation of Jewish Sosuaners built a museum, chronicling the history of the Jewish agricultural settlement. The museum displays DORSA’s archive documents, original farming implements, and many photos and videos of the settlement during the war years and beyond.

Though Sosua’s Jewish settlement did not last, as a second-generation Sosuaner, Joe Benjamin, said12, “Sosúa served its purpose. It saved lives.”

Sosua Jewish Museum. Phyrexian, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Sosua Jewish Museum. Phyrexian, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Sources: