Are Jews a Nation, a Family, or a Religious Community?

Are Jews a Nation, a Family, or a Religious Community?

7 min read

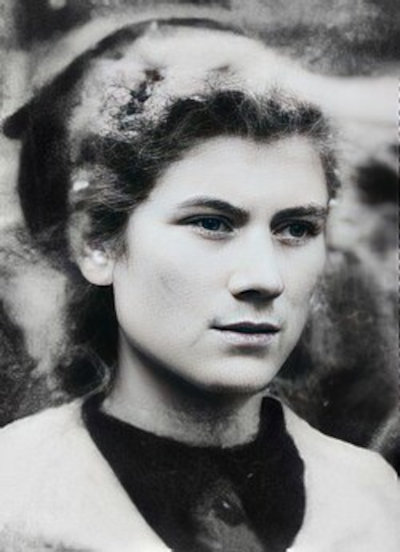

At 17, Masha Bruskina faced the Nazis’ noose with unflinching calm—her final act of defiance turned a warning into a timeless symbol of courage.

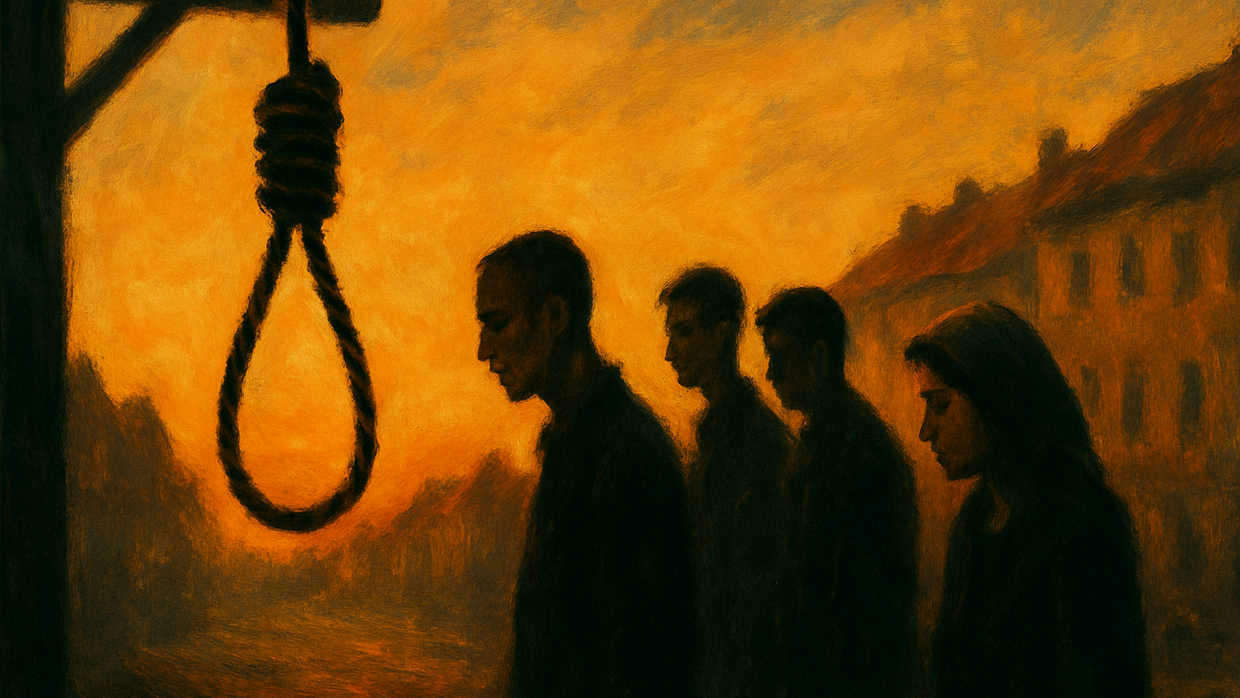

In October 1941, 17-year-old Masha Bruskina stood on a dusty street in Minsk, with a rope around her neck and a metal plaque pinned to her chest. The placard read in Russian and German: “We are partisans who shot at German soldiers.”

Even with death so near, she carried herself with startling calm. Witnesses later said the young girl refused to plead or flinch. In that moment, the Nazis treated her like a warning sign – yet Masha’s quiet strength became something else entirely. Her last wish, scribbled in a note to her mother in prison, was almost ordinary: “Don’t worry…nothing bad has happened to me…please send my green blouse and white socks. I want to be dressed decently when I leave here.”

Masha Bruskina holding the placard that read: “We are partisans who shot at German soldiers.”

Masha Bruskina holding the placard that read: “We are partisans who shot at German soldiers.”

