Civil Disobedience: From Midwives in Egypt to Martin Luther King

Civil Disobedience: From Midwives in Egypt to Martin Luther King

4 min read

4 min read

15 min read

7 min read

Long before Martin Luther King Jr., two midwives in Egypt defied an unjust law, launching a tradition of moral courage that still shapes civil disobedience today.

Around the corner from my home in Brookline, Mass., is the William Ingersoll Bowditch House at 9 Toxteth Street. In the 1840s and 1850s, the house was a “station” on the Underground Railroad, part of the elaborate network of secret routes and safe havens that helped 100,000 or more enslaved Black Americans in the United States escape to freedom in the decades before the Civil War.

The Underground Railroad, a great collaborative effort in defense of liberty, was also a massive campaign of civil disobedience at a time when federal law made it a crime to assist freedom seekers fleeing bondage. That means that everyone involved in the Underground Railroad was a lawbreaker — and a moral champion.

I pass that house regularly, and often find myself thinking about the Americans who sheltered refugees there. They knew the law (Bowditch was a lawyer) and understood the penalties they risked by flouting it — prosecution, heavy fines, imprisonment. They did it anyway, because their conscience gave them no choice. The Fugitive Slave Act was lawful, duly enacted by Congress and signed by the president. But it was also profoundly unjust, and the men and women of the Underground Railroad recognized a higher obligation than obedience to such a law.

They were not the first to face that dilemma.

