An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

19 min read

A history of Jews in the holy land, from Roman times through the Mamluk period.

There is a common misconception that Jews living in the Land of Israel is a recent phenomenon. Some go so far as to accuse Jews of “settler colonialism,” attempting to replace the indigenous inhabitants of the Land of Israel. In fact, Jews have been the indigenous inhabitants of the Land of Israel for thousands of years. Even after Rome took control of the Land of Israel in 61 BCE and destroyed the Second Temple in 70 CE, large Jewish communities remained in the Land of Israel.

In the ensuing 2,000 years, these communities experienced wars, persecution, poverty, and sometimes even destruction, but Jews have been returning and rebuilding them greater than ever before. While many Jews were forced to leave the Land of Israel, they yearned to return, and some of them or their descendants eventually did.

Since the Romans, the Land of Israel was ruled and fought over by the Byzantines, the Muslims, the Crusaders, the Mamluks, the Ottoman Empire, and the British. During all those time periods, Jews came and settled in the Land of Israel, strengthening the existing communities and establishing new ones. Here are some of their stories.

Synagogue floor, Beit Shean, 5th-7th century CE. Source: Israel Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Synagogue floor, Beit Shean, 5th-7th century CE. Source: Israel Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the beginning of the Byzantine rule, after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 4th century CE, Jewish population in the Land of Israel was quite large. In fact, Rabbi Yochanan in the Jerusalem Talmud 1 states that most of the land was under Jewish ownership. Rabbi Elazar disagrees, but the fact that this is discussed shows that a large percentage of land was owned by Jews.

Until some time after Byzantine Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in 312 CE, Jews constituted the majority of the population in the Land of Israel 2.

As the Byzantine Empire became more Christian, its rulers expanded much effort to build churches and monasteries in the Land of Israel, and more and more of its citizens began moving there. With the Byzantine Empire’s official acceptance of Christianity as a state religion towards the end of the 4th century came a wave of persecutions aimed at converting the Jews or forcing them to leave. Many Jews moved elsewhere and the population became predominantly Christian.

However, a sizeable number of Jews remained, concentrated mostly in the north. They maintained community infrastructure, such as educational institutions and rabbinical courts.

Even during this difficult time, there were Jews who moved to the Land of Israel. Among them was Mar Zutra from Mechuza in Persia, a scion of the Davidic dynasty 3. Mar Zutra’s story begins with a tragedy. He was named after his father, the Exilarch, who was charged with rebellion and executed by the Persian Empire. Mar Zutra is said to have been born on the day of his father’s execution.

There is a disagreement among historians about whether Mar Zutra escaped to the Land of Israel as a child or moved there as an adult, after having served as an exilarch in Persia for decades. What’s clear is that he settled in Tiberias, where he was given the title of Reish Pirka – Head of Sermons – and appointed the head of the Rabbinical court. Among his achievements is spreading the study of the Babylonian Talmud outside of Babylonia.

Rabbi Chaim Dov Rabinowitz writes 4,

Mar Zutra’s arrival in the Land of Israel came at an opportune time for the Jewish community of the land. His influence filled an urgent need for leadership which, following the crushing disappointments it had suffered over the past centuries, the weary Jewish community in the land had great need of.

Mar Zutra strengthened the Jewish community in the Land of Israel and contributed to its growth. After his death, his children took over the mantle of leadership for several generations 5.

