Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

11 min read

How Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin created the first model of a yeshiva.

During the years I studied in yeshiva, friends and visitors were surprised by the striking spectacle of hundreds of pairs of learners sitting opposite each other, vigorously fighting over a page of the Talmud.

There’s a furrowed brow, a wrinkled forehead, a finger raised in triumph. Occasionally voices are raised in indignation, if not what appears as outright hostility.

Surrounded by books teeming everywhere, there is a hum of blended conversations, a cacophony of voices. But there’s also a tune; a sing-song cadence threading the animated arguments. The noise is deafening, overwhelming. It’s difficult to understand how anyone could actually be studying.

This fractious throng seems as far from a typical classical spiritual paradigm – the smiling Buddha sitting serenely under the lotus tree – as it’s possible to be.

It’s tempting to think the yeshiva has always just been there; that these same scenes have played out for centuries. Although the source texts have been poured over and picked apart for thousands of years, the yeshiva itself is a relatively modern construct.

It is the brainchild of a visionary Jewish leader. His name was Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin.

Born in the Lithuanian town of Volozhin (today part of Belarus), “Reb Chaim” as he is popularly known, was the foremost disciple of Rabbi Elijah Kramer, known as the Vilna Gaon, the genius of Vilna. That itself is enough to seal his place in Jewish history. In truth though, in terms of his historical influence, some argue that in certain respects Rabbi Chaim went on to surpass even his great teacher.

Legend has it that his father, the local bartender, divorced his mother within weeks of marriage.

Rabbi Chaim’s beginnings were inauspicious. That he came into this world at all was a minor miracle. Legend has it that his father, the local bartender, divorced his mother within weeks of marriage. The couple were only reconciled after a local Count (in a neat inversion of the typical bartender-patron dynamic) encountered the downcast and remorseful bartender, and intervened on his behalf. Reb Chaim was born shortly thereafter.

A Talmudic prodigy in his early 20s, Rabbi Chaim was introduced to the Vilna Gaon. He was already among the leading Torah scholars of his time. And yet, such was his veneration for the Gaon, that he began his Torah learning from scratch, incorporating his teacher’s penetrating analytical methodology. The focus was on ferreting out the meaning and intent of the sages of the Talmud and especially of the early commentators, with an emphasis on literal interpretation and on working from first principles.

Rabbi Elijah Kramer, the Vilna Gaon

Rabbi Elijah Kramer, the Vilna Gaon

Rabbi Chaim progressed quickly in this new approach under his new master, while also earning a highly respectable living as a cloth manufacturer. By 1773 at the tender age of 25, he was appointed head rabbi of Volozhin. He would hold the position until his death almost five decades later, albeit with a short-lived stint in between as head rabbi of neighboring Vilkomir for less than a year, where he angered the town’s leaders by refusing to accept a salary.

Rabbi Chaim continued to be influenced and awed by his great teacher. He made the pilgrimage to Vilna three or four times a year, where he would consult the Gaon on various questions on Torah and Jewish law he had collected in the interim.

On one such occasion, he posed to the Gaon a question of a different sort…

The Jewish world at the time was in a state of flux. The Enlightenment had by now reached Eastern Europe. Suddenly, a good Jewish boy had intellectual pursuits other than the Talmud to occupy his mind, if he so wished.

Torah learning was in decline for other reasons, too. Torah books were available only to the very well-off members of society. Often the town synagogue would lack even the basics of Jewish literature. Illiteracy was rife. Public Torah study was unheard of.

Torah learning was in decline and Reb Chaim had a vision.

It was in this context that Rabbi Chaim presented to the Vilna Gaon his idea for a central institution of higher learning that would raise the level of Torah study in the region, elevate its standing in the eyes of the public, and establish it as an intellectually compelling alternative to other academic pursuits.

Legend has it that Rabbi Chaim’s fervent pitch was met with his mentor’s firm disapproval. Only a few years later, when Rabbi Chaim again raised the issue – this time with far less conviction – did the Gaon give it his enthusiastic blessing. What had changed?

“The first time you asked me about it,” the Gaon explained, “too much of your ego was invested. You wanted to create it. It would not have succeeded. Now you talk about it more calmly, more critically, more rationally, with less of your personality and ego involved. It’s a great idea. Go ahead and do it!”

As a start, funds were needed. Rabbi Chaim delivered a rousing appeal to the community during the Ten Days of Repentance:

As representatives of the people, we are saddened to witness the Torah’s esteem diminishing from day to day. This is not due to sacrilege or rebellion. There are many who desire to learn, but they lack a piece of bread, while those who have it and want to study do not have teachers… The children of Israel are thirsty, their soul is longing for the holy books. We cannot refuse the pleading voices… I call on volunteers to teach and to finance. I will be the first volunteer, in heart and soul, to be among the teachers, and with God’s help, to maintain the students according to their needs… I ask you to join me in this sacred duty.

Nevertheless, contributions weren’t initially forthcoming. Eventually, Rabbi Chaim laid the cornerstone for the Yeshiva in 1803, six years after the death of the Vilna Gaon. He began with ten young pupils, whom he maintained at his own expense, with proceeds from the linen factory. It is said that his wife sold her jewelry to contribute to their upkeep.

Despite these humble beginnings, the yeshiva grew rapidly and its fame spread, which brought much-needed financial support. At its peak there were more than 400 students.

As much as Rabbi Chaim wanted Torah study to proliferate, access to his elite institution was by no means a fait accompli. Only the best and brightest were admitted. Applicants were asked to complete an extraordinarily demanding examination, requiring an in-depth and vast knowledge of the Talmud.

The Volozhin Yeshiva

The Volozhin Yeshiva

The yeshiva provided hearty meals, and each student received full room and board, and was clothed and cared for in every respect. Rabbi Chaim was adamant that nothing come between them and their learning; that no material concern should play on their mind while they were immersed in the intricate commentaries of the Talmud or a particularly knotty dialectic in one of the 63 voluminous tractates of the Talmud.

Indeed, one well-known anecdote is that every winter morning, before sunrise, Rabbi Chaim would don a pair of heavy peasant boots and rake the snow in front of the yeshiva entrance to clear a path for his students. There are many such tales.

In general, Rabbi Chaim’s pedagogical approach was unique and progressive; he regarded the intellectual autonomy of the student as sacrosanct. He understood that the personality of each student was something valuable, to be preserved, and helped them nurture independent thought and critical analysis.1 He addressed them as equals, and would often consult them for their perspectives on life and on learning.

His regard for his students was deep and sincere; he rejoiced in their celebrations and suffered in their pain. The students, in turn, revered their teacher, just as he had revered his, and responded in kind. Their devotion to Torah study knew no limits. They learnt, on average 18 hours a day. Some particularly diligent students would maintain a cycle of learning for 36 hours then sleeping for eight.

One inviolable principle of the yeshiva was that there had to be, at all times, at least one person learning Torah. Day and night the study hall was occupied. On occasions where that principle was in danger of being broken (such as the afternoon before the onset of Jewish festivals or Yom Kippur or straight after the fast), Rabbi Chaim himself would fill the breach.

Volozhin yeshiva ran in accordance with a very particular blueprint for Torah study. One of these was that Torah knowledge itself was not the most important thing; rather it was the labor, the intense strain, of the study; of “breaking one’s head” on the Talmud.

Another key principle was that Torah study was in its ideal form a social pursuit, to be done in pairs (and sometimes in groups) rather than as individuals. Hence the noise of hundreds of pairs of students learning out loud in a typical yeshiva study hall.

A third principle was that the sheer intellectual exhilaration of Torah study was its own reward, and indeed, the source of the deepest joy and of the most profound spiritual growth.2

Those principles have endured over centuries and today form the nucleus of the modern yeshiva. But back in 19th century Lithuania, as the Volozhin yeshiva grew in scale and influence, it drew the ire of the Russian empire who saw it, perhaps correctly, as a bastion against the regime’s objective of assimilating Jews into the greater population, and especially, of bringing them into the fold of the Russian Orthodox Church.

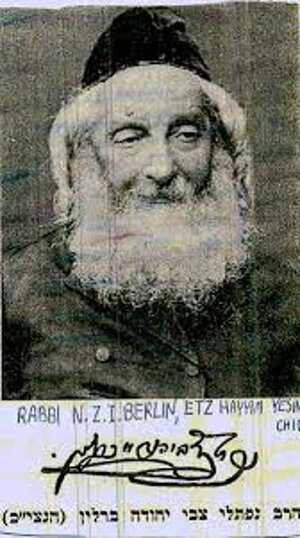

Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin

Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin

The pressure got so intense that in 1892, with Volozhin yeshiva in the hands of Reb Chaim’s distinguished son-in-law, Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (the Netziv), the yeshiva was forced to close. But unfortunately for the Russian government, the genie was already out the bottle and the Volozhin yeshiva’s closure led to a proliferation of similar institutions. In time, Volozhin became the forerunner of all the great Lithuanian yeshivas – Slobodka, Mir, Ponevezh, Kelm, Kletsk, and Telz – august academies of learning, many of which endure to this day, and which have spurred some of the great modern centres of learning in Israel.

Throughout his life, Rabbi Chaim wrote numerous halachic responsa (most of them tragically, lost in a fire in 1815). His magnum opus, however, is Nefesh Ha-Chaim (‘Living Soul’). A remarkable and suitably unique work, fusing kabbalah and Jewish ethics, it explores the nature of God and the deep secrets of the universe, but it also deals with less esoteric subjects such as the cultivation of good character, adherence to Jewish law, and of course, the primacy of Torah study. It is viewed as the Lithuanian response to Hasidism, though its criticisms are more subdued and less explicit than those of the Vilna Gaon.3 To this day, Nefesh Ha-Chaim remains a classic, a staple in the yeshiva world and beyond.

The 3,500 Jewish inhabitants of Volozhin were massacred in the Holocaust. Today, one striking remnant of the community still stands. An old yeshiva building. But beyond the building is what he built. The legacy of Rabbi Chaim lives on not just through the Torah he taught, but his approach to Torah he lived.

E. Leoni, Volozhin - the Book of the City and of the Etz Hayyim Yeshiva, Tel Aviv Publishing, 1970.

Hayyim Ben Isaac Of Volozhin, Solomon Schechter and Peter Wiernik, The Jewish Encyclopaedia.

Norman Lamm, Torah Lishmah – Torah for Torah's Sake: In the Works of Rabbi Hayyim of Volozhin and His Contemporaries, KTAV, 1989.