Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

5 min read

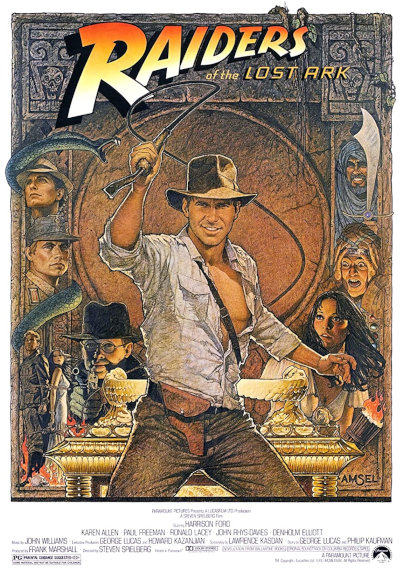

The Ark of the Covenant isn’t the only Jewish reference in “Raiders of the Lost Ark”.

When “Raiders of the Lost Ark” hit theaters in 1981, the world got its first taste of dashing hero Indiana Jones. But for Jewish audiences, the film meant something more. The lost ark of the title is the Ark of the Covenant, which features heavily in Jewish history, from its first appearance in the book of Exodus until its disappearance just before the Babylonian conquest.

The Jewishness of Indiana Jones doesn’t end with the ark. Let’s peel away the layers and see what we can find:

Dr. Belloq wearing the priestly garments

Dr. Belloq wearing the priestly garments

In the film’s climax, the villain, Dr. Belloq (played by Paul Freeman), wears an unusual outfit in preparation for the ritual opening of the ark. The outfit is a rough approximation of the vestments of the High Priest, the Kohen Gadol, which are described in detail in the Torah. He even wears an ephod, the breastplate with 12 precious stones that the High Priest used to wear. The costume was designed by Deborah Landes, who is Jewish, too.

When Belloq opens the ark, he recites something that’s meant to sound like Hebrew. It's actually a few Aramaic words from a prayer that is recited all over the world when the synagogue ark is opened.

For this moment, the screenplay (by MOT screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan) instructs, “He utters a short phrase in Hebrew,” without specifying what that short phrase should be. It’s likely that Kasdan didn’t know enough Hebrew to suggest one.

Of course, Steven Spielberg, who not only directed “Raiders,” but was heavily involved in shaping the story, is also Jewish. Like many American Jews, Spielberg had some rudimentary exposure to Jewish tradition, without deep familiarity with its intricate details. When it came time to direct Paul Freeman to say “a short phrase in Hebrew,” Spielberg simply recalled some of the words he remembered from synagogue services and fed them to the actor.

Spielberg’s Jewish heritage influences the story in broader and more subtle ways, too.

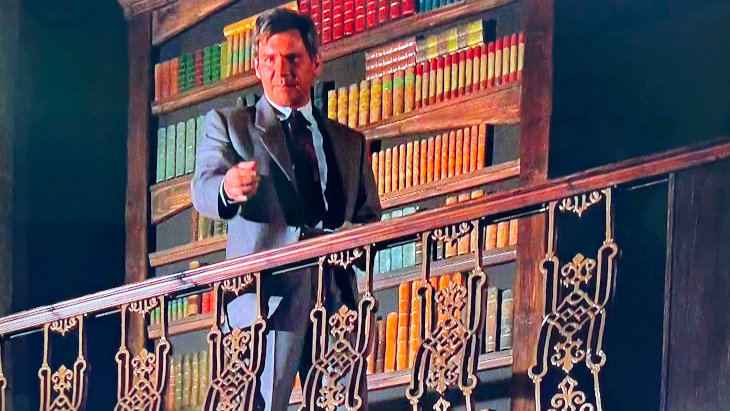

In the years after the Holocaust, higher academia was one of the fields where American Jews found the great success. Professors who were forced out of Europe, including luminaries like Albert Einstein, were able to re-establish themselves in the United States.

But in American popular culture, academics were rarely the heroes. Although Indiana Jones isn’t Jewish, the elevation of a professor to hero status is an expression of a uniquely Jewish American fantasy.

Professor Indiana Jones

Professor Indiana Jones

The Jewish American coding of Indiana Jones comes up in many ways throughout the series.

It wouldn’t have changed the story much to make Indiana Jones Jewish. So why did Spielberg, Lucas and Kasdan bury the character’s Jewishness in ‘code’ beneath the story surface?

In recent years, we’ve been blessed with a wave of Jewish-forward entertainment coming out of both Hollywood and Israel. Shows like “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel,” “Fauda,” “Shtisel,” and “Jewish Matchmaking” don’t shy away from putting Jewish characters in the spotlight. Even Spielberg’s own “The Fabelmans” is a story about his Jewish family. It’s easy to forget that just a few years ago, this kind of Jewish content was nearly impossible to find.

Jewish stories were seen as too small, too limited to reach a broad audience. They were perceived as too much of a risk. So when Spielberg made “Raiders,” he had to bury the Jewishness, to code it into the character and the story, so that the film could get made. He was able to use the Ark because it’s from a Biblical narrative that’s shared with Christianity and Islam; it’s not perceived as being exclusively Jewish.

It wasn’t until “Schindler’s List” in 1993 that Spielberg could make an overtly Jewish movie. He had to arrange for the financing himself since none of the studios would pay for it.

We’re fortunate to live in a time when Jewish stories are entering the mainstream. But we still haven’t seen an overtly Jewish hero like Indiana Jones.