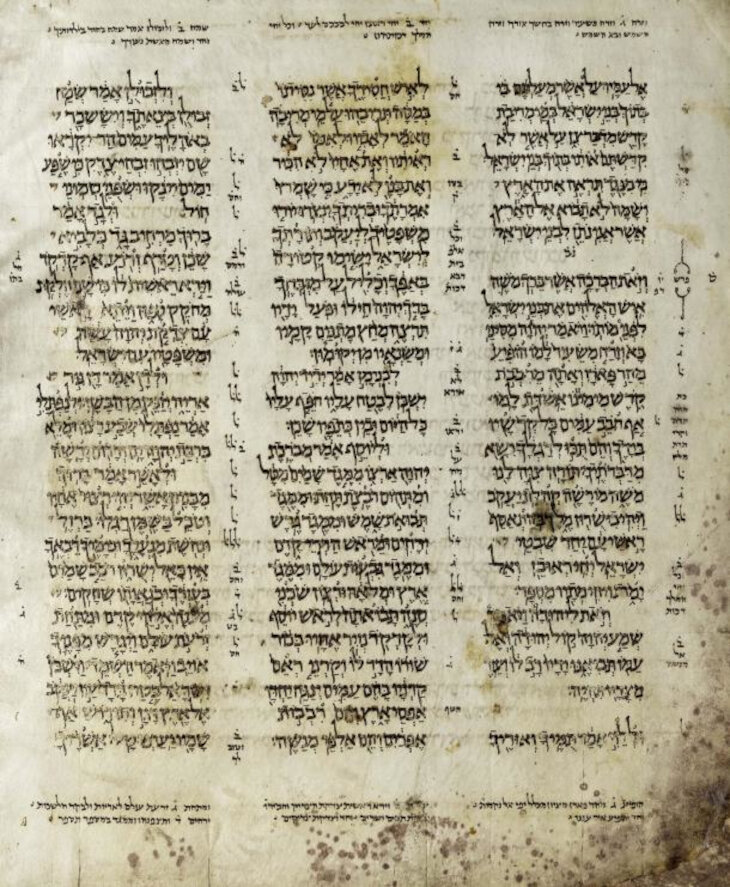

A section of the Aleppo Codex, the earliest known full text of the Torah, written in 10th century Tiberias. Source: Yad Ben Zvi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A section of the Aleppo Codex, the earliest known full text of the Torah, written in 10th century Tiberias. Source: Yad Ben Zvi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When Caliph Omar conquered the Land of Israel in 627 CE, he improved the conditions of the Jews living there and even permitted seventy Jewish families to settle in Jerusalem, for the first time in 500 years.

Over the years, the population of the Land of Israel became predominantly Muslim. While the Muslims treated Jews as inferiors, they did not object to Jewish presence in the land. As the region gained political and economical stability, the Jewish communities began to rebuild and grow.

During this time, another prominent scholar moved to the Land of Israel. His name was Rav Acha, also known as Achai Gaon, and he had been teaching in the famous Talmudic academy in the city of Pumbedisa in Babylonia. When the head of the academy passed away, Rav Acha was the most qualified to take his place. However, the Exilarch of the time, for reasons not preserved by history, appointed Rav Acha’s student instead 6.

Perhaps looking to contribute to the Jewish community in a more significant way, Rav Acha moved to the Land of Israel and brought along many of his students 7. There, he received the title of Reish Pirka that had until then been reserved for the descendants of Mar Zutra.

Meir Holder quotes Rabbi Yaakov Emden, a leading 18th century German rabbi and Talmudist 8:

R’ Achai strengthened tenfold the fortress that Mar Zutra had commenced to build for the Babylonian Talmud in Eretz Yisrael [Land of Israel], and it was from there that the Talmud spread to all the nearby countries of the West.

In the Land of Israel, Rav Acha authored Sheiltos D’Rav Achai Gaon, the first rabbinical text written after the completion of the Talmud. Addressed to the layman and arranged around the weekly Torah portion, its aim was to encourage Torah study among the Jewish population.

Tombstone of the Ramban and the Tosafists in Haifa. Source: שמזן, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tombstone of the Ramban and the Tosafists in Haifa. Source: שמזן, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Under the pretense of conquering the Holy Land from the Muslims, the Christian crusaders sowed death and devastation wherever they went. In the Land of Israel, they slaughtered both Jews and Muslims mercilessly, destroying whole communities. In Jerusalem, during the First Crusade in 1099 CE the crusaders burned all the Jewish residents alive inside the main synagogue 9.

And yet, even those dark days saw some rays of light. Rabbi Rabinowitz explains 10:

The Jews of Israel were for the most part concentrated in the Galilee… [When they heard about the Crusaders’ advance,] many of the Jewish inhabitants of Jerusalem fled the city and found refuge there too. This region of dense Jewish settlement was left unharmed. There is evidence of the fact that a certain number of European Jews made use of the passage opened up for them to the Land of Israel by the Crusaders, made aliyah 11, and settled in the land.

Even though some Jewish communities in the Land of Israel were wiped out, other towns and villages absorbed the refugees, and their communities grew. In addition, Jews from Europe began arriving in the Land of Israel, strengthening the local communities both physically and spiritually.

A 16th century chronicle states 12:

In the year 4971 (= 1211 C.E.), G-d inspired the Rabbis of France and England to go to Jerusalem. They numbered more than three hundred and were accorded great honor by the king. They built for themselves synagogues and houses of study. Our teacher the great kohen R. Jonathan ha-Kohen went there as well. A miracle occurred. They prayed for rain and were answered, and the name of Heaven was sanctified because of them.

While the number 300 is difficult to verify, there is evidence of several famous rabbis from Europe traveling to and settling in Acre and Jerusalem over the years 1210-1212. Among them are Rabbi Joseph of Clisson, his brother Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Samson of Sens, Rabbi Baruch ben Isaac of Worms, and Rabbi Samson of Coucy. 13 It seems that the rabbis did not travel all together, nor did they settle in the same location.

Rabbi Rabinowitz writes 14,

This wave of aliyah was no doubt organized from the beginning and had definite goals, except that we have no record of their details. The splitting up of the group between those who settled in Acco [Acre] and in Jerusalem indicates a plan by which those sages who planned to dwell in Jerusalem, the country’s center, would retain a sea outlet in Acco. Through it, they would be able to maintain contact with the Jewish centers of Europe.

In an ironic twist of history, it was precisely the Crusades that enabled the establishment of a new yeshiva in the coastal city of Acre and the development of Acre’s Jewish community.

The story began in 1240, when Rabbi Yechiel of Paris, the head of the Paris yeshiva, was forced to participate in a Christian-Jewish disputation at the court of King Louis IX. Even though Rabbi Yechiel and his colleagues valiantly defended the Talmud, the king ordered all copies of the Talmud in France confiscated and burned in Paris in 1242.

Following this tragic incident, Rabbi Yechiel decided to leave France. Meanwhile, King Louis IX headed on another Crusade. Rabbi Berel Wein writes 15:

Accompanying the French knights on their journey to the Holy Land were three hundred Jewish scholars, disciples of Rabbi Yechiel of Paris and other great Tosafists 16, who thereupon established a strong Jewish community and yeshivah [Talmudic academy] in Acre under the toleration and protection of the Crusaders!

As above, the exact number of Jews that made their way to the Land of Israel together with the Crusaders is difficult to verify. However, it is known that Rabbi Yechiel reestablished his Talmudic academy in Acre, calling it Midrash HaGadol d'Paris (the Great Academy of Paris).

Professor Sylvia Schein writes 17,

By the 1250’s, Acre, … the city in which the largest Jewish community in Palestine was located, became one of the most important centers of Jewish studies in the Middle East. This was a result of the migrations of the Tosafists. The ordinances (taqqanot) of this city’s rabbinical court were often accepted by all the communities of the Kingdom as well as of those of Egypt and Syria. According to a responsum of R. Solomon Adret (Rashba) of 1280: “It is a custom among the sages of the Holy Land and of Babylon, that if a question should be asked, nobody answers but says, ‘Let us be guided by the sages of Acre.’”

Even during the difficult era of the Crusades, the Jewish community in Acre not only grew but also was able to maintain the leading Talmudic academy of the time.

Another notable personality that came to the Land of Israel in the 13th century was Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, the Nachmanides, also known as the Ramban. His story, just as Rabbi Yechiel’s, also began with a Christian-Jewish disputation, which took place in Barcelona in 1263, in the presence of King James I of Aragon. At the request of the bishop of Gerona, the Ramban had recorded the proceedings of the disputation in a book.

Just as in Paris, the outcome of the disputation was predetermined. While the king appreciated the Ramban’s arguments and even rewarded him with 300 solidi, the local clergy was furious.

Historian Yitzhak Baer writes 18,

In a letter to James I… [Pope] Clement IV demanded the punishment of the man who had “composed a tract full of falsehood concerning his disputation… in the presence of the king, and even circulated copies of the book in order to disseminate his erring faith.” R. Moses ben Nahman departed for Palestine shortly thereafter, arriving in Jerusalem on the 9th of Elul 5027 (1267), and, while this pilgrimage was the realization of the lifelong aspiration of this sage and mystic, one cannot escape the conclusion that his old enemies, the Dominicans, had made life unbearable for him in Catalonia.

The Jerusalem that the Ramban encountered on his arrival was a sorry sight, devastated by centuries of battles and conquests. In a letter to his son 19, the Ramban wrote that most of its 2,000 residents were Muslim, with about 300 Christians and almost no Jews. He writes, “There are only two brothers, dyers by trade, who buy their dyes from the ruling power. It is in their house that the Minyan [traditional quorum of ten men] gathers for the prayers on the Sabbath.” The rest of the minyan would come from the outlying areas.