This was no trained soldier or spy, just a 17-year-old math student and communist youth volunteer who risked her life by smuggling medicine, bringing clothes, and helping wounded Red Army soldiers escape the Minsk ghetto under the cover of civilian clothes.

When the Germans stormed Minsk in June 1941, life as its Jewish residents knew it ended overnight. Within weeks 80,000 people were crammed into a barbed-wire ghetto. Guards offered no food or medicine; families huddled in empty rooms, burning whatever they could find to stay warm.

Many Minsk Jews were shot on the spot or deported in cattle cars to death camps. By the fall of 1943 the ghetto was wiped out – nearly everyone killed or sent east. In that crucible, a surprisingly large number of Jews refused to accept that fate. In all, about 10,000 ghetto residents managed to flee to the forests and join partisan units.

This was possible because Minsk’s barrier was porous. Instead of brick walls, the Germans simply strung barbed wire, with roving guards. Jews crawled under fences at midnight, peeled off their yellow stars, and slipped into nearby woods or backstreets in the seconds the gaps allowed. Every day offered a choice: hide under a dirty blanket and pray for rescue, or dare to run for freedom.

By daylight Masha appeared to be an ordinary ghetto nurse. She volunteered at the large hospital in the old polytechnic institute building, a shabby place filled with wounded Soviet soldiers and sick prisoners. Nobody suspected that this gentle nurse was also a smuggler. In secret she used her hospital routine as cover to supply would-be escapees. To aid the underground, Masha supplied clothes and false documents to escaping Soviet officers. Hiding in plain sight, it helped that Nazi occupiers didn’t expect a teenage Jewish girl to be their enemy.

One resistance diary even tells of four Soviet officers she hid in garbage barrels on a truck. When the truck was flagged, a young Jewish courier named Tanya Lifshitz – part of the same underground network – helped the hidden men slip into the woods. They would later reach partisan brigades, thanks to Masha’s efforts.

Masha didn’t act alone. Friends in the ghetto and sympathetic Belarusians helped her move supplies and messages, and members.

Over six months, Masha’s skill grew. Every successful escape boosted her confidence. Once, a physician friend recalled, Masha calmly stitched up a wounded German sailor – while hiding a satchel of civilian clothes under her desk. After the sailor left, she sent a Soviet lieutenant wearing that sailor’s greatcoat toward the forest.

These operations often involved dozens of people – patients, nurses, even a sympathetic guard in one case who turned a blind eye.

Living a double life under Nazi rule was almost impossible to sustain. Eventually someone slipped.

Living a double life under Nazi rule was almost impossible to sustain. Eventually someone slipped. In mid-October 1941, Masha’s luck ran out. One of the Soviet soldiers she had nursed became terrified and told the German guards about the nurses smuggling prisoners. The next morning the Nazis raided the hospital. According to archive records, she was “betrayed by a patient” and arrested by German and auxiliary troops. Her comrades in the underground fled that night, scattering into hiding.

In the following days the Germans tortured Masha mercilessly, using electric shocks and beatings in an effort to crush her. But she held fast; Masha didn’t reveal any secrets under pressure.

Days before her execution, Masha managed to send a final note out to her mother. It was at once brave and tender: “Don’t worry… Nothing bad has happened to me. I swear you will have no further trouble because of me… please send my green blouse and white socks. I want to be dressed decently when I leave here.” She managed to sound calm, as if she were shielding her mother from the truth.

Facing torture and certain death, Masha refused to betray anyone else.

Facing torture and certain death, Masha refused to betray anyone else. Psychology research calls this moral courage: standing by your values under fear. When she was marched from her cell on October 26, she knew what was coming – and still she refused to beg or cry out. This final act of quiet defiance made clear that the human spirit can hold dignity even when all seems lost.

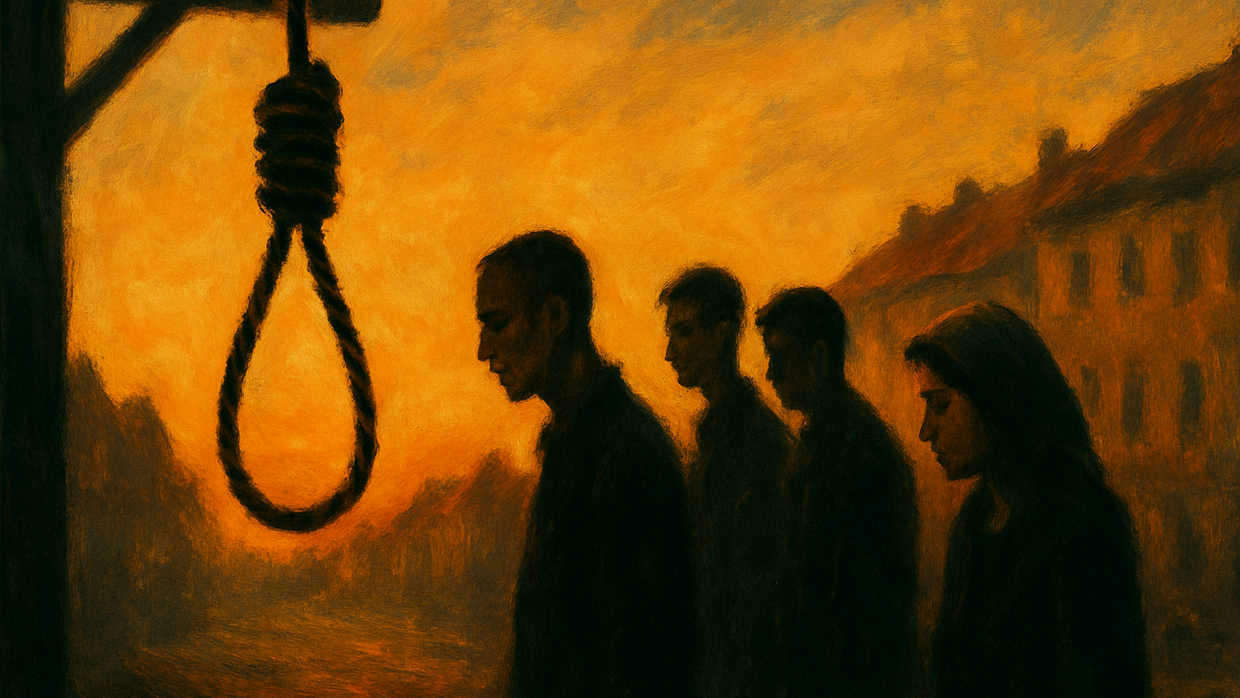

That October morning the Nazis turned the execution into a grisly public show. Masha was led, hands tied, down a grim factory street with two other partisans – a 16-year-old boy and an older communist leader. Civilians, mostly Jewish ghetto workers and townsfolk were forced to watch. As historian Mercedes Camino documents, the Germans “required to line the streets to witness the march to the scaffold and the execution itself.”

Soldiers manned the fence; one by one, victims were pushed onto stools against a wall. Each had a sign hung on their chest admitting a crime. Over Masha’s head the executioner pinned the board inscribed “We are partisans who shot German soldiers”. After the noose was fixed, the stool was cruelly kicked away. Some witnesses later said Masha turned her face away from the crowd, keeping her posture rigid.

The Nazis meant this macabre spectacle to terrorize onlookers into submission. Corpses were left hanging all day “as a lesson”. But German records admitted this kind of violence rarely worked as intended. By late 1941, documents show the occupiers noted that “this terror was neither an effective deterrent” to other resisters.

For decades after the war, Masha’s name was virtually lost. Soviet archives and monuments referred to her only as “the Unknown Girl.” As late as the 1960s and ’70s, textbooks told of “a girl” who died in Minsk, without giving a name. In fact, after Masha’s execution her own family was gone. Her mother disappeared in the destruction of Minsk’s ghetto just weeks later, so there was no one to champion Masha’s memory. The rock wall at the execution site in Minsk bore only the words “Unknown girl” for 68 years.

It took relentless detective work by survivors and historians to discover her identity.

It took relentless detective work by survivors and historians to discover her identity. Starting in the 1980s, researchers in Belarus and abroad combed through wartime archives and interviewed survivors of the Minsk ghetto. After decades of work, the breakthrough came in 2008, when Belarusian authorities officially confirmed that the young woman in the execution photographs was Maria Borisovna Bruskina. Within months, her initials and surname were added to the monument, finally removing the word “unknown.” In 2009, a proper memorial stone was placed at the site.

Masha Bruskina wasn’t physically stronger or older than her peers. What she had was the clarity and courage to make a moral choice.

Today, we may not face Nazi execution squads but each of us encounters our own moment of choice. It might be standing up to a bully, speaking out against antisemitism, or simply showing up for a stranger in need. The first step is deciding to do the right thing, despite your fears.

Masha showed that heroism can come from even from the smallest person in the room.

Spin this any way you want, but Masha was a communist activist who would’ve been horrified at being identified as a Jew.

A very brave young girl. Such extreme cunning and courage She demonstrated more courage than 95% of the idiot American college students that protest in the streets today.

This story has inspired and encouraged me What a hero she was, God bless her soul

An excellent example of heroism and courage in desperate times.

Such an impressive person. May her memory be a blessing and an inspiration.