Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

Vampire Weekend's Surprising Jewish Stories

7 min read

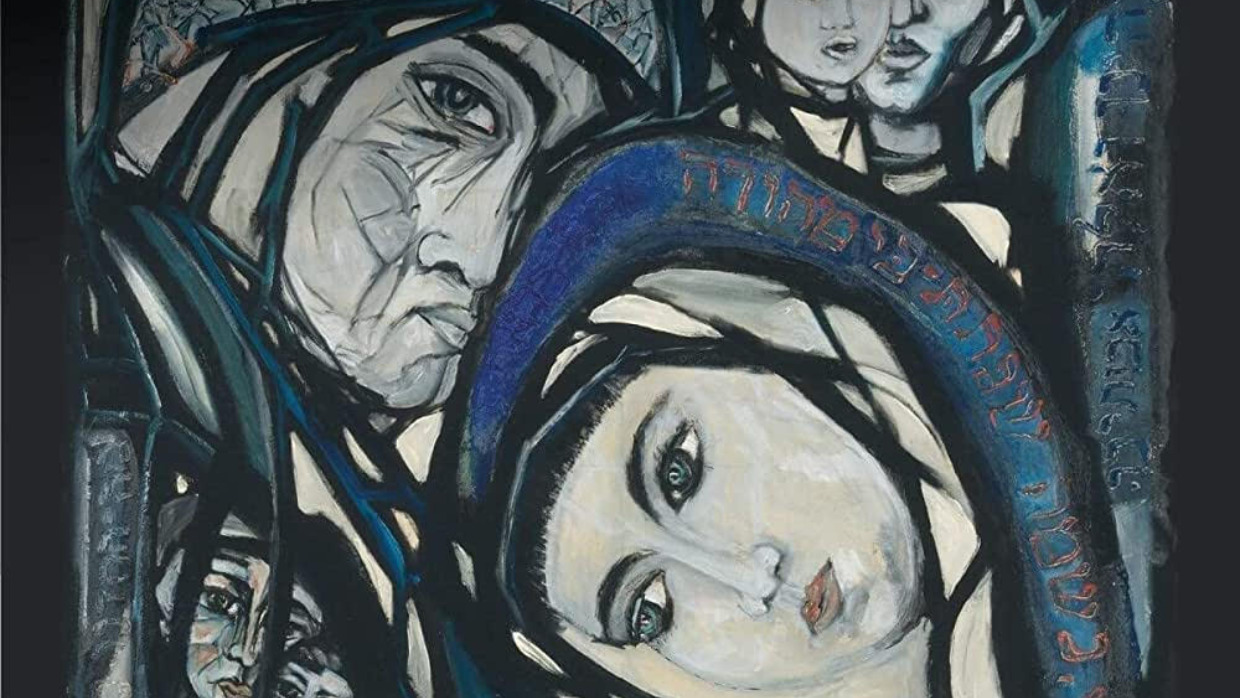

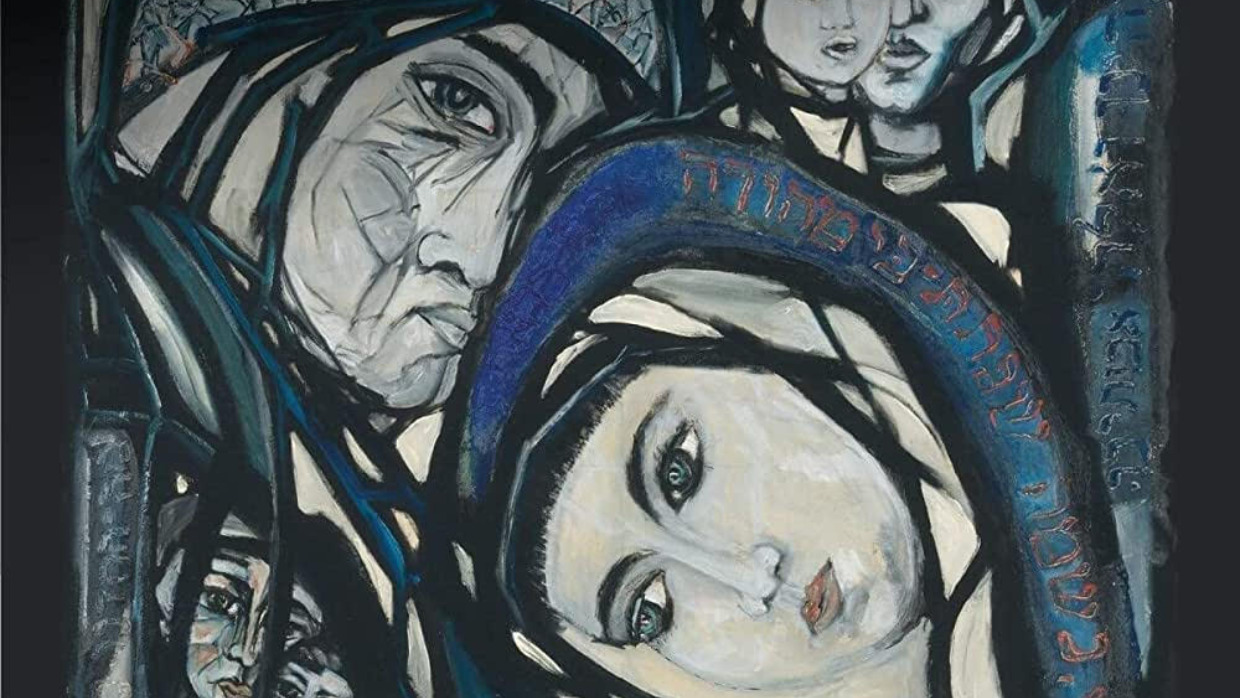

The album tells the real-life stories of Holocaust victims and is an unlikely global hit.

A new Yiddish album that tells the real-life stories of Holocaust victims is an unlikely global hit. Silent Tears: The Last Yiddish Tango by the Toronto-based Payadora Tango Ensemble is on top of the World Music Charts in Europe, and is educating a new generation about the Holocaust.

The album’s songs are woven out of harrowing survivor accounts, many of them collected by Dr. Paula David, a gerontologist in Toronto and one of the world’s foremost experts in caring for Holocaust survivors. In an Aish.com exclusive interview, Dr. David recalled her work with survivors which helped form the basis of some of the moving songs in Silent Tears.

“I moved back to Toronto in the 1990s,” Dr. David recalls, where she began working at Baycrest Center, a Jewish research and teaching hospital for the elderly. Dr. David worked with people experiencing dementia and noticed that aging Holocaust survivors were beginning to make up more and more of the adults needing care at Baycrest. As their memories of the present faded, in some cases their recollections of traumatic events in their youth began to come to the fore.