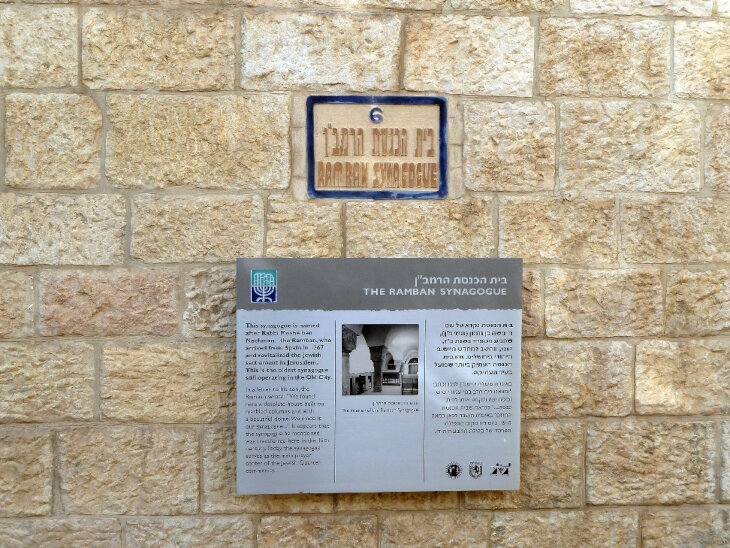

The Ramban was determined to establish a proper synagogue in Jerusalem. He found an abandoned, ownerless building “with marble columns and a beautiful cupola 20.” In the new location, the minyan grew, and so did the Jewish community of Jerusalem.

Eventually, the Ramban synagogue, as it became known, moved to a different building, located in what today is the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. The building was destroyed in 1948 and rebuilt after 1967. Still called the Ramban synagogue, it is in active use today.

The inscription and sign on today's Ramban Synagogue in Jerusalem. Source: Utilisateur:Djampa - User:Djampa, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The inscription and sign on today's Ramban Synagogue in Jerusalem. Source: Utilisateur:Djampa - User:Djampa, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the second half of the 13th century, the Mamluk Sultanate began its invasion and eventual conquest of the Land of Israel. The Mamluks put an end to crusades. They destroyed all the port cities on the Mediterranean in order to prevent any more crusaders from coming in. The formerly thriving Jewish community of Acre was destroyed. There is very little information on what happened to survivors, if there were any.

Professor Michael Ehrlich 21 suggests that the Jewish refugees and survivors from the coastal cities relocated to Safed and Jerusalem. Both communities grew significantly under the Mamluks.

In 1488, Jerusalem’s Jewish community was further strengthened with the arrival of Rabbi Ovadiah from Bartenura. In a letter addressed to his father 22, he shares his first impressions of the city:

Most of Jerusalem is in ruins, and it goes without saying that there is no wall about it. According to what I was told, a total of four thousand families live in Jerusalem. But of these, only seventy are Jewish, the poorest of the poor, who earn no money. Almost everyone lacks basic food items. If someone has enough food for the year, he is considered wealthy. There are many old and lonely widows, Ashkenazi, Sephardi and from other lands, “seven women to a man.”

The Muslims do not oppress the Jews at all here. Wherever I travelled, through the length and breadth of the land, no one said a word to me. The Muslims are very kind to foreigners, and, in particular, to someone who does not speak the language. Even when they see many Jews gathered together, they are not hostile.

Immediately after his arrival, Rabbi Ovadiah threw himself into helping the community, from burying the dead to attempting to restore justice. But his main goal was teaching Torah. In 1489, he writes to his brother 23:

I am happy with my work here in Jerusalem, and no one bothers me. We gather in the morning and evening to learn Halachah [Jewish law]. Two Sephardi students learn with me regularly, and now two Ashkenazi rabbis have joined us.

Both his scholarship and his dedication to community causes did not go unrecognized, and Rabbi Ovadiah soon became the undisputed leader of the Jerusalem Jewish community. In 1492, Rabbi Ovadiah fulfilled his dream of opening a Talmudic academy in Jerusalem. It drew many students, a large percentage of them recent exiles from Spain.

