Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

6 min read

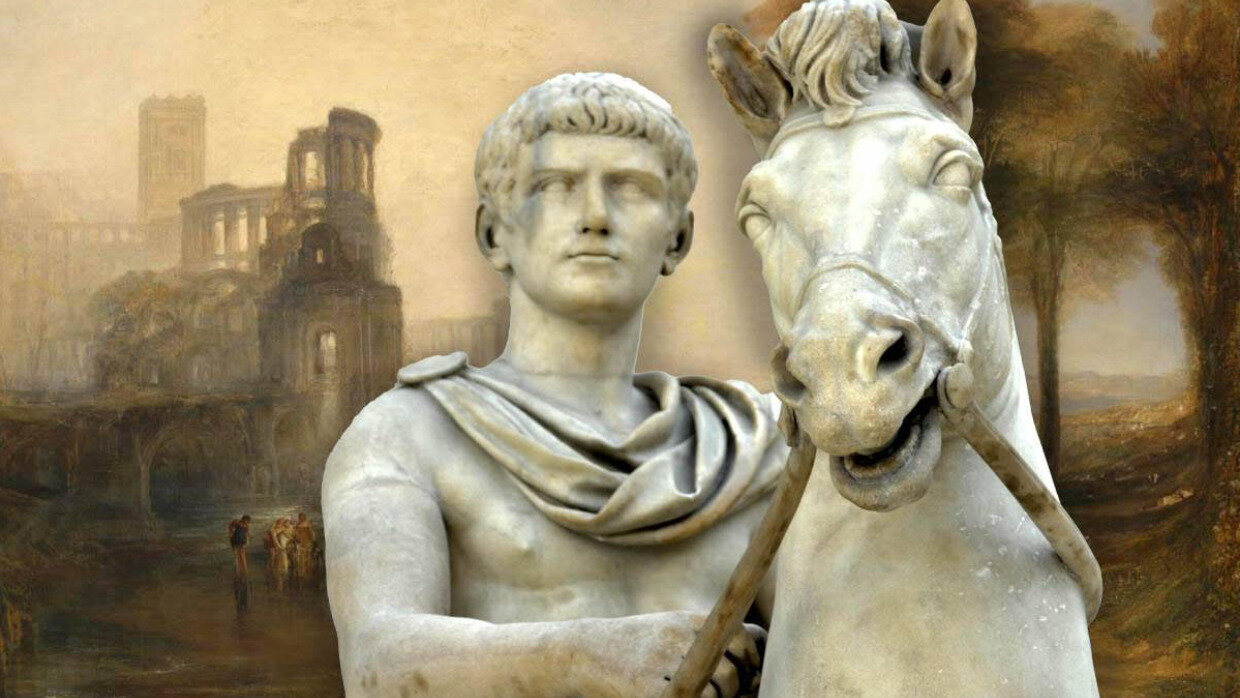

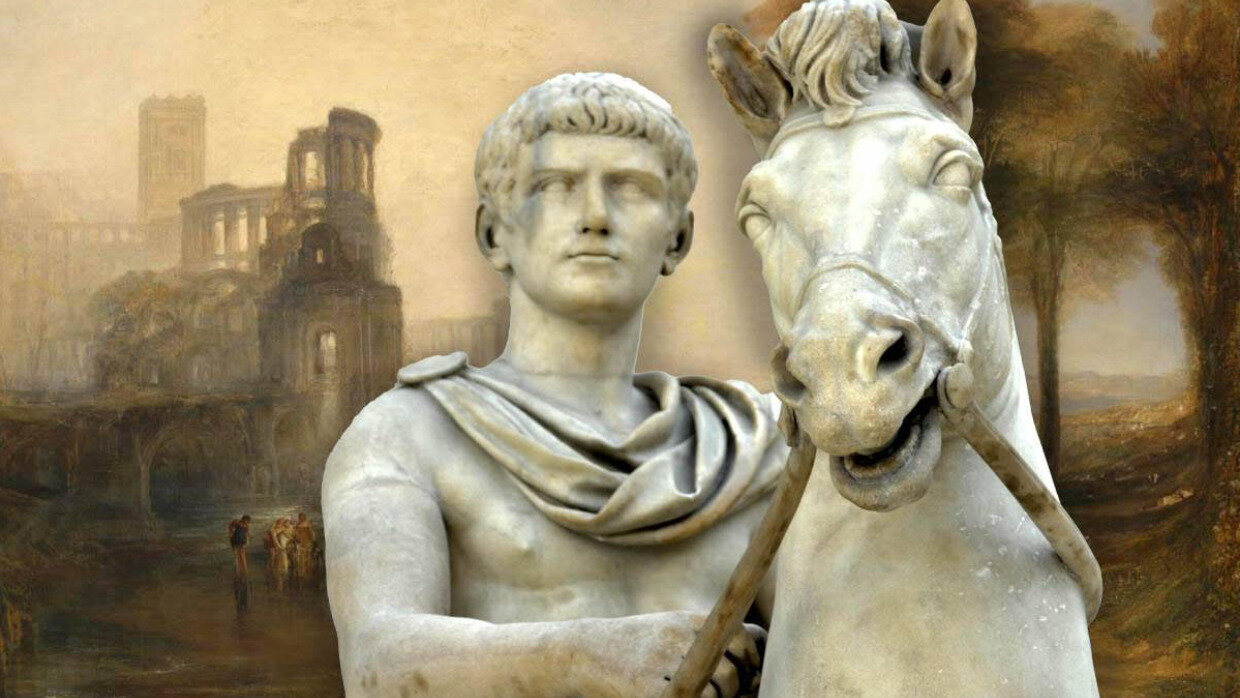

The three strategies Philo used to chip away at Caligula’s irrational antisemitism.

In the year 40 CE, a special delegation from Alexandria’s Jewish community was sent to the Roman emperor, Caligula. Their mission was to dissuade the emperor from his plan to install a statue of himself in the Temple in Jerusalem. Philo, a member of the delegation, recorded their brief but dramatic meeting. It can teach us a great deal about Judaism’s timeless encounter with antisemitism.

Caligula believed that he was a god. When he was informed that the Jewish people were the only nation who refused to acknowledge his divinity, he thought placing his likeness in the Temple would rectify the matter.

Philo realized that to dissuade Caligula, he would have to address his prejudices and offer him a new understanding of Judaism. Reading his account, we can highlight three primary strategies that he used to chip away at the irrationality of antisemitism.

When Philo and the delegation arrived, Caligula showed little interest. Occasionally he paused to interrogate them, but he often ignored or cut off their answers. His goal was to mock them. Like many antisemites throughout history, he highlighted the Jews’ strange customs as an indication that they were hostile to other cultures.

The delegation knew better than to begin a theological discussion with a man who believed himself to be a god. Instead, they chose to emphasize that all cultures have unique customs arising from their traditions, values, or simple preferences.

We can be different without being divided.

“Different nations have different laws,” the delegation explained, noting that the dietary laws of other cultures were often as unusual as their own. While they may appear strange to foreigners, they need not be a reason for ridicule or contempt.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks encapsulates this idea beautifully in his book, The Dignity of Difference:

Most societies at most times have been suspicious of, and aggressive toward, strangers. That is understandable, even natural. Strangers are non-kin. They come from beyond the tribe. They stand outside the network of reciprocity that creates and sustains communities. That is what makes the Mosaic books unusual in the history of moral thought. As the rabbis noted, the Hebrew Bible in one verse commands, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself, but in no fewer than 36 places commands us to ‘love the stranger’… We do not have to share a creed or code to be partners in the covenant of humankind.

Nearly two millennia ago, Philo tried to convince Caligula of this idea. We can be different without being divided.

Caligula further claimed that the Jews must choose between their emperor and their ancestral tradition. If they clung stubbornly to their Judaism, they were traitors. This unwillingness to acknowledge a nuanced middle ground is a recurring antisemitic trope.

Philo was a living refutation of the emperor’s claim. Often considered the first Jewish philosopher, Philo attempted to show the compatibility between the Western philosophical tradition and Judaism’s ancient wisdom. He straddled boundaries – well-educated in secular arts and sciences but equally immersed in Jewish law and thought; a politician working for the public good but also a mystic who longed for solitude. Philo embodied the balance that Caligula claimed was impossible.

“One must pray for the welfare of the government,” teach the Jewish sages. There is no contradiction between being a faithful citizen and a devoted Jew.

Caligula did everything he could to intimidate the delegation and the Jewish people in general. Like countless Jew-hating tyrants, he sought to break their spirit. Before appearing before the emperor, Philo reflected on his likely fate. “And even if we were allowed free access to him,” he wrote, “what else could we expect but an inexorable sentence of death? But be it so; we will perish.”

But if success was unlikely and the threat of death was immanent, why even try? Philo knew that many would look upon his mission as a fool’s errand, and he addressed them with these words:

Men who are truly noble are full of hope, and the [Jewish] laws too implant good hopes in all those who do not study them superficially but with all their hearts. Perhaps these things are meant as a trial of the existing generation to see how they are inclined towards virtue, and whether they have been taught to bear evils with resolute and firm minds, without yielding at the first moment; all human considerations then are discarded, and let them be discarded, but let an imperishable hope and trust in God the Savior remain in our souls, as He has often preserved our nation amid inextricable difficulties and distresses.

Hope was central to Philo’s philosophy of Judaism, and it gave him the courage to defend his fellow Jews, even when everything seemed hopelessly lost. He envisioned a better reality, and he was fortunate enough to witness it. Caligula, seemingly impressed by the delegation’s arguments, concluded that the Jews were not wicked traitors but simply “unfortunate and foolish” for failing to recognize his divinity.

His plans to install the statue never materialized, and he was assassinated by his own guards the following year.

Hope was central to Philo’s philosophy of Judaism, and it gave him the courage to defend his fellow Jews, even when everything seemed hopelessly lost.

In some ways, the antisemitism that Philo encountered seems so different from what we see today. We no longer have emperors who pretend to be gods and command us to worship their statues. But in its fundamental irrationality, there is a common thread between the Jew-hatred of Caligula and the antisemitic rhetoric we are unfortunately hearing today. Historian Paul Johnson perhaps said it best:

If antisemitism is a variety of racism, it is a most peculiar variety, with many unique characteristics. In my view as a historian, it is so peculiar that it deserves to be placed in a quite different category. I would call it an intellectual disease, a disease of the mind, extremely infectious and massively destructive.

Philo sought a way to treat this disease – to reveal its absurdity and replace it with a healthy tolerance and mutual respect. In the case of Caligula, it had an effect. But Philo’s most enduring lesson for us might not be a particular argument or treatment strategy. In the midst of one of Jewish history’s darkest moments, when so much was at stake and so little could be done, Philo modeled a Judaism that was unyieldingly full of hope, for his time and for ours.