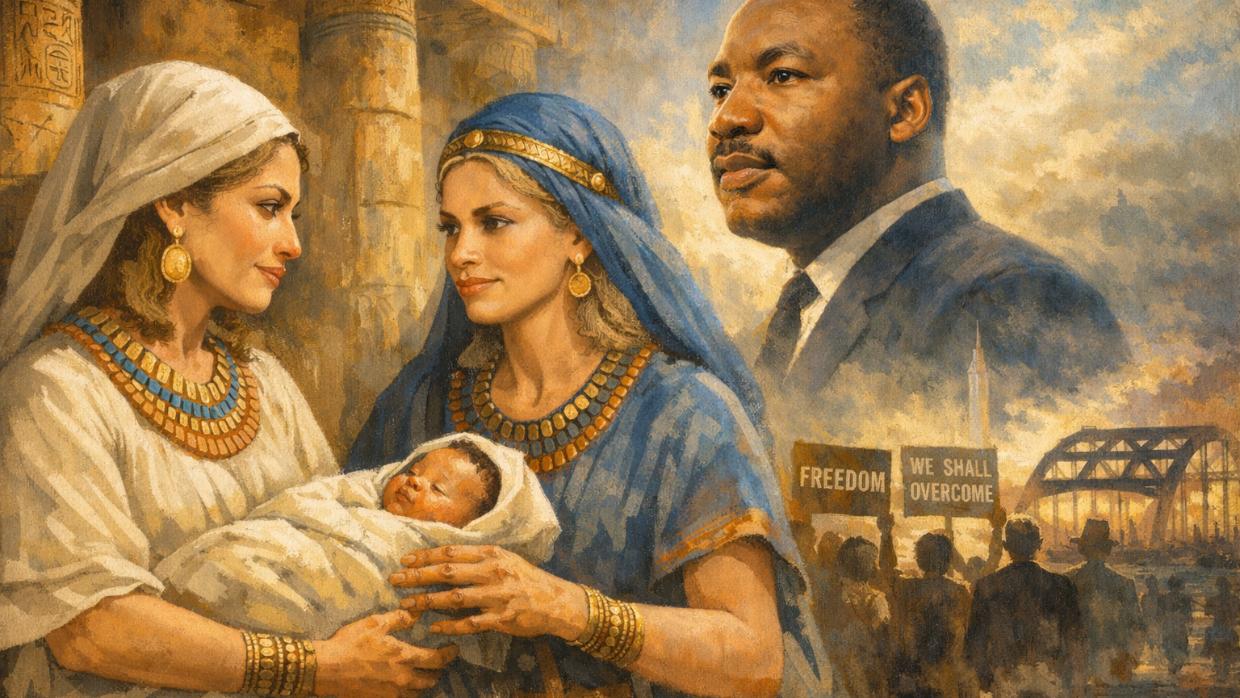

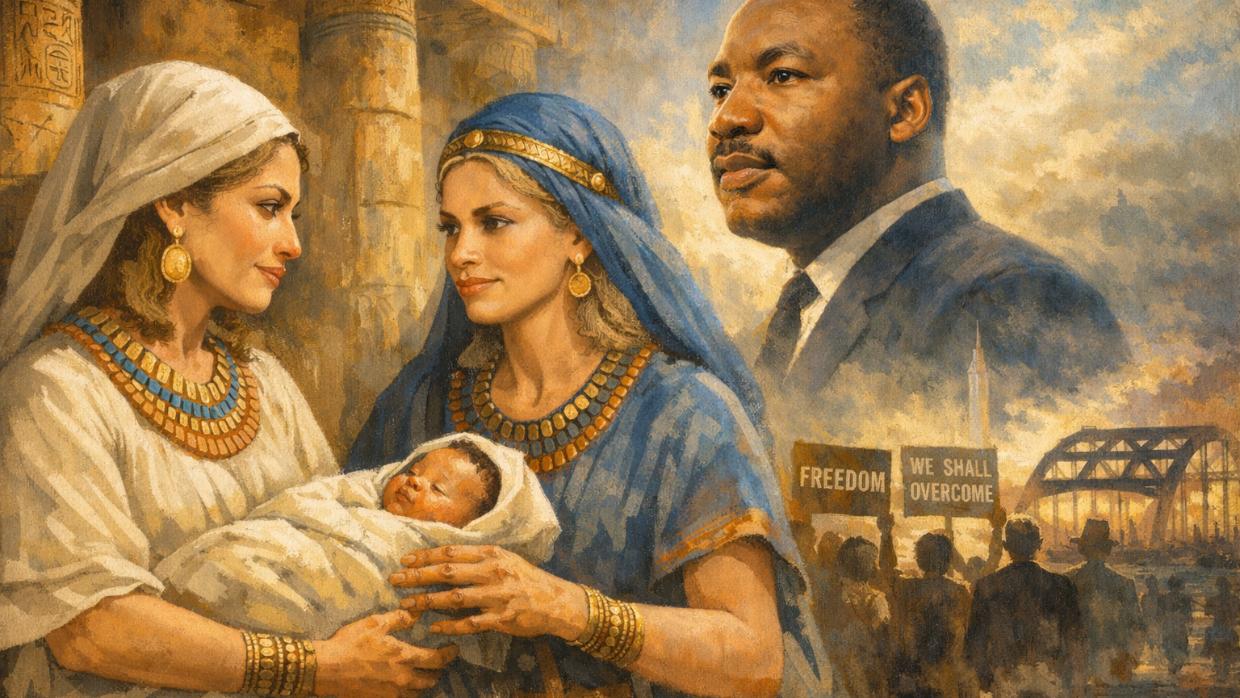

The tradition of righteous lawbreaking reaches back far beyond antebellum America. The earliest recorded acts of civil disobedience were committed by three women, whose stories are told in the opening chapters of the book of Exodus. They came from opposite ends of ancient Egypt’s social ladder. Two were lowly midwives named Shifra and Puah. The third was a princess, the daughter of Ramesses II, the most powerful pharaoh in Egyptian history.

Their tales begin with a genocidal decree. Pharaoh, alarmed by the growing population of his enslaved Hebrews, orders Shifra and Puah to kill every newborn Hebrew boy they deliver. But the women cannot bring themselves to follow such orders. As Exodus 1 relates: “The midwives feared God; they did not do as the king of Egypt commanded them, but they let the boys live.”

When summoned to explain their disobedience, they offer Pharaoh a transparently absurd excuse: Hebrew women give birth so quickly that the babies arrive before the midwives can get there. Their defiance is not merely courageous but bold to the point of mockery.

Shifra and Puah instinctively grasped a principle that would not be codified for many centuries — that some orders are so immoral they must not be obeyed, regardless of who issues them or what punishment disobedience might bring.

This happened in the 13th century BCE, millennia before any theory of civil disobedience existed. The notion of universal human rights was unknown. Yet Shifra and Puah instinctively grasped a principle that would not be codified for many centuries — that some orders are so immoral they must not be obeyed, regardless of who issues them or what punishment disobedience might bring. The text says simply that the women “feared God”— they had a conscience that wouldn’t let them commit murder, even under direct command from the most powerful ruler on earth.

Then, in Exodus 2, comes another act of defiance, equally remarkable.

Pharaoh, thwarted by the midwives, issues a public edict, binding on every Egyptian: All male Hebrew newborns are to be drowned in the Nile. One Hebrew mother hides her infant son as long as she can, then sets him afloat in a basket, hoping desperately that someone might rescue him.

Someone does, and it turns out to be the daughter of Pharaoh himself. She finds the baby, realizes immediately that he’s a Hebrew, and decides to save him anyway. Her handmaids, witnessing this defiance, must surely have warned her of the risk. Yet she stands her ground. Indeed, the princess doesn't simply rescue the child in secret — she adopts him openly and raises him in the royal palace, in direct violation of her father's genocidal decree.

As the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks observed, to get a sense of the magnitude of her act, replace the phrase “Pharaoh's daughter” with “Hitler's daughter” or “Stalin's daughter.” In refusing to assist a homicidal regime into whose highest ranks she was born, she demonstrated that even in the heart of darkness, moral courage is possible.

Pharaoh’s daughter demonstrated that even in the heart of darkness, moral courage is possible.

These women — the midwives and the princess — had nothing in common except their refusal to participate in evil. They acted without the benefit of historical precedent or political theory. But they set the pattern for all those who would choose to fight unjust laws by breaking them and accepting the consequences — people like Rosa Parks, Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi, Oskar Schindler, the Soviet refuseniks, Bowditch and the Underground Railroad abolitionists, and the Dutch couple who helped hide Anne Frank and her family.

Next week, Americans will honor the life and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., whose commitment to civil disobedience in the cause of racial justice made him one of the 20th century’s towering figures. As a Baptist minister, King was of course familiar with the legacy of moral courage that stretches back to Shifra, Puah, and Pharaoh’s daughter. His writings and speeches contain many biblical references, and his philosophy of nonviolent resistance rested on the same foundation as the ancient midwives’: There is a law higher than human law, and decent people must sometimes choose between obedience and justice.

In his renowned “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” written in 1963 while imprisoned for organizing a nonviolent march against segregation, King addressed white clergymen who had criticized him for defying an injunction banning civil rights protests. He drew a crucial distinction between just and unjust orders, arguing that “one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” But unlike those who simply buck authority, King insisted that genuine civil disobedience requires accepting the penalty. “One who breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty,” he wrote. “I submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.”

This was no license for lawlessness or violence. King explicitly rejected both. Those who sat down at lunch counters, who marched in the streets, who refused to move to the back of the bus — they weren’t anarchists or revolutionaries. On the contrary, King argued, they were standing up for America's deepest values, carrying the nation “back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers.”

In truth, they were reaching back even further — back to the midwives of Egypt who stood before the most powerful ruler of their age and said no. Back to the princess who defied her own father's genocidal decree. Back to the first people in recorded history who understood that conscience can demand disobedience, and that such disobedience represents not a rejection of law but its highest expression.

As Americans prepare to honor Martin Luther King Jr.'s legacy, it is worth remembering that his commitment to civil disobedience was neither abstract nor comfortable. It meant jail cells and death threats, beatings and bombs. But King believed, as the Egyptian midwives believed 33 centuries earlier, that some laws must be violated and some orders refused.

The Bowditch House still stands on a quiet residential street, long after the law it defied has been consigned to ignominy. The people who sheltered fugitives there did not know how history would judge them; they only knew what they could not do. That is how moral progress usually begins — not with certainty, but with refusal. That is how it must continue, whenever law demands what conscience forbids.

This op-ed originally appeared in “Arguable,” a weekly newsletter written by Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby.