An Open Letter to University Presidents

An Open Letter to University Presidents

8 min read

Lillian Wald revolutionized the medical field and was a fierce advocate for women’s rights, women’s suffrage, equal rights for Black Americans.

Public health nursing benefits millions of people around the world today, allowing patients to be seen in their own homes instead of in hospitals or doctors’ offices. The term was coined by Lillian D. Wald, a little-remembered Jewish nurse, who devoted her life to making the world a much better place.

When Lillian was born in 1867, her family enjoyed a comfortable life in Cincinnati. Her father Max’s and her mother Minnie’s families had recently moved from Europe to the United States; Lillian was the third of their four children. She later remembered herself as a “spoiled” child, indulged by her doting grandparents.

The Wald family soon moved to Rochester, New York, where they were active in the Jewish community. Lillian attended a prestigious boarding school which taught students in both French and English, and was a brilliant student. She applied to Vassar College at the age of 16 but was turned down because she was so young. Little did she realize, Lillian was about to have an experience that would alter the course of her life forever.

Lillian was present when her sister Julia had a baby, and Lillian decided that nursing was her life’s calling. She attended nursing school at New York Hospital’s Training School, then embarked on another degree at the Women’s Medical College in New York. While she studied, Lillian worked at an orphanage and helped teach a class about health for immigrants on New York’s Lower East Side.

The contrast with her own family life couldn’t have been more extreme. Years later, on a visit to Rochester, Lillian noted: “In coming back to Rochester, I inevitably compare the physical advantages of the children who are brought to manhood and womanhood in this environment with those of the children (in the poor precincts of New York City) with whom my lot in life has been cast these many years.” Viewing the extreme poverty of the largely Jewish Lower East Side in the 1880s, Lillian knew she had to make a difference, creating major new public health resources to help her fellow Jews.

Immigrants - many of them Jewish - poured into New York’s Lower East Side in the second half of the 1800s. By the year 1900, the Lower East Side was the most crowded neighborhood in the world, with over 700 residents per acre. Many immigrants toiled in poorly ventilated, unsafe sweatshops; others worked round the clock sewing piecework in overcrowded tenement apartments. Disease and malnutrition were rampant.

Social reformer Jacob Riis described the conditions in a tenement occupied by Jewish families: “I have found in three rooms father, mother, twelve children, and six boarders. They sleep on the half-made clothing for beds. I found that several people slept in a subcellar four feet by six, on a pile of clothing that was being made.”

For Lillian Wald, a turning point came one day when she visited a young woman in a tenement building. She later described the experience as “a baptism of fire.” She wrote, “Deserted were the laboratory and academic work of college. I never returned to them…I rejoiced that I had a training in the care of the sick that in itself would give me an organic relationship to the neighborhood in which this awakening had come.” (Quoted in The House on Henry Street by Lillian D. Ward. H. Holt, New York: 1915).

Seeing the family’s ragged condition and ill health, Lillian decided that providing a new model of health care to these impoverished immigrants must be her life’s work. She dropped out of medical school. At the time, idealistic young women were establishing “College Settlement Houses” in many American cities, where educated women could provide education and social care for the poor. Lillian moved into a College Settlement House in New York’s Lower East Side where she found a community of like-minded, visionary women, and a forum in which she could work to help others.

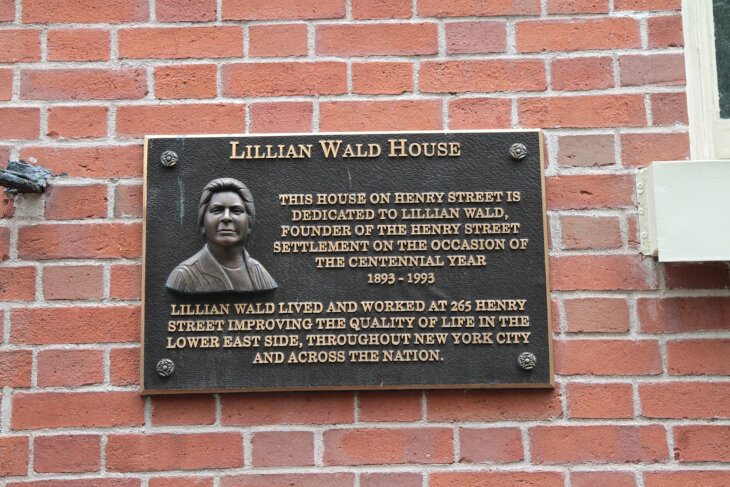

In her Settlement House - known as the Henry Street Settlement, which still exists today, serving residents of the Lower East Side, Lillian developed a new philosophy of nursing. As the University of Pennsylvania’s Nursing School describes, “Wald’s practice among the sick poor quickly convinced her that their diseases most often resulted from causes beyond an individual’s control…By looking at nursing practice from the patient’s point of view, encouraging personal and public responsibility, and providing a unifying structure for the delivery of comprehensive, equally available health care, Wald conceptualized a new paradigm for nursing.”

Hester Street Fair, 1898

Hester Street Fair, 1898

In order to ensure her patients were healthy, Lillian realized she needed to help them in all sorts of ways, from advocating for better pay and infrastructure, to educating people about public health, in addition to providing traditional nursing care. She also treated poor patients as equals, listening to their concerns, and encouraged other nurses to do the same. In the Victorian age, this attitude of investing the poor with dignity was revolutionary.

Lillian later described the genesis of her idea in her memoirs: “We planned to create a service on terms most considerate on the dignity and independence of the patients. We felt that the nursing of the sick in their homes should be undertaken seriously and adequately…that the nurse should be as ready to respond to calls from the people themselves as to calls from physicians….” (Quoted in The House on Henry Street by Lillian D. Ward. H. Holt, New York: 1915).

In 1885, Lillian, along with her good friend Mary Brewster, who was also a nurse, set to work. They hired six other nurses, as well as social activists, including lawyers and union organizers. They converted the backyard of the Henry Street house into a playground, the largest in the entire Lower East Side. Lillian and her colleagues also organized a full roster of social events. Neighborhood immigrants could sign up for vocational classes in the house, go on Henry Street Settlement picnics and other outings, visit the countryside, and experience the wider world of New York City and beyond.

Ever the social pioneer, Lillian hired a Black nurse for the first time in 1906, at a time when it was exceedingly rare for organizations to employ both Black and white employees. She went on to hire several other Black nurses, and lent the Henry Street Settlement to the pioneering civil rights organization the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) for meetings.

Lillian Wald with Jane Addams in Washington, D.C., 1916; Library of Congress Photo Collection

Lillian Wald with Jane Addams in Washington, D.C., 1916; Library of Congress Photo Collection

Over time, Lillian opened nine other locations of the Henry Street Settlement. By the time she retired in 1933, the organization she led employed 265 nurses who cared for 100,000 patients.

Public health nurses began to have a real effect. Patients paid what they could; Lillian’s Henry Street Settlement House relied on charity to keep running. Lillian began lecturing students in Columbia University’s Teachers College, and helped set up Columbia University’s Department of Nursing and Health in 1910. Lillian advocated for an independent organization to set nursing standards in the United States, and served as the first president of the resulting National Organization of Public Health Nurses (NOPHN).

Lillian never stopped working to make the world a better place. She helped found the United States Children’s Bureau, National Child Labor Committee, and National Women’s Trade Union League. In 1918, she led the Red Cross’s efforts to eradicate the Spanish Flu pandemic. Throughout her life, Lillian advocated for women’s rights, women’s suffrage, equal rights for Black Americans and others, and work safety standards. She helped create the concept of special education classes in New York City public schools, and helped invent the institution of school nurses. In 1922, The New York Times named Lillian one of the 12 greatest living American women.

Henry Street Settlement

Henry Street Settlement

When she died in 1940, she had a Jewish funeral, then a massive public memorial service in Carnegie Hall. Over 2,000 people attended her memorial service, including the Mayor of New York City and the Governor of New York State.

In her memoirs, The House on Henry Street (1915), Lillian looked back on her work and noted that: “Never in all the years have we on Henry Street doubted the validity of our belief in the essential dignity of man and the obligations of each generation to do better for the oncoming generation.” Indefatigable even in the face of apathy and setbacks, Lillian never lost her burning belief that she could help make the world a kinder, fairer place.

Impressive Jewish female role model and heroe!

Great article about a great woman. However, Woodrow Wilson did not attend her 1940 funeral. He passed away in 1924.