A student who traveled from Venice to join the academy describes what he found on his arrival 24:

Rabbi Ovadiah is very great, with a good deal of influence. No one dares raise a finger against him. Jews stream to him from the ends of the earth and obey his every word. When he makes a decree it is enforced as far away as Egypt and Babylon. Even the Muslims honor and fear him.

…

When I first came to Jerusalem, I had a great deal of trouble finding a house to live in, because many people had come here, and it was quite crowded. I rented a room for a month until I could find a permanent place.

…

There are about two hundred Jewish families in Jerusalem. They are very careful not to commit any transgressions, and they are punctilious about doing mitzvos [Torah commandments]. Evening, morning and noon, they gather together, the well-off and the poor, to pray with a great deal of feeling. There are two G-d-fearing cantors who pray carefully and slowly. Twice a day, the entire community gathers to hear words of Torah in the beis midrash [study hall] delivered by an eighty-year-old man, a wise and intelligent rabbi named Zechariah of Spain.

The exact year of Rabbi Ovadiah’s passing is a subject of dispute, but over the course of his leadership, the Jewish community of Jerusalem grew both physically and spiritually. Their living conditions improved, and their scholarship flourished. The academy continued to operate long after Rabbi Ovadiah’s death.

Grave of Rabbi Ovadiah from Bartenura in Jerusalem. Source: מאת מיכאל יעקובסון, ייחוס

Grave of Rabbi Ovadiah from Bartenura in Jerusalem. Source: מאת מיכאל יעקובסון, ייחוס

In 1492, Jews were expelled from Spain. As a consequence of this unfortunate event, many of the exiled Jews made their way to the Land of Israel. Rabbi Berel Wein quotes Don Yitzchak Abarbanel 25:

In the year (5)252 (1492) the Lord aroused the rulers of Spain to expel from their land close to three hundred thousand Jews, and the Jews left the West, and turned toward the Land of Israel. Not only the Jews, but even the anusim (conversos) who left the fold of Torah, continually travel there. In this fashion do they all gather in the Holy Land.

Rabbi Wein explains 26:

Even though the bulk of Sephardic refugees from Spain settled in Italy, Greece, Turkey and Holland, a small but important segment of Sephardic Jewry arrived in the Land of Israel in the sixteenth century. Actually, a constant trickle of Sephardic Jews had been reaching the Holy Land since 1391, and after 1492, organized Sephardic immigration began to increase.

Many of these Sephardic newcomers settled in Safed. Rabbi Wein writes 27, “By 1505, the Sephardim were the majority of that community and were its leaders.”

Rabbi Rabinowitz writes about Safed:

The region surrounding the city is blessed with a soil and climate which allows for the development of olive groves, herds of sheep, beehives for honey, and a perfume industry. Within a short time the able Spanish Jews turned Safed into a major commercial center. They brought much merchandise to the city from Turkey and other lands, and developed local production too. Most Spanish Jews succeeded in taking their money and belongings out of Spain, and many invested their wealth and energy in Safed.

Unlike other lands where Spanish exiles reestablished themselves after their expulsion, a spiritual center of outstanding importance was quickly founded in Safed. A Hebrew printing house was also set up there, which allowed the speedy dissemination of Torah works throughout the world.

Both the Jerusalem and the Safed Jewish communities experienced growth and development in the Mamluk period, but even more opportunities were afforded the Jews there after the Ottoman conquest.

Part 2 of this series will discuss Jewish life in the Land of Israel from the Ottoman conquest through the 18th century.

The interior of the Abuhav synagogue in Safed, built by new arrivals from Spain shortly after the expulsion. Source: Roylindman at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The interior of the Abuhav synagogue in Safed, built by new arrivals from Spain shortly after the expulsion. Source: Roylindman at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

I'm always interested in how people depict history. I have a tendency to point out the hard truths that everyone hates addressing but needs to be heard. This article alluded to but didn't say it straight out. Earlier in this history, while muslims politically tolerated the presence of Jews in their countries, this does not mean the muslim community as a whole didn't hate us and want to exterminate us. And this all changed when we Jews would have land of our own that we govern, and not under the oppressive thumb of muslims. Now muslims as a whole politically will not tolerate us simply because we have a land of our own, and are focused on exterminating us along with any country that supports us. When I was in Mosul, muslims frequently attacked the Jewish Quarter to kill Jews.

Very interesting. For those who don't know when the Muslim rule and the Crusades began, it would have been good to have included those dates.

Lovely! Very informative.