“We quickly realized not only were we unprepared for this unique group with new needs, but also there was no research on this,” Dr. David recalls. She began organizing Baycrest’s annual Holocaust Remembrance Day services and arranged regular weekly meetings for Holocaust survivors, most of them elderly women. They met in a room in Baycrest called the Terrace and eventually dubbed themselves “The Terrace Holocaust Survivors’ Group.”

At first none of the group members spoke about their experiences during the Holocaust. Dr. David would sometimes ask if there was any point in continuing meeting, and the survivors assured her that they valued their time together. “When I thought nothing was happening, so much was happening - they just weren’t talking.” She didn’t realize it at the time, but the survivors were protecting her. They didn’t want to tell this young, well-meaning social worker about the terrible experiences that had torn apart their lives.

Dr. Paula David

Dr. Paula David

One day, after about a year, a participant spoke about the Nazi Ghetto in which she and thousands other Jews had been imprisoned. She described how Nazis went through the Ghetto, grabbing Jewish babies and throwing them out of upper story windows.

“Oh, you were there?” a second survivor answered, explaining that she’d witnessed the very same atrocity.

“I felt sick,” Dr. David recollects, as she listened to the survivors in the group open up for the first time about their experiences. “They all started talking: my babies died then,” Dr. David remembers. Overcome with shock and grief, Dr. David couldn’t help but contrast these women’s experiences with her own life. “My babies were at home, waiting for me to make supper.”

After that, the survivors began to speak about their horrific experiences and they often marveled that they’d been able to endure. “One of the common things I heard over and over was ‘I never told someone this before’,” Dr. David says. The survivors realized they wanted more than anything to make sure future generations knew their stories.

“With permission, I taped the meetings,” Dr David explains. Dr. David began taking notes on different themes the survivors talked about and bringing them to the weekly gatherings. The focus of the sessions became editing the survivors’ stories, creating poems out of the memories they’d shared. It was a constructive, interactive way to discuss painful memories.

The group eventually moved onto to other creative projects, but Dr. David wanted to memorialize the beautiful poems they’d created together which were so full of the survivors’ precious and painful memories. Her teenaged son formatted the poems on a computer. Dr. David titled the collection The Collective Poems of the Terrace Holocaust Survivors’ Group and asked a bookbinder to print 1,000 copies. Employees of the printing company were so moved by the poems that they printed extra copies for each of the survivors.

Dr. David eventually left Baycrest, pursued her Ph.D., and became one of the world’s leading researchers working with aging Holocaust survivors. Yet four years ago, she found herself talking about The Collective Poems of the Terrace Holocaust Survivors’ Group once again.

It was 2019, and Dr. David helped organize a concert for a groundbreaking Yiddish album, Yiddish Glory, which brings to life songs written by Soviet Jews during World War II and was produced in Toronto. After the concert, Dr. David chatted with the album’s producer, Dan Rosenberg, and told him about work that she’d done years before at Baycrest, showing him the book.

“The poems dealt with subjects such as the pain of being unable to have children after being a victim of human experimentation, and the trauma of having to see a doctor decades later, after surviving from horrors at Auschwitz,” Mr. Rosenberg explained to Aish.com. He realized that the poems could be a powerful way to share the stories of the Holocaust with a wider audience. Dr. David has “been a pioneer in treating elderly victims of PTSD,” he observes. “One of the most important parts of her research that we wanted to share through music was to recognize the lifelong traumas children face decades later if they grow up during wartime.”

To bring Silent Tears to life, Dan Rosenberg turned to an award-winning team of musicians to create original songs out of Holocaust survivor testimonies. Three of the album’s songs are adapted from the survivors Dr. David worked with. Several others are based on the memoir Buried Words: The Diary of Molly Applebaum, written by survivor Molly Applebaum, who spent two years of her life, from 12 to 14 years old, buried with her cousin underground in a coffin-like box on a Polish farm, shielded by a Polish farmer who hid her from the Nazis.

Molly Appelbaum

Molly Appelbaum

Most of the songs are translated into Yiddish and set to music in the tradition of Yiddish tango, a genre that was widely popular in Poland before the Holocaust. (Two songs have been translated into Polish.) “In the 1930s, Warsaw was the capital of European tango, and most of the songwriters and composers of tango were Jewish,” explains Olga Avigail Mieleszczuk, a Polish born musician who converted to Judaism and has been described as the “queen of Yiddish tango,” and who collaborated on Silent Tears.

“This was a team effort,” Dan Rosenberg explains. “During the lockdowns, when we were all stuck at home in 2020, I was able to take a deep dive into the recordings of Jewish tango composers in Poland, and listened to hundreds of old 78s…to find melodies…. We worked with four brilliant lyricists, Vicky Ash-Shifriss and Aleksander Fisz, who live in Israel. They rewrote all of the Yiddish poems and lyrics as music while Olga Avigail Mieleszczuk and Malgorzata Lipska worked on the Polish lyrics.” Composer Rebekhah Wolkstein also composed music for some of the songs in the album.

The plaintive sounds of Yiddish tango convey the aching melancholy of the songs. For Dr. Paula David, the new album is a fitting tribute to the testimonies of Holocaust survivors she helped gather. It’s especially appropriate, she notes, that the songs are sung in Yiddish, the mother tongue of so many of the survivors she’s worked with.

With Silent Tears, “these women’s names and memories back,” Dr. David notes. “It’s so gratifying for me.” With the success of Silent Tears, “all kinds of people are listening and responding to it. To me, it’s an unexpected gift.”